Poland Shows That Autocracy Is Not Inevitable

The ruling party tried to use the Polish state to hold on to power, but voters rejected the effort.

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on curio

Thirty-four years ago, in June 1989, Poland woke up to a surprise. Despite a voting process rigged to favor the Communist Party, despite decades of propaganda supporting Communists and smearing anti-Communists, despite the regime’s control of the army, the police, and the secret police, the democratic opposition won, taking all of the seats that it was allowed to contest. A team of former dissidents took control of the government two months later—the first non-Communist government in Soviet-occupied Europe. In the decade that followed, Poland slowly decentralized the state and built a democracy.

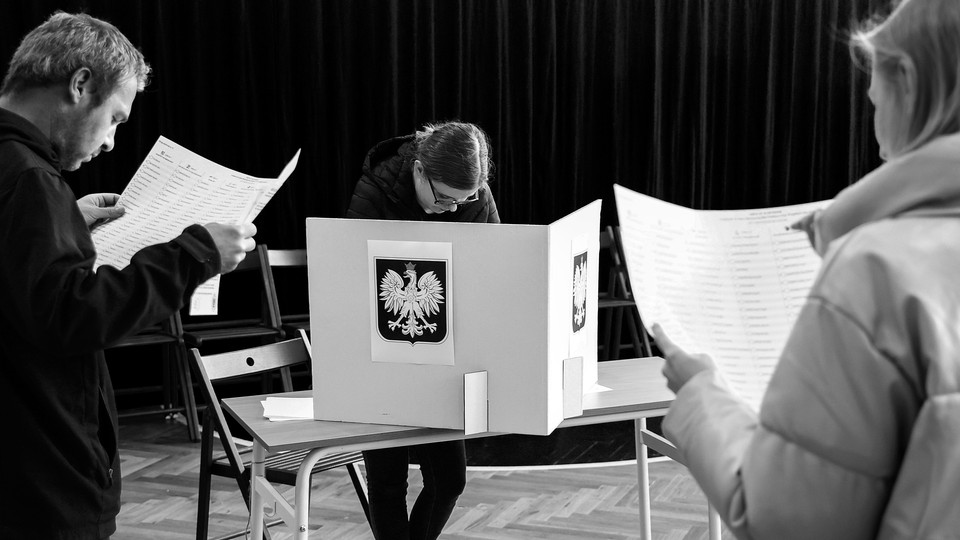

This morning, Poland woke up to a similar surprise. Since first winning power democratically in 2015, the nationalist-conservative party Law and Justice, or PiS, has turned state television into a propaganda tube, used state companies to fund its political campaigns, and politicized state administration. In the run-up to this election, it altered electoral laws and even leaked top-secret military documents, manipulating their contents for electoral gain. Even so, the party appears to have won only just over a third of the vote. Three opposition parties will likely have a parliamentary majority. Barring unexpected surprises, and perhaps some attempts to block their victory, they will form a center-right/center-left coalition. Once again, Poles will have to slowly decentralize the state and rebuild their democracy.

This election doesn’t mark the same kind of world-historical turning point. But like the one in 1989, it could represent an important shift. After democratic coalitions failed to defeat nationalist-conservative ruling parties in Hungary last year and in Turkey last May, and after elections in Israel brought a coalition of extremists to power, plenty of people feared that democratic change in Poland, too, was impossible. Against the odds, yesterday’s election has proved them wrong. Even if you don’t live in Poland, don’t care about Poland, and can’t find Poland on a map, take note: The victory of the Polish opposition proves that autocratic populism can be defeated, even after an unfair election. Nothing is inevitable about the rise of autocracy or the decline of democracy. Invest your time in political and civic organization if you want to create change, because sometimes it works.

As always when I write about Poland, I am declaring an interest: My husband, Radek Sikorski, is a politician for the largest opposition party, the Civic Coalition, and campaigned on its behalf, although he was not a candidate. Also, a dozen young campaign volunteers stayed at my house on Saturday night, and I concede that they might have helped convince me that campaigns aimed at mobilizing younger voters contributed to a record turnout.

Indeed, about 73 percent of Poles voted across the country, far more than the number that voted in 1989, and in some places the turnout was higher than 80 percent. In Warsaw, Gdansk, Lublin, and Wroclaw, as well as some European cities, voters stood in line for many hours, polling stations ran out of ballots, and some people were able to vote only long after the polls had been scheduled to close. At one Warsaw polling station near midnight, an election worker wept on live television, thanking her compatriots for showing up in such large numbers.

How did they do it? Anger is a powerful emotion, and over the past year, PiS made a lot of people angry. Repeated PiS corruption scandals—corruption being one of the inevitable results of politicized judges, police, and prosecutors—certainly helped the opposition. So did high inflation, partly created by PiS’s decision to spend heavily on social programs as the election approached. So did the decision by PKN Orlen, a state-owned oil company, to lower gasoline prices in advance of the vote, thereby causing shortages around the country, as well as general mockery.

But this turnout was produced by positive emotions too. Donald Tusk, the leader of the Civic Coalition, pointedly used the language of civic patriotism rather than angry nationalism. Thousands of volunteers came together to organize election-monitoring teams. Hundreds of thousands of people marched in two major demonstrations in Warsaw, carrying Polish and European Union flags; others joined a series of big public meetings around the country. The existence of three opposition parties meant that different messages were heard by different parts of the electorate, on the center-right as well as the center-left. Some of the candidates attacked PiS. Some used the language of unity and called for an end to polarization. The unexpectedly poor performance of a small, far-right, xenophobic party called Konfederacja may also mean that voters were attracted to the opposition’s unified support for Ukraine and for Ukrainian refugees.

Civic Coalition and both of the other two smaller democratic parties also went out of their way to ensure that women featured prominently in their campaigns, and that may have made a difference too, as did the opposition’s promise to end Poland’s harsh abortion restrictions. Pro-choice protest marches in 2020 and 2021—one was launched after a woman died of sepsis because doctors refused to end her doomed pregnancy—will have been, for many younger women, their first experience of politics. Exit polls show that women voted in larger numbers, and for opposition parties. Several young women candidates have had exceptionally good results.

Finally, the opposition offered Poles a return to the center of European politics, which is where the majority of them want to be. In this sense as well, the election is significant. If Tusk does lead a coalition government, Poland will cease to be in constant conflict with Brussels, Berlin, and Paris. In retrospect, the European Union’s controversial decision to oppose PiS’s assault on Polish democratic institutions was the right one: Future governments may remember it with appreciation. Although PiS built up an enormous reservoir of ill will, Poland might even once again start helping create European policies, not just oppose them.

None of this will happen overnight. Coalitions are notoriously hard to build and maintain, and there has been friction among the opposition party leaders before and during the campaign. A final PiS attempt to retain power cannot be excluded. PiS party officials have tried to buy off members of Parliament from other parties before, and they could try again. Even if that proves impossible, PiS will remain a large, hostile minority party. Its acolytes control all major state institutions. The president, also a PiS politician, has a lot of negative power, including the ability to veto legislation and block appointments. The unpicking of PiS’s efforts to co-opt and control the judiciary alone will be a legal and constitutional nightmare.

But the party isn’t the only issue. Millions of the party’s voters surely still believe what state television has been telling them: that Tusk is a German agent and the opposition are traitors. Convincing them otherwise will take a long, long time. All of these problems are difficult to solve—and all of them are better problems to have than those that Poland, and Europe, would have faced if PiS had won.