You’ll Miss Sports Journalism When It’s Gone

The ranks of sports reporters are thinning—making it easier for athletes, owners, and leagues to conceal hard truths from the public.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

The new sports-media reality is troubling—and paradoxical. Sports fans are awash in more “content” than ever before. The sports-talk-podcast industry is booming; many professional athletes host their own shows. Netflix cranks out one gauzy, player-approved documentary series after another, and every armchair quarterback or would-be pundit has an opinion to share on social media. Yet despite all of this entertainment, all of these shows, and all of these hot takes, true sports-accountability journalism is disappearing.

Last month, after operating for years as a shell of its former self, Sports Illustrated announced mass layoffs that cast doubt on the magazine’s continued existence. And the problems go far deeper than SI’s well-documented issues. In 2023, The New York Times dissolved its sports desk, and the Los Angeles Times announced that it would no longer run day-to-day games coverage. More recently, the Los Angeles Times laid off several of its remaining sports reporters, and similar cutbacks have gutted sports coverage at smaller-market papers. Even ESPN, one of the last lions remaining, is not what it used to be. The media giant is reportedly in “advanced talks” to give the NFL an equity stake in its holdings, a decision that would raise serious questions about ESPN’s ability to cover America’s most popular sports league with journalistic impartiality.

Many sports reporters continue to do vital work, of course, with The Washington Post and The Athletic (owned by The New York Times) leading the way. But their ranks are thinning, making it easier for athletes, owners, and leagues to conceal hard truths from the public.

This is not just a problem for sports fans; it’s a problem for all of us. You may not care about sports, but sports cares about you. Its fingerprints are everywhere in American life: on entertainment, culture, politics, business. College-football coaches are among the highest-paid public-sector employees in the country. Team owners wield tremendous financial and political clout. Stadium deals can remake an urban landscape and drain a local tax base in the process. And now an entirely new industry has been erected on top of the existing one.

Legalized gambling—something that professional leagues once staunchly opposed—has unleashed a fearsome new torrent of cash upon the sports landscape. Americans wagered more than $100 billion last year on sports alone and are on pace to shatter that record in 2024. Meanwhile, the new name, image, and likeness rules at the college level have made the most talented NCAA athletes overnight millionaires. Bookies aren’t operating in the shadows anymore, and college boosters aren’t paying athletes under the table. But legalizing these activities only increases the potential for unethical behavior—and it’s all happening as fewer reporters are around to hold people accountable. In a time that demands watchdog journalism, many of the watchdogs are watching from the couch.

“The sports world is being turned on its head,” Craig Neff, a former longtime Sports Illustrated editor, told me. “But there’s no one there to ask: ‘Wait—how is this really working? Who’s beating the system?’”

At the peak of its power, in the 1970s and ’80s, Sports Illustrated was there to answer exactly these kinds of questions. Sandy Padwe, the investigations editor at the time, doesn’t remember ever seeing—or even discussing—a budget. “Nobody said anything about money,” Padwe told me. “We just said we need X amount of people to move, move, move, move—and do it. And the budget was there. I never knew what it was, believe it or not.”

This laissez-faire attitude, made possible by juicy ad revenues, meant that writers could go anywhere and do anything. They could stay on the road for weeks, or even months, and fly home transatlantic on the Concorde. But the trips weren’t just about over-the-top excess; they had a journalistic purpose. “You’d come across pieces that way,” Neff said. “There’s so much that you only find by being there.” Most newspapers dispatched writers to travel around the clock with the teams they covered. The longtime Boston Globe baseball writer Peter Gammons became so enmeshed with the Red Sox in the ’70s and ’80s, he told me, that he often shagged baseballs in the outfield during batting practice, when the team was on the road. This coziness could create its own problems; sportswriters sometimes protected the athletes they were assigned to cover. But it also led to the kinds of news tips, off-the-record conversations, and chance encounters that generated some of the industry’s most important scoops.

In 1985, Sports Illustrated published a 12-page investigation into how steroids were infiltrating American football. In a 1986 special report, the magazine revealed how bookies, mobsters, and gamblers operated in the shadows, just beyond the locker room. In 1987, it printed a first-person account of a college-basketball star who had won the national championship while playing high on cocaine—a drug that was consuming the sport, and the country, throughout the ’80s. In the fall of 1988, Sports Illustrated broke the story implicating a Canadian doctor in the steroid scandal involving the Olympic sprinter Ben Johnson. And just a few months later, the magazine received one of the most explosive tips in sports history.

The call, from a former bodybuilder in Cincinnati, came into the switchboard sometime in early 1989, on a Tuesday or Wednesday—the magazine’s off days—and through an unlikely chain of events made its way to a staff writer named Robert Sullivan, who was at home in his Greenwich Village apartment. Sullivan stopped what he was doing, picked up the phone, and placed a long-distance call to Cincinnati.

