The Autocrat Next Door

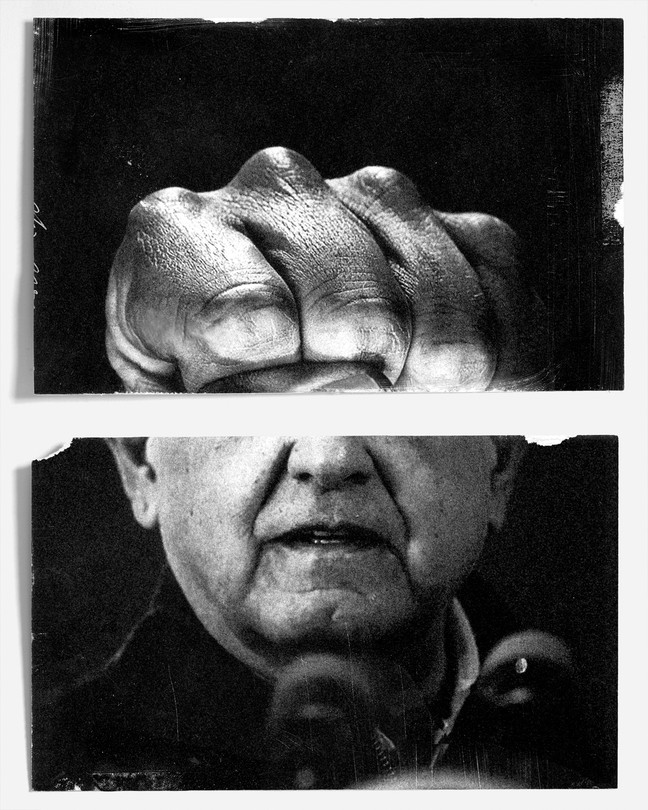

Liberal democracy in Mexico is under assault. Worse, the attacker is the country’s own president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Listen to this article

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

“In the past two years, democracies have become stronger, not weaker. Autocracies have grown weaker, not stronger.” So President Joe Biden declared in his 2023 State of the Union address. His proud words fall short of the truth in at least one place. Unfortunately, that place is right next door: Mexico.

Mexico’s erratic and authoritarian president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, is scheming to end the country’s quarter-century commitment to multiparty liberal democracy. He is subverting the institutions that have upheld Mexico’s democratic achievement—above all, the country’s admired and independent elections system. On López Obrador’s present trajectory, the Mexican federal elections scheduled for the summer of 2024 may be less than free and far from fair.

Mexico is already bloodied by disorder and violence. The country records more than 30,000 homicides a year, which is about triple the murder rate of the United States. Of those homicides, only about 2 percent are effectively prosecuted, according to a recent report from the Brookings Institution (in the U.S., roughly half of all murder cases are solved).

Americans talk a lot about “the border,” as if to wall themselves off from events on the other side. But Mexico and the United States are joined by geography and demography. People, products, and capital flow back and forth on a huge scale, in ways both legal and clandestine. Mexico exports car and machine parts at prices that keep North American manufacturing competitive. It also sends over people who build American homes, grow American food, and drive American trucks. America, in turn, exports farm products, finished goods, technology, and entertainment.

Each country also shares its troubles with the other. Drugs flow north because Americans buy them. Guns flow south because Americans sell them. If López Obrador succeeds in manipulating the next elections in his party’s favor, he will do more damage to the legitimacy of the Mexican government and open even more space for criminal cartels to assert their power.

We are already getting glimpses of what such a future might look like. Days before President Biden and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau arrived in Mexico City for a trilateral summit with López Obrador in early January, cartel criminals assaulted the Culiacán airport, one of the 10 largest in Mexico. They opened fire on military and civilian planes, some still in the air. Bullets pierced a civilian plane, wounding a passenger. The criminals also attacked targets in the city of Culiacán, the capital of the state of Sinaloa.

By the end of the day, a total of 10 soldiers were dead, along with 19 suspected cartel members. Another 52 police and soldiers were wounded, as were an undetermined number of civilians.

