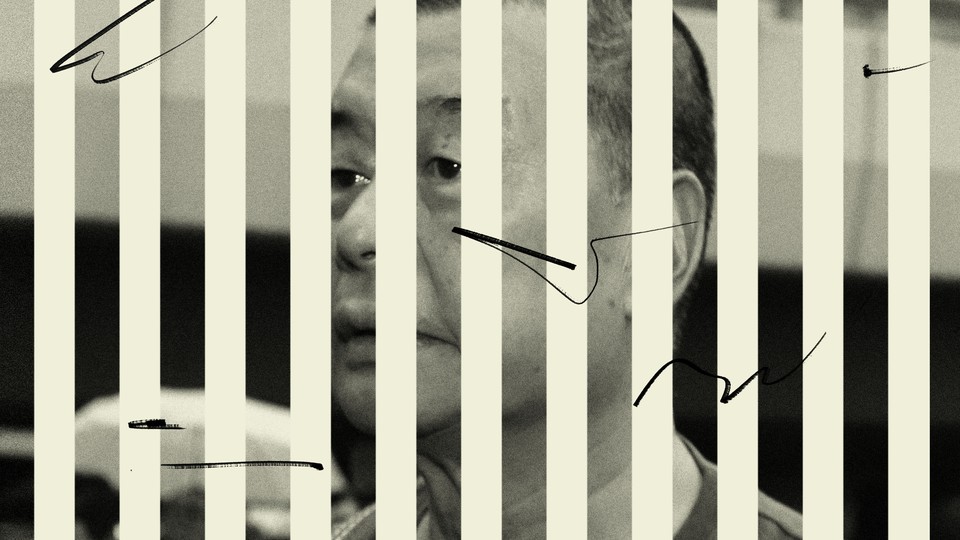

Why Beijing Wants Jimmy Lai Locked Up

Tightening its grip on Hong Kong, China is determined to make an example of the prodemocracy media tycoon.

HONG KONG—When Beijing imposed the national-security law on Hong Kong in 2020, its goal was not simply to stifle free expression and lock up dissenters. The idea was to subordinate every institution in the city, leaving the “one country, two systems” framework that granted autonomy to the Chinese territory an empty slogan. Henceforth Beijing would no longer tolerate criticism from Hong Kong, or protests on its streets.

With the prodemocracy movement of 2019–20 effectively crushed, the Hong Kong government and officials in Beijing have found additional uses for the law: to settle old scores and rewrite history. By prosecuting a relatively small number of high-profile cases under the national-security law, the authorities are portraying the movement not as a popular uprising but as a traitorous conspiracy of troublemakers in league with foreign powers. Any plot needs a ringleader, and the authorities believe they have one to fit their narrative: the media tycoon Jimmy Lai.

In this telling, Lai has been elevated to an omniscient actor—a puppeteer of the unwilling masses who for years used his wealth and publications (notably the Apple Daily newspaper), with assistance from the United Kingdom and United States, to dupe the city’s citizens into doing his nefarious bidding. Lai and his newspaper loom large in the most consequential national-security-law cases going to trial. Reams of prosecutorial documents portray him as a scheming “mastermind.” A source close to one trial involving Lai told me that Hong Kong’s national-security officers press suspects on their links to his business, cobbling the suspects’ answers together to fit a predetermined narrative.

“The police are making the story of Jimmy Lai,” this person, who asked not to be named for fear of police retaliation, told me. The decentralized nature of the 2019 movement is still viewed with paranoid disbelief by those who opposed it. The authorities “don’t believe that everything came from the ground up,” because they think “that is impossible.”

Already, in December, Lai was sentenced to more than five years in prison—a punishment, resulting from a case involving violations of a lease agreement, that one Hong Kong lawyer described to me as “shocking” in its severity. This harsh new sentence builds on lesser ones that Lai was already serving for participation in peaceful protests, yet Lai’s most daunting legal troubles are still ahead. He will go on trial again this year, this time explicitly for violating the national-security law; the accusation of being a chief instigator makes his the most serious of the dozens of people currently charged under the law. Lai’s case has been delayed as the Hong Kong government works furiously to forbid him from being represented by a British lawyer. In November, Hong Kong’s chief executive, John Lee, asked Beijing to intervene in the matter after the city’s courts ruled against the government’s repeated efforts to force Lai to change lawyers. Shortly before the end of the year, China’s top legislative body decreed that Hong Kong’s chief executive has the power to override the court’s decision.

