Will Tucker Carlson Become Alex Jones?

The host used his platform to bring hate and conspiracy theories from the fever swamps to cable TV.

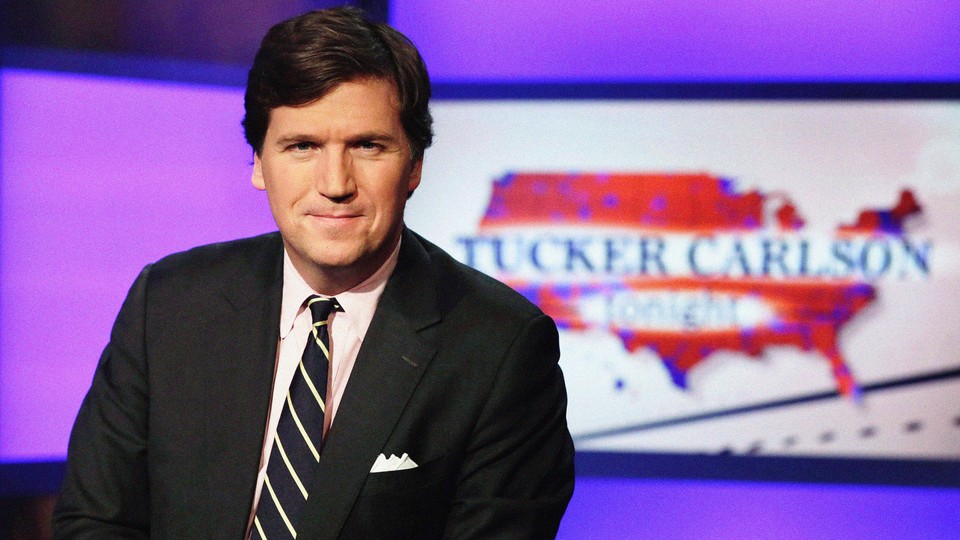

The final moments of Tucker Carlson’s last Fox News broadcast are perfect. His studio desk is strewn with pizza boxes. Across from him is the delivery man who’d traveled from Pennsylvania to bring him his favorite slice: sausage and pineapple. “It is a disgusting order, but I have no shame,” Carlson says with this mouth full, grinning. He then turns to the camera to wrap the broadcast with one final lie—“We’ll be back on Monday”—and a plug for the Fox Nation docuseries Let Them Eat Bugs, which alleges that the environmental movement to eat insects is, somehow, part of a global conspiracy. That’s it: One of America’s most popular and influential cable news shows ends with its host sharing the frame with a massive bug dead on a plate.

It felt like this final, absurd moment was ripped straight from Infowars, the far-right conspiracy website founded by Alex Jones. The Infowars model revolves around constructing a durable, alternative reality based on grievance. It reduces the world to a battle between good and evil (the site’s tagline is “There’s a war on for your mind!”), using lies, conspiracy theories, and theatrics to incite fear in the audience while positioning the host as a noble crusader. And it relies on alternating between righteous indignation and a winking, farcical tone that helps obscure the show’s real political project: taking dangerous, hateful, and reality-defying ideologies from the fringe and projecting them into millions of households every weeknight.

Carlson’s show premiered just a few days after the 2016 elections, and was immediately focused on stoking a culture war. According to The New York Times, when his show was elevated to the 8 p.m. slot in 2017, the host had his producers begin looking for small, local news stories “that were sometimes ‘really weird’ and often inaccurate but tapped into viewers’ fears of a trampled-on American culture.” The decision to highlight niche stories—about refugees, petty crime, DACA recipients, college-campus activism, and companies going “woke”—night after night made viewers feel as if their way of life was under an unrelenting assault by mainstream media, the left, and big business. Carlson used such examples to construct a case for his audience in favor of the white-supremacist “Great Replacement” theory, much to the delight of the country’s most infamous bigots.

The Times described this tactic as creating “an apocalyptic worldview”—a strategy that few have perfected better than Jones. On his marathon daily broadcasts, Jones is famous for shuffling through mountains of printed-out news articles, cherry-picking random facts from local news stories—he was, for example, among the first media figures to campaign against drag-queen story hours—and either embellishing them or twisting them to fit into one of his long-running conspiracy theories. Similarly, the Infowars website is a hodgepodge of racist aggregated stories misrepresenting local reporting to trigger outrage. When the local news stories dried up, Jones sent his staffers out to manufacture controversies to stoke the apocalyptic flames for a hungry audience. In a tell-all essay, Joshua Owens, a former Infowars staffer who grew disillusioned with Jones’s lies, detailed the process of having to scramble to find controversies to report on and making news up when that failed.