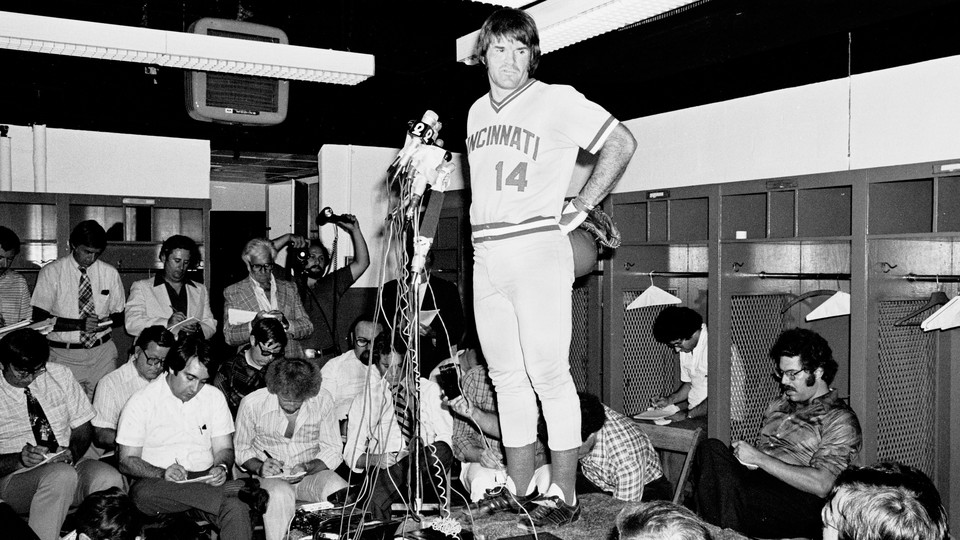

The tipster told Sullivan that Pete Rose—the manager of the Cincinnati Reds, baseball’s all-time hit leader, and one of the most important athletes of the 20th century—was consorting with bookies and gamblers and betting on baseball, including on Reds games, in direct violation of Major League Baseball rules. The details were hazy, but they were intriguing enough that Sports Illustrated sprang into action. Within days, Sullivan was on his way to Cincinnati, accompanied by a top editor, to start checking out the tip. Sandy Padwe, then the magazine’s investigations editor, quickly put more reporters on the story, until Sports Illustrated had an entire team of journalists across Ohio. And rumors about what the magazine was investigating soon drifted across town—to the offices of MLB, on Park Avenue.

Baseball had been generally aware for years of Rose’s gambling problems, as I learned while researching my forthcoming book about Rose’s rise and fall. At least once, according to my reporting, MLB officials even helped keep the matter quiet. But the specter of what Sports Illustrated might report about Rose’s gambling—and his potential bets on baseball—forced the league to do something. Upon learning of SI’s investigation, the outgoing commissioner, Peter Ueberroth; the incoming commissioner, Bart Giamatti; and Giamatti’s deputy commissioner, Fay Vincent, summoned Rose to New York for a secret meeting. Then, worried about what Sports Illustrated might dig up in Ohio, the three men decided to hire their own investigator to learn who was telling the truth: the tipster or the baseball legend Pete Rose.

“I don’t think we thought it was likely at all that Rose was dumb enough to bet on baseball,” Vincent told me during the reporting for my book. But they had to check it out, he recalled telling the others, “because we can’t be sitting here sucking our thumbs when Sports Illustrated says we have evidence that Pete Rose has been betting on baseball.”

Everything changed because sports journalists were on the story, doing their job. If Sullivan hadn’t taken the tipster’s call, if the magazine hadn’t sent him to Cincinnati, if the investigations editor hadn’t put more reporters on the story, the gambling allegations involving Pete Rose might not have surfaced in February 1989. They might never have surfaced at all.

The resources that Sports Illustrated threw at its Pete Rose investigation would be hard for most media outlets to find today. J. A. Adande—formerly of the Los Angeles Times and ESPN and now the director of sports journalism at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism—told me that sports reporters these days struggle to get face time with athletes. Many can’t even get into the locker room. The soft access that Adande and others once enjoyed is long gone. “You just don’t have that,” Adande said, “because people aren’t traveling with the teams.” And the few who do get only one chance to ask questions, in many cases: during the postgame press conference. Padwe, who left SI in 1994 and went on to teach sports journalism at Columbia University, told me that the players and teams have complete control. “I hear it from my former students all the time,” he said. “Complete, utter control.”

As a result, professional sports reporters are already missing stories. Last summer, student journalists at The Daily Northwestern—not sports writers at the Chicago Tribune or the Chicago Sun-Times—exposed a hazing scandal within the Northwestern football program. The grown-up journalists missed the story because they weren’t looking. They weren’t there, and they probably won’t be there next time, either.

Fay Vincent—who became the commissioner of baseball after Giamatti’s death, in 1989—wonders what story we might miss next, or what story we might be missing right now, as fans bet billions of dollars on games and athletes themselves sometimes struggle to resist the temptation.

“I think there’s a very high probability of more Pete Roses,” Vincent told me, “and there’s going to be more corruption.” He’s just not sure who’s going to be around to cover it.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Support for this project was provided by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.