A conviction for Lai would be a tidy conclusion to Beijing’s blatant exercise in rewriting history. Much as China’s leaders succeeded in recasting the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre, their narrative about the 2019 prodemocracy protests will strip agency from the hundreds of thousands of Hong Kongers who took part in them. The revisionist history will also absolve the authorities themselves, in both Beijing and Hong Kong, of their numerous failures of governance. Hong Kong’s courts, once lauded for their adherence to common law and judicial independence, will be pressed into serving this narrative.

Lai has a story of his own, a personal mythology he has recited countless times for reporters and rapt audiences. After his well-to-do family was stripped of its wealth when Mao Zedong came to power, Lai started his working life before he even reached his teens, carrying passengers’ baggage at a railway station in mainland China. One day, a man whom Lai had helped with his luggage took a chocolate bar out of his pocket and handed it to Lai. When Lai asked the man where he had gotten such a delicious treat, the man said “Hong Kong.” The city “must be heaven, because I’ve never tasted anything like that,” Lai recounted in The Hong Konger: Jimmy Lai’s Extraordinary Struggle for Freedom, a hagiographical documentary released in 2022. Making it to the city became his mission.

The young Lai arrived in Hong Kong a few years later as a 12-year-old stowaway on a fishing boat. He worked his way up from being a child laborer in a garment factory to becoming a salesman, jetting between Hong Kong and New York City, where he hustled clothing samples by day and partied until dawn at Manhattan nightclubs. On one trip, as Lai has often told, a lawyer he was dining with gave him a copy of Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom. Lai credited the book with changing his life, inspiring him to become an entrepreneur freed from the shackles of the state.

In 1981, he launched his own clothing brand. He called it Giordano—by his account, after a pizza parlor he wandered into one night in New York looking for a cure for the munchies after using marijuana. The Hong Kong–based company soon flourished by selling casual wear in fast-growing consumer markets across Asia.

Lai, however, was not content merely to become a multimillionaire. In 1989, as protests gathered momentum in China, he donated tens of thousands of dollars to the student demonstrators who gathered in Tiananmen Square, and he had T-shirts printed that bore images of the student leaders’ faces. After the Chinese authorities crushed the movement, Lai decided he needed a more formal platform for his message and ventured into journalism. He started Next magazine, a weekly publication, and then Apple Daily. The title was an allusion to the biblical tale of Adam and Eve and the tree of knowledge. “An apple a day keeps the liars away,” an early slogan proclaimed.

The entrepreneur’s outspoken criticism of the Chinese Communist Party made him an anomaly among the city’s business elites. “For Hong Kong’s big business leaders, especially those with interests in the colony that extend beyond 1997, allying with Beijing is simply good business,” a reporter at the International Herald Tribune noted in a 1991 article that highlighted Lai and his “unusual” position in the former British colony that was due to be handed back to China. But part of Giordano’s parent company was owned by a Chinese state-controlled enterprise, and Lai said he had no problems with interference from the mainland.

The congeniality did not last. After Lai wrote a mocking attack on Chinese Premier Li Peng in a 1994 issue of Next, Giordano’s stores on the mainland faced bureaucratic harassment that continued even after Lai resigned from the company’s board and sold the remainder of his stake to focus instead on his media empire. With his publishing ventures, he had, he said, entered the business of delivering “information, which is choice and choice is freedom.”

Lai’s version of freedom in his publications involved an eclectic, often sensationalist mix: Columns from leading prodemocracy advocates and political investigations ran alongside stories of sex scandals and celebrity gossip. Sometimes, Apple Daily breached journalistic boundaries and became the story itself. In 1998, the paper was obliged to print a front-page apology for its unethical and salacious coverage of a family murder-suicide. On another occasion, a staff reporter was arrested after he was discovered to have been paying police officers for information.

Despite these missteps and setbacks, Lai was undaunted. He refused to be cowed by threats—either from the authorities or from Hong Kong’s elite. He tangled with the city’s tycoons, whom he accused of pulling advertisements from the paper when he made an ill-fated foray into e-commerce. His home and office were firebombed on more than one occasion. Challenged by his own reporters, during a customary yearly interview, about rumors that he had slept with prostitutes before he married (for a second time) in 1991, Lai confirmed the stories, prompting coverage by the International Herald Tribune.

His vocal support of democracy and his defense of a free press gave Lai international media stature, and made him someone sought out for snappy quotes. The latitude his publications enjoyed became a bellwether for the freedoms that were meant to be preserved in Hong Kong under the agreement concluded in the run-up to the 1997 handover. “We are afraid, but we don’t want to be intimidated by fear or blinded by pessimism,” Apple Daily had declared in its first edition. For the next two decades, Apple Daily carved out an enviable position in Hong Kong’s bare-knuckle newspaper business, becoming one of the city’s most popular and trusted news sources.