The violence was sparked when, earlier in the day, Mexican troops had arrested one of Mexico’s most-wanted men, Ovidio Guzmán López, the son of the notorious cartel boss known as “El Chapo.” The criminals apparently hoped that by shutting down the airport, they could prevent the authorities from flying Guzmán López out of the state—and ultimately causing him to face a U.S. arrest warrant.

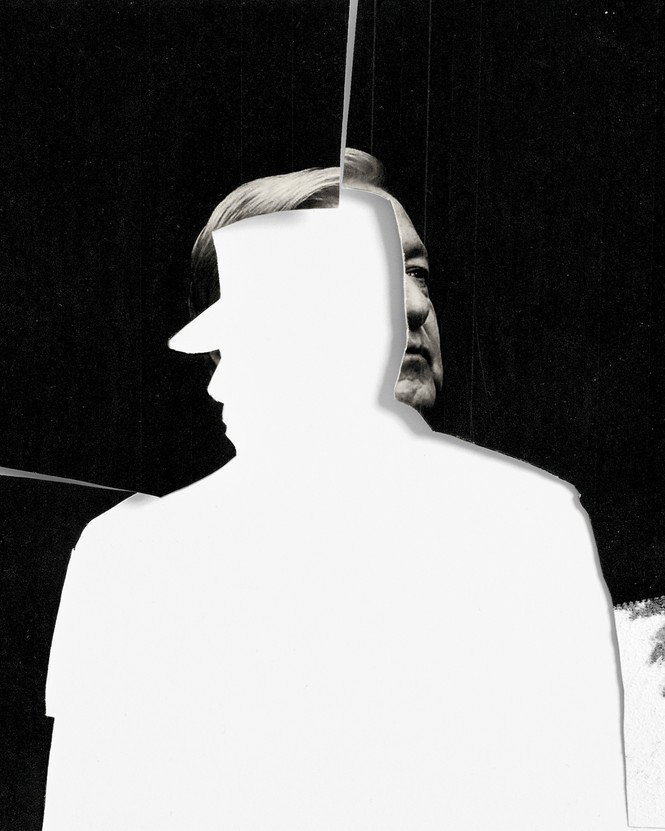

The criminals failed. But the point is: They dared to try. If the Mexican state decays further, the criminals will dare more.

Former President Donald Trump took a highly transactional approach to Mexico. If Mexico helped control illegal immigration and agreed to use fewer Chinese components in the autos it shipped north, Trump was happy to look the other way as López Obrador dismantled Mexican democratic institutions. López Obrador welcomed the deal. He restated his admiration for Trump just a couple of weeks ago: “I hold President Trump in high esteem because he was respectful to us … I can tell you that our relationship was good for the United States, for the American people. And it was very good for the people of Mexico.”

The Biden administration has asked rather more of López Obrador than Trump did—enough to irritate the Mexican president. Mostly, though, Biden has followed Trump’s line on Mexico. Perhaps the Biden administration has concluded that trying to uphold Mexican democracy and liberalism will be a waste of time, given how bleak the outlook is for both.

If things go very bad in Mexico, Americans will argue about whom to blame. The roots of the trouble can be traced back many years. But the warning alarm is sounding on Biden’s watch.

López Obrador is conventionally described as a “left-wing” leader. It’s certainly true that he proclaims himself an advocate of the poor and denounces the “fifís,” as he calls the denizens of Mexico City’s fancy neighborhoods. But it’s also true that he is an enthusiast of oil and gas development, and that he resisted the use of vaccines and masks against COVID-19.

In practice, any attempt to fit López Obrador into a left-right spectrum is futile and misleading. His project is to exploit grievances and discontents to consolidate personal power. Such leadership is common in our modern world. Americans have had some experience of the type themselves. North of the border, institutions and norms mostly checked a would-be autocrat. South of the border, the autocrat is so far prevailing. All North Americans should fear that the ultimate winner in Mexico will be autocracy—or even worse, chaos.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, often known by his initials, AMLO, was born in 1953 in the southern state of Tabasco to parents who kept a small shop. López Obrador acquired a college education and started a career in local politics. He climbed. In 2000, he won election as head of the government of Mexico City, a job with great visibility and power. Six years later, he mounted a campaign for president.

