The New Lost Cause

Republicans are holding up the January 6 insurrection—an effort to overthrow the American government—as the high-water mark of patriotism.

One of my favorite things about covering political rallies is that they typically start with a recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance. For anyone above school age, occasions to recite the pledge with a large group of people are irregular, and the ritual serves as a good reminder of what politics is about at its best, no matter how divisive what follows might be.

The pledge at a rally for the Republican gubernatorial candidate Glenn Youngkin in Virginia on Wednesday night was different. At the beginning of the event, which Steve Bannon hosted and Donald Trump phoned into, an emcee called an attendee up onstage and announced, “She’s carrying an American flag that was carried at the peaceful rally with Donald J. Trump on January 6.” Attendees then said the pledge while facing the flag. (Youngkin didn’t attend, and later tepidly criticized the moment.)

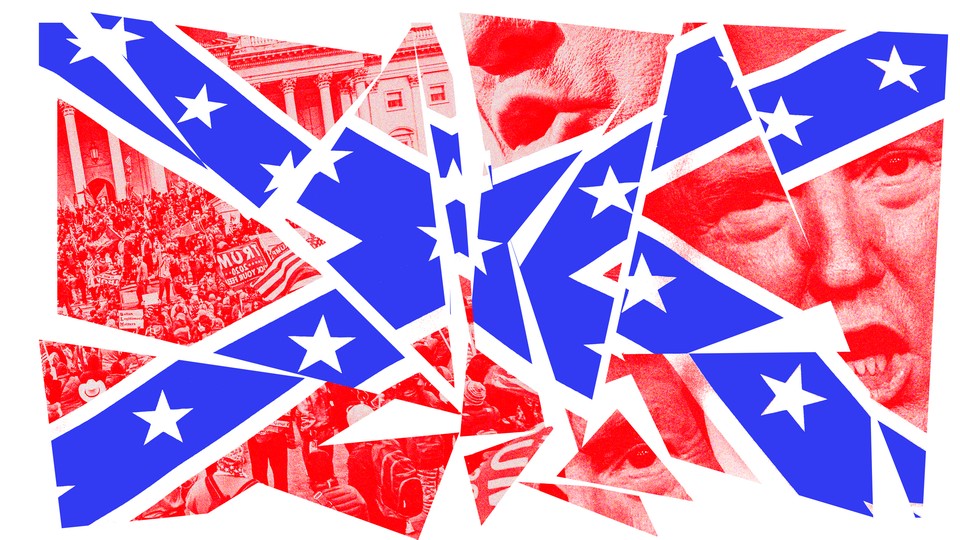

This is a bizarre subversion. The pledge affirms allegiance to the republic, indivisible and offering justice to all. This flag was carried at a rally that became an attack on the Constitution itself: an attempt to overthrow the government, divide the country, and effect extrajudicial punishment. Elevating this banner to a revered relic captures the troubling transformation of the events of January 6 into a myth—a New Lost Cause. This mythology has many of the trappings of its neo-Confederate predecessor, which Trump also employed for political gain: a martyr cult, claims of anti-liberty political persecution, and veneration of artifacts.

Most of all, the New Lost Cause, like the old one, seeks to convert a shameful catastrophe into a celebration of the valor and honor of the culprits and portray those who attacked the country as the true patriots. But lost causes have a pernicious tendency to be less lost than we might hope. Just as neo-Confederate revisionism shaped racial violence and oppression after the war, Trump’s New Lost Cause poses a continuing peril to the hope of “one Nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

In the immediate aftermath of the failed January 6 insurrection, Trump flailed in his efforts to interpret the day’s events. He praised the participants even as the riot was ongoing, saying, “Go home; we love you.” He insisted (despite ample video footage) that what had happened was a peaceful protest—some demonstrators were pacific, while many others were not—though he has also falsely claimed that antifa and Black Lives Matter had instigated a riot. He praised the protesters for courageously fighting back against what he insists, again falsely, was a stolen election, but also criticized police for using excessive force.