Lai became a particular darling of the American right, which had long heralded Hong Kong as a pro-business utopia of low taxes and limited welfare where bootstrapping immigrants from the mainland could prosper—just as Lai had. William McGurn, a journalist and later a speechwriter for George W. Bush, became Lai’s godfather when Lai converted to Catholicism in 1997, shortly before the handover. John Bolton, who worked in numerous Republican administrations and served as a national security adviser to President Donald Trump, first met Lai in Hong Kong in the late 1990s. “I was incredibly impressed by Jimmy,” Bolton told me. He “really had a vision for what Hong Kong could be and what kind of society he wanted in Hong Kong.”

Lai also became friends with the libertarian economist Milton Friedman and accompanied him to China. A vocal proponent of free-market capitalism himself, Lai argued that the U.S. had for too long tried to work with China, rather than confront the country and its leadership. “You in the West need to have confidence in the superiority of your own system,” he said, when delivering a speech at the Hoover Institution in 2019. “China is never embarrassed to assert its own values even though these values are rooted in perhaps the most horrible Western export, Marxism. America needs to have the same confidence in its values and its own moral authority.”

This improbable run as an avatar of press freedom lasted until the morning of August 10, 2020, when more than 100 police officers raided the headquarters of Apple Daily. Lai was escorted through the newsroom in handcuffs after being arrested. Despite the raid, the newspaper continued to publish for nearly a year. But police returned in June 2021, and the newspaper’s bank accounts were frozen. The final edition of Apple Daily appeared on June 24.

Hong Kong’s prodemocracy political parties and activists, though often lumped together, span a spectrum of political leanings. And despite doling out money to different prodemocracy groups—donations revealed in 2014 when hundreds of his financial files were leaked—Lai was not universally beloved. Some felt that he was too close to the city’s old guard of moderates, whom younger generations believed had little to show after decades of pushing for incremental change, particularly after the Umbrella Movement limped to an end in 2014. Apple Daily was sometimes criticized for racist and sexist coverage, particularly from its more spirited columnists.

In 2019, when millions took to the streets and protesters sought international support, prominent activists and prodemocracy lawmakers turned to Washington. Lai capitalized on his Republican connections and had a series of meetings with Bolton, Vice President Mike Pence, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. Bolton told me that Trump cared little about Hong Kong, other than being briefly impressed by the size of protests—the city “had joined Taiwan on the list of minor irritants he didn’t want getting in the way of his relationship with Xi Jinping,” Bolton said. Still, these senior Trump officials regarded meeting Lai as important because it showed that “America as a whole was strongly supportive of what the Hong Kongers wanted to do.”

Back at home, though, press coverage of the meetings enraged the Hong Kong government. Chinese state-backed media denounced Lai as a traitor who had betrayed the nation in favor of American interests.

At the same time, Lai faced criticism from activists in the prodemocracy camp. Despite his support for the protests, he was attacked for not backing more radical actions against police misconduct. Tam Tak-chi, a prodemocracy activist with the People Power party, who pleaded guilty to a national-security offense after taking part in an unofficial primary vote in 2020, was one who saw Lai as too conservative. During a recent interview from jail, where he is serving a 40-month sentence for sedition, Tam told me Lai was “not as progressive” as his own party.

Nevertheless, Lai’s activities would soon land him in trouble with the Hong Kong authorities. In 2019, Lai started helping a pair of prodemocracy activists, one of whom was an awkward IT worker from Hong Kong named Andy Li. Li had thrown himself into the 2019 movement and became a key member of a group that aimed to raise awareness of the protests abroad by purchasing newspaper ads. After the success of the campaign and an influx of donations, the group, Stand With Hong Kong, expanded into lobbying and meeting with foreign-government officials. Li, according to people who know him, had a robotic work ethic, seemingly able to grind for days without sleep. A lawyer who represents him declined my request for comment.

In August 2020, Li was arrested for violating the national-security law on a charge of conspiring to collude with foreign forces. Less than two weeks after his arrest, while out on police bail, Li tried to flee to Taiwan by boat but was apprehended, along with 11 others. According to two people with knowledge of his case, Li flipped and agreed to cooperate with officials in building a case against Lai.

In August 2021, Li pleaded guilty, as did his co-defendant, Chan Tsz-wah, a paralegal. Police investigating the two had an almost obsessive focus on Lai and the U.S. government, according to one of the two people I talked with who were familiar with the investigation. Documents in the case underscore the point: The bulk of the 30-page summary of facts submitted to the court focuses primarily on Lai. The prosecutors paint him as the “mastermind” of a fundraising-and-lobbying effort that, in reality, was largely a crowdsourced undertaking by activists that began on a popular message board.