When the votes were tallied, López Obrador had lost by a margin of only about 240,000 votes out of roughly 40 million ballots cast. López Obrador refused to accept the result. Neither did he accept the multiple court rulings against him, nor the report of the European Union observers who found the election methods fair and accurate. He promised to produce proof of the fraud but never came up with anything convincing. When all else failed, his supporters proclaimed him president anyway. Summoned by López Obrador to protest, they blockaded streets and highways, disrupting traffic in and around Mexico City.

These methods appalled and frightened many liberal and democratic Mexicans. In 2006, the historian Enrique Krauze published a profile of López Obrador, “Tropical Messiah,” in which he wrote:

What is disturbing about López Obrador is not his social or economic program: Liberal opinion in Mexico can understand how a leftist democratic regime that is both responsible and modern could come to power. It is true that AMLO’s program turns its back on the realities of the globalized world and includes extravagant plans and unattainable goals, but it also contains innovative ideas that are socially necessary. No, what is worrisome about López Obrador is López Obrador himself.

López Obrador ran for president again in 2012. This time, the defeat was not close. He trailed by 3 million votes. His political career seemed finished. Yet, again, López Obrador did not accept defeat. He poured his energies into a new political movement, one built entirely around him: Morena—a complicated name that is both an acronym for the party’s formal name, the Movement for National Regeneration, and an invocation of Mexico’s protector, the dark-skinned Virgin of Guadalupe, who is sometimes nicknamed La Morena, meaning “the brown one.”

Like Trump in the United States, López Obrador was finally swept to power less by his personal appeal than by a broader crisis of the political system. His predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto, had advanced an ambitious reform agenda but rapidly lost his connection to Mexican voters. The handsome and well-dressed Peña Nieto came to personify the gulf between Mexico’s social and economic elites and its left-behinds.

Then, in September 2014, the Peña Nieto administration was shaken by scandal and horror: 43 young male students at a rural teachers’ college in the state of Guerrero went missing. Exactly what happened to them remains uncertain, but the widely accepted version of events is that local officials and police worked with criminal organizations to disrupt a planned protest meeting. The students were then murdered, either by the criminals or by the police.

The remains of only a few of these victims have been found and identified, but the search for them unearthed hundreds of other bodies in mass graves across the state. Resignations, arrests, accusations, and counteraccusations followed. Yet years of investigation failed to deliver satisfactory justice.

Disgust for the corrupt system spread through Mexican society. Electoral support for the established political parties collapsed. Suddenly, López Obrador’s Morena was the only organized political force still standing.

In July 2018, López Obrador won the most emphatic political victory in Mexico’s modern democratic history. He received 53 percent of the vote for president, 30 points more than the nearest runner-up. He also led his party to a two-thirds majority in the Chamber of Deputies, plus a working majority in the Mexican Senate and a majority of the state legislatures.

A man who, with scant regard for institutional checks and balances, wanted to base his power directly on the will of the people finally had his wish come true.

Twenty-two years ago, I stood on the south lawn of the White House as President George W. Bush welcomed to Washington another newly elected Mexican president, Vicente Fox. The moment was memorable. Over 200 years as an independent state, Mexico had been governed by emperors, dictators, and juntas. Through most of the 20th century, power in Mexico had been monopolized by a single ruling party. But in the election of 2000, for the first time in the nation’s history, executive power was peacefully transferred from one political party to another after a free and fair election.

This transition was enabled by one of the most remarkable institutions in Mexico: the independent, nonpartisan body that oversees elections, known since 2014 as the National Electoral Institute, or the INE. The INE and its precursors have compiled honest voting lists, enforced strict campaign-finance laws, impartially operated polling stations, and accurately tallied the results.

The INE implements complex rules at considerable expense. Each of those complexities is intended to correct an abuse bequeathed by the former one-party political monopoly. I met Lorenzo Córdova Vianello, the president of the INE’s governing council, at the INE’s Mexico City headquarters. He explained to me his institution’s purpose: “Most democratic electoral systems are based on trust. Mexico’s was built to inoculate [against] distrust.”

It was this agency that certified López Obrador’s defeat in the election of 2006. He has never forgiven it—and he is determined to reduce its sway.

Last October, López Obrador advanced a constitutional amendment to replace the INE’s nonpartisan leadership with people nominated by political parties and then elected by the public, who would choose among the party lists. Given the present disarray of the opposition, this proposal seemed likely to award Morena effective control of the voting system in time for the elections of 2024.

