Asymmetrical Conspiracism Is Hurting Democracy

In the past decade, conspiratorial thinking has shifted from a worrying factor in Republican politics to a defining feature.

As an American living in Britain for the past decade, I’ve had a front-row seat to two dysfunctional democracies hell-bent on embarrassing themselves. President Donald Trump warned that a hurricane was “one of the wettest we’ve ever seen, from the standpoint of water.” Prime Minister Liz Truss failed to outlast a lettuce at Downing Street. These years have not inspired confidence in democracy.

In Britain and the United States—and across most faltering Western democracies—this democratic dysfunction is routinely chalked up to a catchall culprit: polarization. The reason our democracies are decaying, we’re often told, is that we’re more divided than ever before. And that’s true: Polarization is worsening. Debates over Brexit and Trump tore citizenries—and families—apart.

But Britain’s and America’s democratic woes are not at all the same. The problems in American democracy are worse. That’s because a particularly insidious disease has infected the core of its political system, one that is not present to the same degree in other rich democracies: extreme conspiracism. Other countries, including the U.K., have polarization. America has irrational polarization, in which one political party has fallen under the spell of conspiratorial thinking. Polarization plus this conspiracist tendency risks turning run-of-the-mill democratic dysfunction into a democratic death spiral. The battle for American democracy will be a battle over reality.

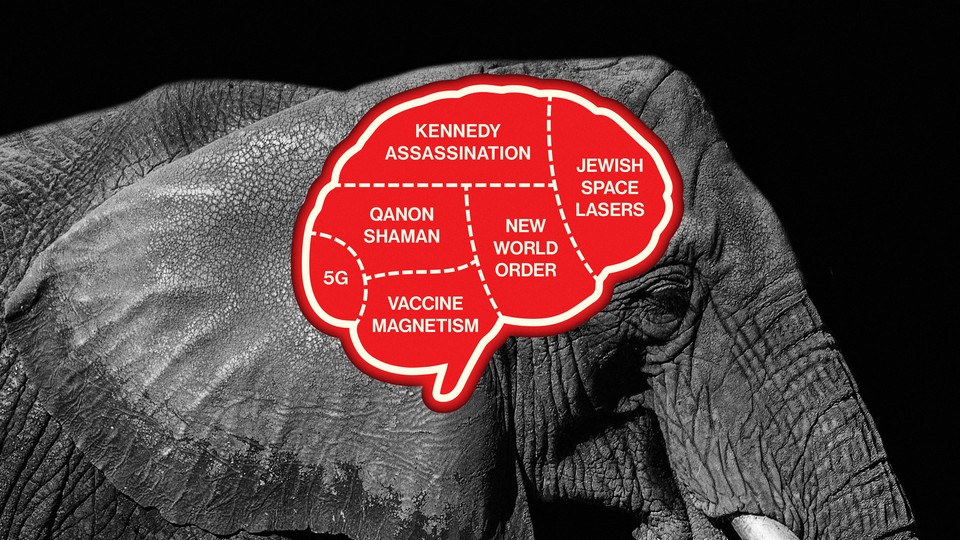

Within the modern GOP, conspiracy theories—about stolen elections, satanic cults, or “deep state” cover-ups—have replaced policy ideas as a rallying cry for Trump’s MAGA base. Trump’s disciples have developed an encyclopedic knowledge of a dizzying cast of characters, along with a series of code words for alleged cover-ups. They rattle off their accepted wisdom about conspiracies that most people have never heard of, such as “Italygate,” the absurd notion that the U.S. embassy in Rome, in conjunction with the Vatican, used satellites to rig the 2020 presidential election.

In Britain, far fewer people believe in conspiracy theories. According to YouGov polling, a third of Americans believe that a small group of people secretly runs the world, while just 18 percent believe the same in the United Kingdom. Similarly, 9 percent of Americans think COVID-19 is a fake disease. In Britain, that figure is just 3 percent. Seventeen percent of Americans agree with the statement that “a secret group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles has taken control of parts of the U.S. Government and mainstream U.S. media,” compared with 8 percent of Britons.

What’s really troubling about this political moment in America, though, is not merely the spread of conspiratorial thinking in the general population. It’s also that the delusions have infected the mainstream political leadership. The crackpots have come to Congress.

When Kevin McCarthy finally became speaker of the House this week, one of the first photos to circulate was a selfie taken with Republican Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, a former QAnon believer who once blamed a wildfire on Jewish space lasers.

Writing a similar sentence about modern British politics would be impossible. There’s just nothing like it. Instead, in Britain, conspiracy theorists are ostracized by the political establishment. Politicians may disagree about policy, but those who disagree about reality face real consequences.

Last week, for instance, Andrew Bridgen, a conservative member of the British Parliament, tweeted a graph from a conspiracy-theory website, spreading false information about the risks of COVID vaccines. The vaccination program, Bridgen wrote, was “the biggest crime against humanity since the Holocaust.” The response was swift. Bridgen was condemned across the political spectrum. His own party expelled him. The Tories, Britain’s ruling conservative political party, didn’t want to be associated with a conspiracy theorist.

Meanwhile, America’s political right is the leading global source of COVID conspiracy theories. The more outlandish, the better. Two years ago, in Ohio, in an almost exact parallel to Bridgen’s remarks, Republican State Representative Jennifer Gross compared mandatory vaccination to the Holocaust. Then Gross went much further. She effusively praised the testimony of a quack expert who claimed that vaccines magnetize people, such that spoons will stick to your forehead following a shot. “What an honor to have you here,” Gross fawned, after the alleged expert testified that vaccines can “interface” with 5G cell towers. Gross faced no primary challenger and was recently reelected, with 64 percent of the vote.

