In late February 2022, the Russian artist Daria Serenko co-founded the Feminist Anti-War Resistance, an underground network of Russians protesting the invasion of Ukraine, publicizing Russian war crimes against Ukrainians, and helping Russian men evade conscription. In March, Serenko was forced to flee Russia for Georgia, where she wrote this prose poem.

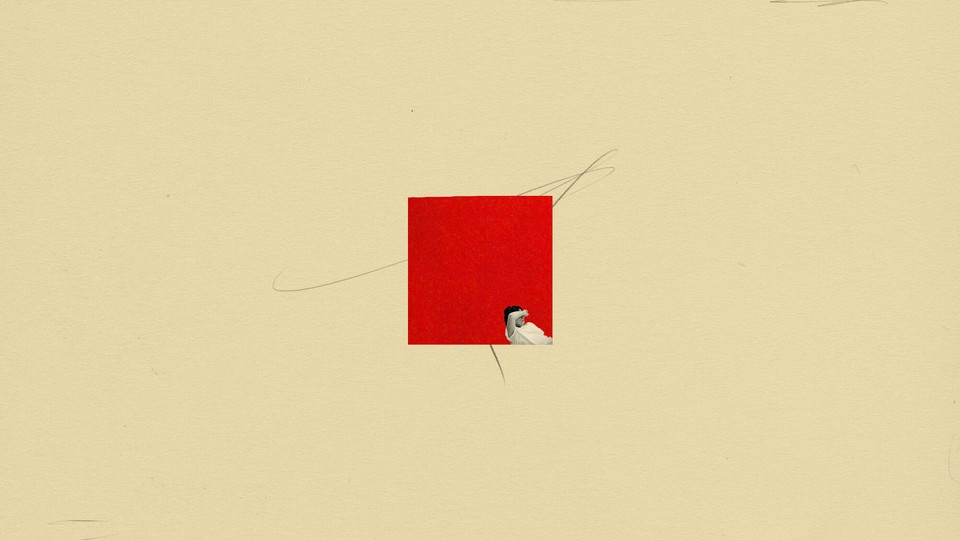

Yesterday a woman began giving birth directly on the Red Square with an assault rifle pressed to her temple. The guardians of law and order did not know what to do. Was it an act of unauthorized birth or an act of unauthorized protest? Parturition or performance?

Look at this woman with an unwelcome face whose waters broke on the Red Square. Here this woman is already screaming and writhing the way people were screaming and writhing at the last demonstrations; the woman is screaming the way people being tortured scream on the other side of the closed door at the police station. It’s nothing new for the cops. The woman is screaming and blood appears at the burst corners of her dry mouth. The opening of her mouth measures seven centimeters.

Time stands still and there’s no one on the square apart from the cops, the woman, and the daughter she is giving birth to, who is verbally camouflaged as a son. She told the police she was having a son so that they would act nicer to her. One of the cops, the good cop apparently, says: “You don’t worry, lady, you’re giving birth to a hero for us. Look at the time and place he picked to be born: in the very heart of Russia, at the very height of the war.” He is speaking really slowly for some reason, and the woman is also screaming slower and slower, and the ambulance isn’t coming. Every hour the clock strikes upon the Kremlin tower. Snowflakes melt even before touching the hot face of the woman in labor.

Gradually the cops calm down and even point their guns aside. They make repeated attempts to walk away from the scene in order to call for help but after a minute the road carries them back to where they started. The Red Square is where the Earth is at its roundest. Two policemen and a young woman find themselves completely alone on this round Earth in the very heart of Russia at the very height of the war.

“So we’ll be taking the delivery, right?” one of them asks into the air, giving the woman in labor a plaintive look, and extends his hand out toward her as if for a handshake. The woman in labor screams at him with all her force, swearing foully and loudly, and then bites through his hand with a long howl. With the same hand he slaps her across the face.

“You settled down now? You keep yourself together, lady. I don’t care if you’re a woman or not. If I have to, I’ll pull the baby out of you, and then stick you in the monkey house with the rest; you’ll be lying there whimpering on a filthy mattress.” The woman closes her eyes and nods. One cop props up her back; the other begins fidgeting between her legs.

An endless amount of time passes and, as the hour is striking upon the stately tower, they put the baby, wrapped in a police jacket and steaming in the nippy air, into her arms. The cops congratulate one another. There are tears in their eyes. They kiss each other on the cheeks, not even noticing they extracted a daughter rather than a son.

The woman with the girl in her arms is looking up at the clear, starry Kremlin sky. A memory steals into her mind that here, right next to her, an unburied dead man is lying in his Mausoleum. A rancid haze sometimes obscures her view: New crematoriums have sprung up across the country, and the smoke from their smokestacks sometimes casts a heavy smog over the city. The dead remind the townspeople of themselves by taking their breath away and forcing them to cough.

Time finally comes to life. Tourists and spectators start gaping around them. The men in uniform lift the mother and the daughter in their arms and carry them away. The woman is asked to wait for the doctors at the police station. She and the baby are carefully placed into a cage where other women are sitting, their heads bowed on one another’s shoulders. They show signs of having been there for many hours: Wet stains are spreading on their shirts and blouses. It’s milk. She decides not to ask them yet what they are there for. It’s quiet in the cell, except behind the iron lattice door, she can hear the whole bureau of police officers joyfully gathering to wash down the birth of her son.