López Obrador’s constitutional proposal convulsed Mexican politics. On November 13, tens of thousands of Mexicans marched in the capital and other cities to protest. “So many things do not work in Mexico,” Córdova Vianello said. “But our elections do.” The constitutional gambit narrowly failed to pass in early December.

Undeterred, López Obrador tried another way. Instead of a constitutional amendment, he proposed an ordinary law. This law would leave the electoral institute’s leadership largely intact, but shrink the INE’s budget and reduce its local presence. Mexico has hundreds of voting locations. If the INE is disabled, the responsibility for operating them will likely fall upon local governments, most of them Morena-controlled. This Plan B has passed the Chamber of Deputies and awaits action by the Mexican Senate.

The seeming paradox of all this effort by López Obrador is that one of the enduring taboos in Mexican politics prohibits a president’s reelection after a single six-year term. Why try to manipulate an election in which he himself cannot be a candidate? Yet there is a logic here, a logic of power. López Obrador wants to ensure his succession by a completely loyal successor. By all accounts, he has identified just such a person: the serving mayor of Mexico City, Claudia Sheinbaum.

Sheinbaum would be the first woman president of Mexico and the first president of Jewish heritage. She is fiercely loyal to López Obrador. When I interviewed her in Mexico’s mayoral palace, she insisted that the election of 2006 had indeed been stolen from López Obrador. “People love López Obrador. Not everybody, but the majority of Mexican people,” she told me. “They love López Obrador, and they love what is happening in the country.”

The most reliably loyal successor, however, is not necessarily the most reliably electable. Sheinbaum lags in opinion polls behind other, more independent figures in Morena, possibly because, on her watch, a series of catastrophic subway accidents killed and injured dozens of passengers in Mexico City. Auditors blamed the accidents on poor maintenance.

López Obrador probably has the clout to impose his preferred choice on his party. But imposing that choice on the country is a greater challenge. The INE is an obstacle standing in the president’s way.

López Obrador is developing another tool of power, maybe the most ominous of all: a politicized military.

Over the past three decades, the United States has worked closely with Mexico to professionalize the Mexican military: to enhance its effectiveness, suppress corruption, and keep it out of politics. That progress has reversed under López Obrador. He has moved dozens of previously civilian functions into military control, creating new opportunities for astute generals and admirals to build personal wealth.

Potentially most significant, López Obrador has shifted control of Mexico’s customs collection from civilian agencies to the military. López Obrador justified the decision as an anti-corruption measure. Customs officials had “made a killing,” he said when he announced the move in May 2022. Now it is the armed forces that will be exposed to temptation instead.

Senior officers who succumb to temptation will need legal protection that can come from only one person: the president. López Obrador has shown his willingness to extend that protection. In October 2020, a retired general who had served as defense minister was arrested at Los Angeles International Airport on American charges of shielding drug traffickers. López Obrador personally intervened, threatening to review antidrug-cooperation agreements if the U.S. authorities proceeded to prosecute the general. The general was released. U.S. charges against him were dropped.

López Obrador’s supporters sometimes attribute his enthusiasm for military control to a naive faith in the integrity and competence of the armed forces. But naive people seldom rise to the top of Mexican politics. López Obrador’s expensive concessions to the armed forces look less like naivete and more like a president trying to build a power base of military officers who owe their illicit wealth to him—and over whom he holds knowledge of damaging secrets.

Yet even as López Obrador consolidates power in the presidency, that presidency presides over less and less of Mexico. The Washington Post reported in 2020 that an internal Mexican government document warned that the country’s criminal syndicates muster “a level of organization, firepower, and territorial control comparable to what armed political groups have had in other places.”

These criminal syndicates do a lot more than drug trafficking. They move illegal immigrants to, and across, the United States border. They steal and sell state-owned oil and electricity. They have entered the protection business on a huge scale. A retired American four-star general who has advised the Mexican military suggests that the syndicates should be considered a type of insurgency, a criminal one that functions in many parts of the country as an alternative government.