I spoke with Owens last summer, and he recalled the first time Carlson came to Infowars’ offices. Carlson and Jones spent time watching old Infowars clips about 9/11, which Owens thought might have inspired Tucker Carlson Tonight: “If you ever watch clips of Tucker—which I try to avoid at all costs—you can see some of the mannerisms,” Owens said. “Like Jones, he is enough of a showman that he can be compelling to an audience that doesn’t have the information to rebut him.”

Carlson’s most vile conspiracy theories—about COVID vaccines, white replacement, and the notion that January 6 was a peaceful protest—are the most indelible examples of his Jones-ification. But just as important and insidious is the way that Carlson packaged his propaganda. Like Infowars, Carlson was frequently absurdist in a way that delighted his fans and trolled critics. He branched out from the one-hour cable-news format with a series of original programming on the streaming platform Fox Nation. With titles such as Blown Away: The People vs. Wind Power, The UFO Files, and Cattle Mutilations, these subscriber-only offerings appear nearly indistinguishable from the direct-to-video Infowars documentaries that Jones became famous for in his early-internet days. The most viral of Carlson’s originals was an episode called The End of Men, whose promo featured a nude man bathing his testicles in ultraviolet light while Also Sprach Zarathustra plays. (You might remember the song from the opening of 2001: A Space Odyssey.)

The promo, like some of Carlson’s original-series concepts, is ridiculous to the point of being funny—which is the point. As with Jones, who has screamed until his face turned red about chemicals that “turn the friggin’ frogs gay,” Carlson and his staff understood how to use absurdity to entertain while introducing extreme ideas to mainstream audiences. His team, which at one time included a head writer who resigned after being accused of posting racist and sexists messages online, seemed acutely aware that the nightly audience also included a handful of liberal media monitors who would aggregate and screenshot the worst bits of each show to share over social media. Carlson’s lower-third chyrons eventually seemed to acknowledge and troll this group directly:

I’ll always remember this classic…. #TuckerCarlsonOut #SexCrazedPandas #AllTuckeredOut pic.twitter.com/340dtKFUVL

— Wayne Harrison (@waynomac39) April 24, 2023

With this graphic and chyron on-screen, Tucker Carlson literally said: "How do we save this country before we become Rwanda?" pic.twitter.com/SlFDmAyOn0

— Justin Baragona (@justinbaragona) June 25, 2021

For the past few years, it’s been common to log on to Twitter in the evenings and see my timeline full of outraged screenshots and clips from the show, which amplified Carlson’s dangerous rhetoric even in seeking to decry it. As with Infowars, this brand of “earned media” only increased Carlson’s profile as a hero for the far right. (Jones, too, was a fan, and texted Carlson regularly, leaked court documents show.) It also cast Carlson as a formidable political villain and one of the most dangerous influences in right-wing media. By 2020, Carlson was enough of a polarizing figure to generate buzz as a potential 2024 presidential candidate, in no small part because of his ability to outrage the left.

The details of Carlson’s Fox departure are still murky—the company released a terse, vague statement—and it’s unclear whether a spate of lawsuits, including the recently settled proceedings with Dominion Voting Systems, played an outsize role in the abrupt split. Even less clear is what Carlson might do next: Although Carlson 2024 would add even more chaos and extreme rhetoric to an already nightmarish campaign season, it’s easy enough to imagine him starting yet another mask-off independent media organization and becoming even more brazen and radical with his content.

I messaged Owens this morning after the Carlson news broke to ask if he could see Carlson going full Infowars. “The show was essentially a duplicate of Jones’s already, at least in content,” he said. “I definitely agree that he brought that model to prime time.” Still, it seems unlikely that Carlson, who has spent his entire career palling around corporate media and among Beltway elite, would want to work on the fringes. Ultimately, he is most effective laundering extreme talking points in a suit and tie. “He’s always seemed to want to be an insider, masquerading as an outsider,” Owens argued. “Which I think is something he and Jones have in common.”

Carlson’s legacy will live on in a legion of angry and paranoid former viewers. But his centrality in our current politics—and all of the danger that represented—came from his platform. Up until this morning Carlson was a man who sat at the very top of a toxic information ecosystem, one that cycles fever-swamp, message-board garbage upward and outward. At least for a moment, the cycle is broken. Carlson’s megaphone is gone, along with a captive audience. Stripped of his time slot, Carlson has lost the last, thin veneer of credibility separating him from the conspiracy theorist he’s been aping. Tonight, the only difference between Alex Jones and Tucker Carlson is that one of them has a show.