Out of this murk, a unified mythology has begun to form. Trump hasn’t so much resolved the contradictions as transcended them. To him and his movement, January 6 was a righteous attempt by brave patriots to take back an election stolen from them. The day’s events produced a martyr—Ashli Babbitt, an Air Force veteran shot and killed by a Capitol Police officer as she tried to enter the Speaker’s Lobby of the House. The rioters who remain imprisoned, meanwhile, are “political prisoners.” Now objects carried that day have become sacred too.

During his term as president, and especially during its last summer, Trump—though a lifetime New York City resident—celebrated the Confederate battle flag, praised Robert E. Lee’s generalship, and defended statues honoring Confederates. These statues were not erected immediately after the war. Rather, they first required the creation of the “Lost Cause” mythology late in the 19th century. As the law professor Michael Paradis wrote in The Atlantic,

the Lost Cause recast the Confederacy’s humiliating defeat in a treasonous war for slavery as the embodiment of the Framers’ true vision for America. Supporters pushed the ideas that the Civil War was not actually about slavery; that Robert E. Lee was a brilliant general, gentleman, and patriot; and that the Ku Klux Klan had rescued the heritage of the old South, what came to be known as “the southern way of life.”

Many of the monuments themselves were put up at times of conflict over civil rights for Black Americans. They took on a quasi-religious cast. At Washington and Lee University, where Lee served as president after the war, the chapel features a recumbent statue of the general where a church would typically have an altar. The building where General Stonewall Jackson was taken and died after being wounded at Chancellorsville was preserved, first by a local railroad and then by the National Park Service, and until 2019, was known as the “Stonewall Jackson Shrine.”

After Congress decided in 1905 to send back flags captured during the Civil War to their home states, Virginia placed the ones it received in a Richmond museum that, as Atlas Obscura describes, “began as a shrine to the Confederate cause, filled with memorabilia sourced from Confederate sympathizers.” To Lost Cause adherents, these flags were hallowed because they had been carried by the boys in gray as they bravely fought against Yankee aggression.

The paradigmatic moment for the Lost Cause myth is Pickett’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg, a bloody, hour-long Confederate onslaught later called “the high water mark of the rebellion.” As my colleague Yoni Appelbaum wrote in 2012, the label was unearned. The charge was a disaster, as was immediately clear to Lee, who told the survivors it was his fault. Its fate did not change the outcome of the war or even necessarily the Battle of Gettysburg. Though the assault was initially apotheosized by a pro-Union artwork, it was soon adopted by Lost Cause proponents as a moment of valor. “For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863,” William Faulkner wrote in 1948.

Like Pickett’s Charge, the January 6 insurrection was a disastrous error. It did nothing to prevent Congress from certifying Joe Biden’s election, and, in fact, several Republican members who had planned to object to the results decided against doing so after the riot. It got Trump impeached, a second time, and further tarnished his reputation, which hardly seemed possible.

Martyrdom is not necessarily nefarious, and some who die in battle do deserve veneration. Some heroes deserve veneration. Answering Stonewall Jackson, the Union had its own martyrs, such as Elmer Ellsworth. Ashli Babbitt’s death was awful. It was perhaps unnecessary for Lieutenant Michael Byrd to open fire, and it was certainly unnecessary for her to be in the Capitol that day, where she died in the name of lies that Trump and others had told her. As the journalist Zak Cheney-Rice writes, Trump’s aggrandizement of her death is rooted not in any genuine affection—he is largely incapable of caring about anyone but himself—but in opportunism.

The problem with these myths, the Lost Cause and the New Lost Cause, is that they emphasize the valor of the people involved while whitewashing what they were doing. The men who died in Pickett’s Charge might well have been brave, and they might well have been good fathers, brothers, and sons, but they died in service of a treasonous war to preserve the institution of slavery, and that is why their actions do not deserve celebration.

The January 6 insurrection was an attempt to subvert the Constitution and steal an election. Members of the crowd professed a desire to lynch the vice president and the speaker of the House, and they violently assaulted the seat of American government. They do not deserve celebration either.