The court documents also almost exclusively blame Lai for pushing the U.S. government to pass legislation aimed at punishing Hong Kong for its loss of autonomy from the mainland, and later to sanction government officials both in the city and in Beijing. The Hong Kong authorities described Lai in court documents as representing “the highest level of the syndicate”—as though he were a triad boss.

Although Lai was involved in Stand With Hong Kong, to portray him as its architect grossly inflates his role, according to the person with close knowledge of one of Lai’s trials. “They have to have someone who admits to being the mastermind,” this person told me. “Jimmy stood out for them: He said a lot of things, he has money,” so, in the eyes of the government, “he has to take the responsibility for the whole movement.”

Lai’s influence on recent U.S. policy making is also exaggerated. Trump, for all his anti-China bluster, was unconcerned with human rights and primarily interested in signing a trade deal with China. A more forceful bipartisan response to the situation in Hong Kong came only after Beijing imposed the national-security law—but even then, Washington held back on the harsher measures advocated by some within the administration. A plan to help Hong Kongers resettle in the U.S. was scuttled by Republican Senator Ted Cruz in December 2020. A temporary order enacted by President Joe Biden to permit extended stays in the U.S. for Hong Kong residents is set to expire next month. Whatever influence Lai had over any of this is probably negligible.

Lai is also at the center of a court case against six former Apple Daily staff members, who pleaded guilty under the national-security law in November to charges of conspiracy to collude with foreign forces. In court documents, prosecutors construe routine editorial meetings and banal newsroom decisions as conspiratorial intent—including material published by the newspaper that prosecutors claim was masquerading as news but was really calling for protests or violence. Again, Lai is portrayed as the ringleader of a plot to elicit foreign interference that would “impose sanctions or blockade, or engage in other hostile activities against” China and Hong Kong. That prosecutors will call for Lai to receive the maximum penalty, a life sentence, seems a near certainty.

What drives the authorities’ fixation on Jimmy Lai, rather than any other prodemocracy figure, is a question that prompts a range of answers. Other candidates for ringleaders and such harsh punishment certainly exist. Joshua Wong, who rose to prominence as a teenage protest leader, has a larger global reach and greater name recognition than Lai. Martin Lee, the genial “godfather of Hong Kong democracy,” was a regular figure in Washington long before Lai, twice meeting with President Bill Clinton in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In Hong Kong itself, other activists who vaulted to prominence during the protests are far more popular than Lai.

Steve Tsang, the director of the China Institute at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies and the author of several books on Hong Kong, told me one theory of the obsession. Beijing understands, he said, “that logistics is key to eventual success in any competition,” and that cutting off Lai’s ability to provide support to prodemocracy groups was more pressing than silencing politicians shouting slogans. Another theory he offered was that the persecution was simply a scare tactic. “By treating Lai harshly,” Tsang told me, “the party will be able to send a clear and powerful signal to dissidents in Hong Kong that none of them can be safe, if all the money and overseas profile Lai has cannot protect him.”

When I recently interviewed C. Y. Leung, Hong Kong’s acerbic former chief executive, for another project, he angrily insisted on steering the conversation back to his own expansive and detailed version of the Lai conspiracy. Leung has become extremely jingoistic of late and spoke of Lai with the seething anger of a QAnon follower.

According to Leung, Lai has been covertly working with the British government ever since 1997 to split Hong Kong from China. To achieve this, Lai bankrolled the city’s prodemocracy camp to foment a pro-independence revolt. “He had all the leading opposition politicians in his pocket,” he told me, “and through them he mobilized people and he had his propaganda machinery.”

When I asked Leung to provide evidence of his claims, he told me that this would be like asking the CIA to unveil its secrets. “Of course I can’t,” he said. Pressed on why, during his five years as chief executive, he did not move to put an end to Lai’s schemes, Leung responded, “We have to have a legal basis, whatever we do.” In other words, none of Lai’s political activities were illegal before the national-security law passed.

But with that in place, Beijing has weaponized the courts against its longtime adversaries—just as Chinese state media continues to promote Lai as the poster boy of everything nefarious in Hong Kong. For both purposes, Lai has a sufficiently high profile and is convincingly rich enough to have fomented a subversive uprising; and, amid the nationalist atmosphere that prevails in Beijing, Lai also had highly suspect foreign connections that reached close to the center of power in Washington, particularly during the Trump administration.

By turning to its old playbook of assigning blame to a hostile force at home backed by support from abroad, the Chinese Communist Party is falling into a trap of its own creation. Given the sentences that Lai is likely to receive for his alleged crimes, Lai could very well be imprisoned for the rest of his life. In looking for a scapegoat, Beijing may find it has created a martyr.