Where the insurgents prevail, they can contest—and defeat—the institutions of lawful government. In the 2021 midterm elections, dozens of state and local candidates were murdered. Others, including a former Olympic athlete, were kidnapped, and released only when they agreed to quit their races in favor of candidates more acceptable to the local criminal organizations.

López Obrador campaigned in 2018 on a promise to reduce violence by seeking an entente with Mexico’s criminals: “Abrazos, no balazos” was his slogan, or “Hugs, not bullets.” He made good on this slogan early on with some high-profile releases of wanted men. The same Guzmán López seized with such bloodshed in January had been captured before, in 2019, and that time López Obrador let him go, saying, “We do not want war.” Even after this second arrest near Culiacán, whether Guzmán López will ever be extradited to the United States remains very uncertain.

The relationship between the Mexican state and the criminal cartels is governed by rules and deals that are very difficult for outsiders to decode. What is discernible is that the arrangements are evolving in ways that indicate the criminals are gaining in strength and boldness.

In 2022, at least 13 Mexican journalists were killed, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Typically, the victims are provincial journalists who have offended some local crime boss. But in December, for the first time in many years, organized criminals attacked a prominent journalist in Mexico City itself.

Ciro Gómez Leyva is one of the most recognized journalists in Mexico. A 30-year fixture of television news, he hosts an evening program on Imagen Televisión, which is an upstart challenger to Mexico’s two dominant networks. On December 15, 2022, a motorcycle pulled up alongside Gómez Leyva’s Jeep Cherokee as he drove home after work. A gunman riding pillion opened fire, aiming shots at the journalist’s head. Fortunately, the SUV was heavily armored. The bullets cracked the windows but did not penetrate. Gómez Leyva maneuvered to evade the would-be assassins and raced to a friend’s home in a nearby gated community.

Only the day before the assassination attempt, Gómez Leyva had been a target of López Obrador’s vilification. At his daily media conference, the president had called Gómez Leyva a tumor on the brain of Mexican society. The day after the shooting, the president issued a condemnation of the attack. But days later, he mused that the attack may have been faked by somebody seeking to discredit the López Obrador administration.

I went to interview Gómez Leyva at the Imagen studios on January 11, shortly before he went on air with his evening news program. By coincidence, that happened to be the same day that the Mexican police had arrested 11 people in connection with the attack. Would justice be done? I asked. Gómez Leyva expressed doubt—and worse, fear that the attack might not be the last attempt on his life. “Maybe it was one time,” he said. “Maybe it will happen again. Maybe, maybe not. I don’t know. I have a lot of uncertainty.”

López Obrador describes his presidency as a whole new chapter in Mexican history—a “fourth transformation” of Mexican society comparable to the Mexican war for independence in the 1810s, the wars over the place of the Church in the 1850s and ’60s, and the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s. Because those first three transformations were convulsive bloodbaths, it’s a relief that the fourth is mostly oversold hype.

Despite his strong 2018 mandate, López Obrador has brought surprisingly little change to Mexican society. He has introduced a new universal old-age pension, a welcome addition to a social-security system that locks out nearly half of Mexican workers. But most of his political and economic capital has been committed to a handful of flashy megaprojects: a big new oil refinery in his home state of Tabasco, a tourist train that cuts through the Yucatán jungle, and—the flashiest of all—a new airport for Mexico City.

The airport project is especially revealing of López Obrador’s governance. The original Mexico City airport, which began service in the 1920s, is inadequate to modern needs. For years, Mexican governments have pondered a replacement. In 2014, under the Peña Nieto administration, a decision was at last reached. Land was assembled, contracts signed, and bonds issued.

López Obrador opposed the new airport as extravagant, unnecessary, and likely to enrich the wrong people. But by the time he took office, he inherited a done deal. The cost of abandoning the project would be nearly as great as that of completing it.

López Obrador was undaunted. He insisted that the penalties of cancellation would not be as great as the experts said. Besides, he had a site of his own in mind, a military air base to the north of Mexico City. True, it was much farther from the center city than the previous site. True, it had room for only two commercial runways instead of six. True, it was situated uncomfortably close to dangerous mountain ranges. But it would be his, so it was better.