Rather than getting expelled from the Republican Party or becoming pariahs on the right, conspiracy theorists have become GOP stars. Mike Flynn, Donald Trump’s former national security adviser and a former top intelligence official, has falsely suggested that COVID-19 was created by George Soros, Bill Gates, and the World Health Organization to steal the 2020 election. In a separate statement, he argued that Yuval Noah Harari, the author of the best-selling book Sapiens, was part of a plot to alter human DNA and turn us into cyborgs.

Flynn should be an irrelevant laughingstock. Instead, he’s headlining right-wing conferences and commanding huge audiences. Flynn recently shared a stage at the deranged ReAwaken America event with Eric Trump—during which one speaker alleged that “demonic satellites” control voting in America. Donald Trump, America’s conspiracist in chief, spoke to the conference by phone.

Jonathan Gottschall, an expert on the links between evolution and human storytelling, has come up with a simple, compelling explanation for why people are innately drawn to conspiracy theories. We are, in his words, a storytelling animal. Our minds have evolved to latch on to stories to make sense of a maddeningly complex world.

Unfortunately, conspiracy theories are some of the best stories out there. They’re thrillers. Many would make great blockbuster films. And to debunk a conspiracy theory is to tell someone that there is no story. It’s trying to convince a person who has made sense of patterns—by squinting at them through the fun-house mirror of conspiratorial thinking—that those patterns are meaningless. That’s not a message the storytelling animal wants to hear.

All humans of all political persuasions are susceptible to conspiracy theories. Millions of Americans, on the political left and the political right, believe in them. But conspiratorial thinking is thriving especially on the right because it’s sanctioned, and endorsed, from above.

This asymmetrical conspiracism has been going on for a while now. The historian Richard Hofstadter noted how “the paranoid style” took root on the right in the mid-20th century, starting with McCarthyism and continuing through Barry Goldwater’s rise in 1964, shortly after John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

In the past decade, conspiratorial thinking has shifted from a worrying factor in Republican politics to a defining feature. This is partly because of Trump himself, who peddled countless debunked conspiracy theories, including that climate change is a hoax invented by China, and the lie that Ted Cruz’s father had links to the JFK assassination. As Trump took over the party, his conspiratorial lies became Republican orthodoxy. And that opened the door to conspiratorial influencers, who started inventing new lies.

Deranged grifters profit from what the writer Kurt Andersen has called the “fantasy-industrial complex,” in which media provocateurs, including Infowars and Fox News, have cashed in on political messaging defined by a conspiratorial mindset.

They prey on susceptible individuals, particularly those who are lonely and bored, browsing alone, and finding online communities to replace real-world ones. People with paranoid personalities are particularly vulnerable, as are those with a Manichaean worldview—a perception that the entire world is a battle between good and evil. At the ReAwaken America event, one speaker advanced the outlandish claim that the election was stolen by demons.

Alone, polarization is damaging but manageable. When polarization merges with deranged conspiracy theories, then democratic breakdown becomes far more likely. One purpose of democratic government is to allow citizens to solve problems through compromise without resorting to violence. Modern Republican conspiracist politics undermines those aspects—solving problems, compromising, and avoiding violence.

To solve a problem, you first must agree it exists. Democracy therefore requires a shared sense of reality. Instead, America has splintered into a choose-your-own-reality society, in which citizens self-select into whatever version of the world they want to inhabit, reflected back at them by media outlets that earn most when they challenge worldviews least. Conversely, in Britain, the BBC continues to dominate broadcast-media market share, and outlets that push conspiracy theories have tiny audiences. Moreover, left-wing and right-wing politicians both watch and agree to be interviewed by the BBC, whereas in the U.S., politicians gravitate toward friendly partisan media outlets.

Even if politicians can agree a problem exists, the Manichaean nature of conspiracy theories—and the extreme claims embedded in conspiratorial cults such as QAnon—makes compromise unlikely. Trying to find shared ground with a fellow American who disagrees with you on health care or taxes is one thing, but if you believe that Democrats are harvesting children to suck their blood, then working together on, say, democratic reform becomes much harder. Granted, elected Republicans on the whole don’t truly believe those more outlandish claims, but some of their core voters do, and that puts pressure on them to treat Democrats like evil enemies rather than legitimate political opponents.

On January 6, 2021, thousands of deluded insurrectionists attacked the Capitol because of lies spread by Trump and his acolytes. But the bigger problem was inside the ranks of Congress itself, as most House Republicans voted not to certify the election based on those debunked theories. These were the conspiratorial insurrectionists in suits—and they’re now in charge of the House of Representatives. What will they do now that they’re in power? Launch countless investigations into COVID vaccines, deep-state cover-ups, and the elections that they wrongly claim were stolen. Governing will be put on hold for two years.

Until modern Republican politics stops systematically empowering crackpots, America’s democratic dysfunction cannot be considered equivalent to the mere polarization that exists in peer countries such as Britain. In Britain, the political system is broken in ways that are more easily fixed. When reality shifts, people change their minds—and someone as incompetent as Liz Truss gets booted from office in just 42 days.

Unfortunately, loosening the grip of conspiratorial thinking in politics is extremely difficult; it means trying to make the storytelling animal give up on one hell of a story. But here is one nugget of wisdom for how to start, drawn from H. L. Mencken: “The way to deal with superstition,” he wrote, “is not to be polite to it, but to tackle it with all arms, and so rout it, cripple it, and make it forever infamous and ridiculous.”

QAnon is crazy. The notion that vaccines cause spoons to stick to you is moronic. Anyone who tells you that a best-selling historian is part of a secret plot to turn you into a cyborg is, with insincere apologies to Mike Flynn, a complete idiot. In the battle for reality, ridicule is a powerful weapon.