She Never Meant to Write a Memoir

Janet Malcolm’s autobiography presents an argument about the fundamental murkiness of autobiography itself.

Janet Malcolm once emailed to tell me she found an introduction I had written for my book on writers’ deaths, which included my own thoughts on a childhood illness, to be “surprising” but “powerful.” I understood this to be her diplomatic way of referring to the possibly showy or undignified decision to put myself into a book that was otherwise a work of biography and journalism. I think she was telling me she was surprised that she liked it. I was also surprised, given that she had communicated to me, in a thousand direct and indirect ways, her deep suspicion of autobiographical writing.

Any whiff of vanity, of self-satisfaction, of unchecked exhibitionism, was distasteful to her. She once wrote that the memoirist “must sustain, in spite of all evidence of the contrary, the illusion of his preternatural extraordinariness.” And Malcolm, who truly was extraordinary, was not comfortable with even the faintest hint of that presumption. Having made a career brilliantly puncturing the personal mythologies and blooming self-delusions of others, she felt compelled to be fiercely critical of her own. She had a horror of writing what she called a “puff piece” about herself.

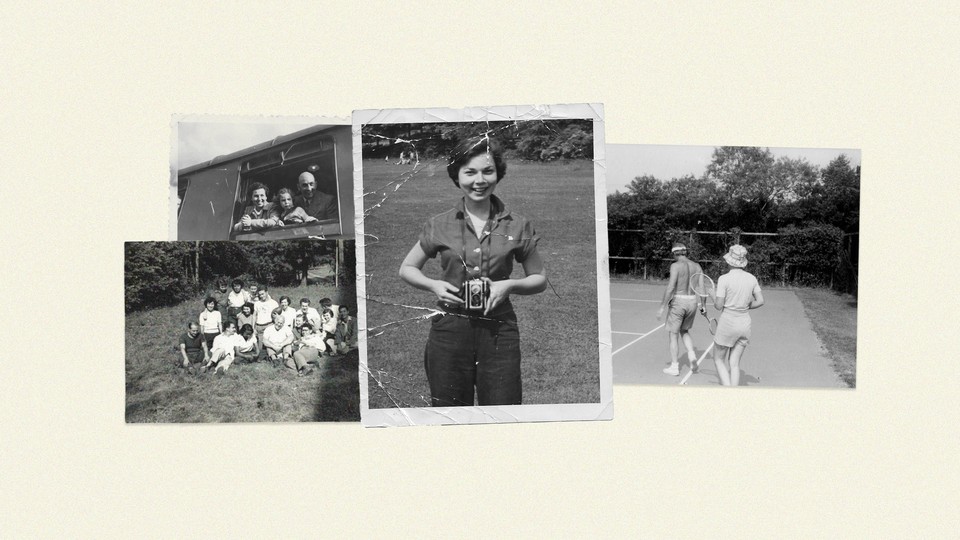

This is why her choice to turn to autobiography in her last book, Still Pictures, is so intriguing. From the moment you open it, the book does not present itself as a conventional memoir.

Instead, it is structured around a series of photographs, each igniting a short reminiscence—in other words, it may be the world’s most elegant annotated photo album. One can almost feel the reluctant autobiographer taking solace in the seemingly haphazard nature of the scrapbooking mode: the informal, offhand, almost accidental way of working. It feels as if she is almost tricking herself into it, as if writing a memoir is something that sort of happened to her while cleaning out a shelf or an attic, though of course each sentence, in true Malcolm form, turns out masterful. The sly self-deprecation of a box in her home labeled Old Not Good Photos characterizes the ambience of the entire project.

This associative, loose approach belies the self-seriousness and self-dramatization of most autobiography. Somehow, without a reader even quite realizing it, Malcolm’s memoir slips into being a commentary on memoir. Most autobiography assumes a proximity, an easy intimacy with the past, an unbroken flow. This one argues instead that memories must be fought for, interrogated, uncovered. As Malcolm puts it, “Memory glimmers and hints, but shows nothing sharply or clearly.”