The new airport opened in March 2022. Most travelers are unlikely to see it, however, because the only international routes it serves are to Venezuela, Panama, and the Dominican Republic. Add the money already expended on the first replacement airport, the fees payable on winding up canceled contracts, and the construction costs of the underused new airport, and López Obrador has spent something close to $20 billion to essentially reproduce Mexico’s dysfunctional status quo. (For comparison, the top-to-bottom renovation of New York City’s now-glittering LaGuardia Airport cost $8 billion.)

The other prestige projects are also failing. The oil refinery will cost twice as much as budgeted and is months behind schedule. The Yucatán train is likewise costing twice as much as projected, while inflicting serious cultural and environmental damage along its path.

Grandiose boondoggles do little to compensate for the reality of Mexico’s disappointing economic record. Had the Mexican economy grown only one-quarter as fast as China’s over the three decades after Mexico entered NAFTA in 1994, Mexico’s GDP per capita would by now have caught up to France’s and Italy’s.

Mexican growth faltered—spurring millions of Mexicans to seek better opportunities abroad, especially in the United States—and disillusioning those who remained behind. López Obrador blames Mexico’s underperformance on “neoliberalism.” Mexico, he argues, erred when it strayed from the proper path: a state-led economy protected against the outside world. Only a strong leader, untrammeled by rules and institutions, can restore the good old ways.

If López Obrador’s arguments sound like a promise to “make Mexico great again,” the echo of Trumpism is no coincidence. Lorena Becerra Mizuno, a pollster for the Reforma newspaper, described to me the core López Obrador voter: older, less educated, and more likely to be rural and male than the average Mexican citizen. Around the world, those uncomfortable in modernity have turned to authoritarian leaders who promise they can hold it at bay. But the promise is always false.

For all his denunciations of the Mexican elite, López Obrador has shown no will to tax them. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates that Mexico’s tax yield is 16.7 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, or about half of the OECD average.

López Obrador does not like to borrow either. His budgets run only modest deficits.

Instead, he has financed his new social ambitions by squeezing older ones, especially law enforcement, and health- and day-care services. To quote one credit-rating agency, “The government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has shown strong willingness to curb expenditure to maintain moderate deficits.”

The true source of Mexico’s troubles is that it did too little neoliberal reform, not too much. Much of the Mexican economy remains sheltered behind barriers that incubate monopolies and stifle productivity. Mexican labor law makes it almost impossible to fire workers at firms that pay taxes in the formal economy. As a result, many Mexican companies purposely stay small enough to escape into the untaxed and unregulated informal economy.

According to Luis Rubio, who heads the think tank México Evalúa, the Mexican governing and business elite have long preferred tinkering that preserves as much as possible of the status quo. In the small part of the economy opened up by NAFTA, manufacturing expanded, exports boomed, and growth soared. But only about 4 to 8 percent of Mexican urban workers are employed by firms directly engaged in NAFTA-related activities, estimates a new study by Santiago Levy, a former senior Mexican official now at the Brookings Institution. When the people who work in the efficient, modern NAFTA economy drive home, they still encounter an underpaid police officer who demands a bribe to spare them an arrest for driving through a stop sign that the police themselves have removed.

The true story of the so-called fourth transformation is big promises, little delivery. A president brought to power by disappointment with the status quo is perpetuating the status quo and feeding more disappointment. In only one way can López Obrador claim to be truly transformational—in his aspiration to suppress Mexico’s multiparty democracy and haul the country back to the authoritarian past.

“Poor Mexico: so far from God, so close to the United States” runs the saying commonly attributed to a bygone Mexican dictator, Porfirio Díaz. In the Trump years, Mexican feelings about the United States plunged to record chilliness, according to the Pew Research Center. Yet even as Mexicans headed to the polls in 2018 to elect the statist nationalist López Obrador, two-thirds of Mexicans continued to believe that NAFTA had been good for Mexico. Mindful of American abuses in the past, they have not given up on hope that the United States could be a source of good for Mexico in the future.

In the coming months, Mexican democracy will face severe tests. If Mexico can overcome them, a world of progress beckons. If not, the country risks sliding into authoritarianism at the center surrounded by anarchy in the hinterlands.

Mexican democrats are struggling to defend ideals. They do not ask much from Americans, but what they ask is vitally important to them: some assurance that they are not alone.