Everything Is About the Housing Market

High urban rents make life worse for everyone in countless ways.

I have a gripe about San Francisco: The bagel stores open too late.

My neighborhood, Bernal Heights, has a number of excellent purveyors. The tasty BagelMacher opens at 8:30 a.m. on the weekends, at which point my sons have been up shrieking and destroying things for three hours. Chicken Dog, which sells the best salt bagel I have had in California, opens at the downright brunch-ish hour of 9 a.m. I come from the Bagel Belt, to co-opt a term. In my mind, bagel shops open at 6 a.m. That’s standard. That’s how it works. You should be able to feel caffeinated and carb-loaded at 6:03 a.m. every day of the year, including Christmas. But not here in the Bay Area. And the housing shortage is to blame.

That’s my pet theory, at least. San Francisco has built just one home for every eight jobs it has added for the past decade-plus, and rents are higher here than they are pretty much anywhere else in the United States. The city could stand to increase its housing stock fivefold, according to one analysis. What does that have to do with bagels? Few people can afford to live here—and especially few families who have to bear child-care costs along with shelter costs. Thus, San Francisco has the smallest share of kids of any major American city. Meaning a modest share of parents. Meaning not a lot of people who might be up at 5:51 a.m. on a Sunday morning, ready to hit the bagel store.

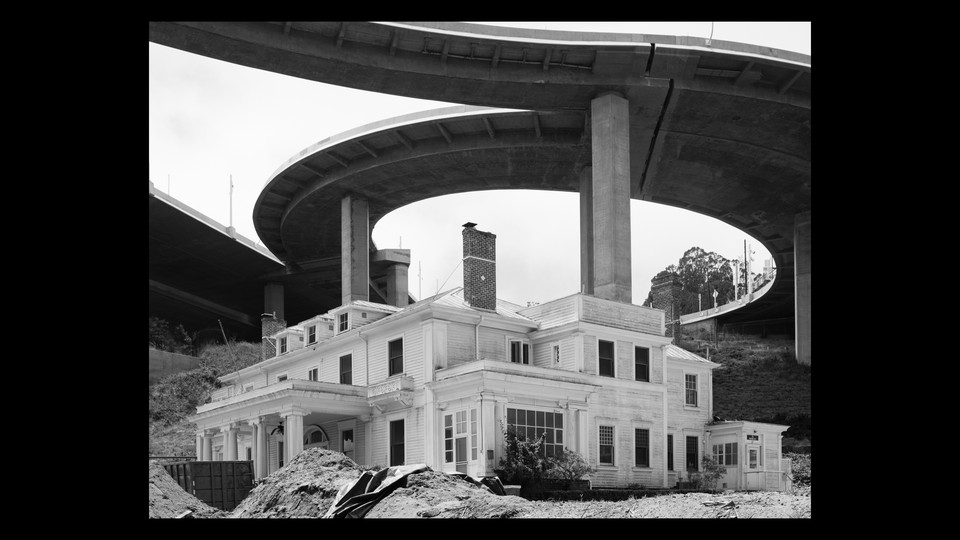

The late opening hours of San Francisco’s bagel joints are not the only things you can reasonably tie back to its housing crisis. The declining share of gay residents in its historic Castro neighborhood. The blanding of the city’s bohemian culture. Even the graying of its famous brightly painted Victorians. (Apparently, the people who can actually afford to buy homes in the city prefer understated colors.)

The crisis is not just happening in San Francisco. Housing costs are perverting just about every facet of American life, everywhere. What we eat, when we eat it, what music we listen to, what sports we play, how many friends we have, how often we see our extended families, where we go on vacation, how many children we bear, what kind of companies we found: All of it has gotten warped by the high cost of housing. Nowhere is immune, because big cities export their housing shortages to small cities, suburbs, and rural areas too.

Recently, a trio of analysts coined an apt term for this phenomenon: the housing theory of everything. You now hear it everywhere, at least if you’re the kind of person who goes to a lot of public-policy conferences or hangs out on econ Twitter. Writing in the journal Works in Progress, John Myers, Ben Southwood, and Sam Bowman took stock of many of the most pressing problems in the Western world, among them declining fertility, endemic chronic illness, brutal inequality, the climate catastrophe, sluggish productivity, and slow growth. They tied each of them back to the cost to rent an apartment.

High real-estate prices eat up young families’ budgets, prompting parents to have fewer kids than they would like. Building restrictions beget sprawl, spurring people to walk less and drive more, damaging their arteries and the planet’s climate. The inability of inventors to move to cities bursting with know-how and capital quashes a country’s long-term growth prospects; the inability of workers to move to cities with high wages dents its GDP. And driving up housing prices by restricting construction acts as a wealth transfer from renters to landowners. Indeed, housing prices might be the single biggest generator of financial disparities in many Western countries.

In a roundabout way, the French socialist economist Thomas Piketty inspired the term housing theory of everything. In 2013, the publication of Piketty’s opus, Capital in the 21st Century, sparked a broad debate about the causes and effects of economic inequality. “The book was a huge deal, and there was that Bloomberg Businessweek cover where Piketty was this heartthrob and everyone was obsessed with it,” Southwood, a British policy analyst and journalist, told me. When reading some work extending Piketty’s thesis, he told me, “I was thinking, Well, wait a second, land and housing really is an important part of this.”

Myers (a former hedge-fund portfolio manager and the co-founder of a U.K. YIMBY group) and Bowman (a think tanker) shared his housing obsession. Southwood and Bowman helped found Works in Progress, now supported by the fintech giant Stripe. And the three published their manifesto on the housing theory of everything a year and a half ago.

Post-publication, the idea took off online and in policy circles. Although Bowman, Myers, and Southwood focused on the most vital, sweeping effects of housing shortages and high housing costs, their theory has taken on a somewhat distinct meaning among its internet devotees. As a meme or a catchphrase, it applies to many of the crisis’s more obscure symptoms: riots in Liverpool, Canadian visa trends, the bribery of public officials, New Jersey moms’ desire for luxury bathtubs, and, in my case at least, bagel stores’ opening hours.

The theory is catchy because housing costs really do affect everything. They’re shaping art by preventing young painters, musicians, and poets from congregating in cities. How many styles akin to the Memphis blues and Seattle grunge are we missing out on? Would the Harlem Renaissance or the Belle Epoque happen today? They’re shaping higher education, turning elite urban colleges into real-estate conglomerates and barring low-income students from attending. They are preventing new businesses from getting off the ground and are killing mom-and-pops. They’re making people lonely and reactionary and sick and angry.

The answer is to build more homes in our most desirable places—granting more money, opportunity, entrepreneurial spark, health, togetherness, and tasty breakfast options to all of us.