Though she was famous for her journalism, Malcolm moonlighted as a collage artist, showing her collages in various Manhattan art galleries, and this book deploys the peculiar power of that art form. The collage artist puts fragments next to each other to make meaning, or spark energy, and this is what Malcolm does in Still Pictures.

We encounter Malcolm’s mother making profiteroles and roast squab for her daughters when they were sick; a photo of her father in drag at a Dadaist ball in the fashionable, intellectual Prague he inhabited before emigrating; the flower-patterned Italian plates that were stolen from a Midtown apartment rented for her adulterous affair with Gardner Botsford, the New Yorker editor she eventually married. For Malcolm obsessives, of whom there are many, these are intriguing glimpses of her life, but they are only glimpses. In the brevity and vignette-ish nature of each section, she evades delving too deeply into any one relationship or situation. She both reveals and does not reveal, exhibits and withholds, tells and hides. The quick riffs permit rapid turns and flights. The imperatives of the form allow her privacy, a stylish holding back, a reserve.

In the course of her reminiscences, Malcolm constantly calls our attention to what she does not remember, to the holes and lacunae and pockets of vagueness. She uses photographs, letters, snippets of diary entries, to try to pin down the past, to anchor her faulty and tentative sense of what happened. “I don’t know if my uncle was a domineering husband. I don’t know what the chronic exaggerated joking in the Edwards family meant about their deep relations.” “I don’t know where we slept or what we ate or did together.” She rigorously sorts through the evidence she has but comes up against doubts, patches of murkiness, limitations of perception. It begins to seem like her real subject is the haziness of memory, its little tricks and failures, its “perversity,” to use her word.

The mood of the journalist pushing for accuracy permeates the entire book: Who was I? Why did I act like that? What was going on in the room that I didn’t quite understand? We meet in its pages both young Janet the subject and Janet the rigorous reporter: “Was being given the petals from the ‘wrong’ flower so afflicting because it set me off from the other children, making me seem different?” “Did I become a journalist because of knowing how to imitate my mother?” “Didn’t I know something about why we had come and what we had escaped?”

Malcolm’s unusual form offers up the idea that all we really have of the past is a box of Old Not Good Photos that we must work very hard to understand. She is writing about the difficulty we have evoking our former selves, the many ways in which they are strangers to us. She asks, “Do we ever write about our parents without perpetrating a fraud? Doesn’t the lock on the bedroom door permanently protect them from our curiosity, keep us forever in the corridor of doubt?”

In some sense Malcolm’s book is the last argument in her career-long project to question the production of official stories, to reveal and illuminate the million vanities, exaggerations, character flaws that feed into their creation: the human error.

Sadly, Malcolm became too sick to write the last chapter she had planned, so the book ends with a photograph that her husband kept on his desk. It shows two people playing tennis from the back. They are not people he knew. He felt it was a perfect example of a terrible photograph. He kept it as a kind of memento of the absurdity of life. Malcolm included the photo in her first book, Diana & Nikon, as a joke, which she says no one noticed. She refers to this prank as “horsing around,” and in some sense she carries this high-level “horsing around” into Still Pictures as well. She is playing with the past rather than recording it uncritically. She is attuned throughout to the Dadaist sense of absurdity that she pinpoints in her parents’ Czech-emigre milieu, a dark humor. Ending with a photograph that means nothing to her, or means something because it means nothing, is the final subversion of her profound and mischievous scrapbook.

One is still left with a mystery, though. Why did Malcolm write an autobiography when the form vexed and repelled her? It may be that she entered a reflective mood at the end of her life, which made her want to conjure the past. It may be that she was tempted by the chance at artistic mastery in a new realm. She was not one to resist a challenge. She liked inventing or remaking forms. She thrived on the meticulous solving of aesthetic problems. About her struggle with autobiography she once wrote, “It may be too late to change my spots,” but she was clearly underestimating this particular leopard.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.