The Writer’s Most Sacred Relationship

Creative partnerships can be a challenge for fragile egos—but they also provide a lifeline in difficult times.

Making a living as a writer has always been an elusive pursuit. The competition is fierce. The measures of success are subjective. Even many people at the top of the profession can’t wholeheartedly recommend it. The critic Elizabeth Hardwick, Darryl Pinckney recalls in his evocative new memoir, “told us that there were really only two reasons to write: desperation or revenge. She told us that if we couldn’t take rejection, if we couldn’t be told no, then we could not be writers.”

In spite of these red flags, countless people set out on this path. One lifeline, if you’re lucky enough to find it, is mentorship. Literary mentors offer the conventional benefits: perspective, direction, connections. But the partnerships that result are less transactional and more messy and serendipitous than those that tend to exist in other industries. While many people might think of such arrangements as altruistic or at least utilitarian, Pinckney’s book, which chronicles his tutelage under Hardwick, shows that artistic mentorships, especially literary ones, are far more fraught. Together, he and Hardwick weathered two intersecting careers, each with fallow periods and moments of success. This can be a challenge for creative, fragile egos—leading to a fair amount of projection, blame, and tension. And yet, the mentorships that endure allow for unpredictability and evolution.

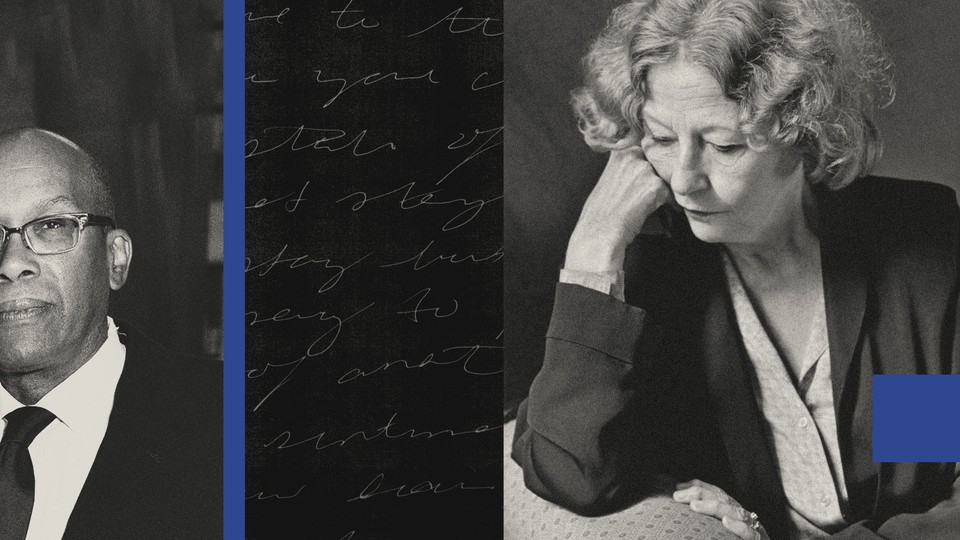

In his memoir, Come Back in September: A Literary Education on West Sixty-Seventh Street, Manhattan, the critic and novelist Pinckney writes about his coming of age in the 1970s and ’80s under the spell of two great lions of 20th-century American letters, Hardwick and Barbara Epstein. These “unrepeatable women” are best known as two of the co-founders of The New York Review of Books, but they had vibrant and influential careers beyond the magazine: Epstein as an editor and tastemaker (one of her earliest projects was editing The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank), and Hardwick as a critic, novelist, and professor.

Other literary figures of the time (Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, Susan Sontag, Philip Roth) occupied the spotlight then and for decades to follow, but of late, Hardwick has enjoyed a posthumous revival, celebrated for her diligent and relentless work in a few recent books (Cathy Curtis’s dry but noteworthy 2021 biography, A Splendid Intelligence; Saskia Hamilton’s brilliant The Dolphin Letters, which collects Hardwick’s correspondence with her ex-husband, Robert Lowell; and two posthumous essay collections, one of which was edited by Pinckney). Epstein surfaces throughout these books as a trusted friend of Hardwick, and a superb editor to both Hardwick and Pinckney.

As an undergraduate at Columbia, with aspirations of becoming a poet, Pinckney took a creative-writing class with Hardwick. But it wasn’t long before Hardwick realized that her student’s talents rested not in poetry but in prose. Soon enough, she was inviting him for weekly dinners at her home. These gatherings became a thoroughly informal seminar of their own—many featuring visits from Hardwick’s friends and fellow writers. As formal academic boundaries dissolved between Hardwick and Pinckney, it became clear that the classroom was only one place to grow as a writer.

Hardwick’s role as Pinckney’s mentor was different from that as a teacher; nurturing talent was something more sacred and essential than instruction. “That writing could not be taught was clear from the way she shrugged her shoulder and lifted her beautiful eyes after this or that student effort … But a passion for reading could be shared, week after week. The only way to learn to write was to read,” Pinckney remembers. As a mentor, Hardwick helped fill the gaps in Pinckney’s education by offering book recommendations and fostering discussion, but her influence was also felt in deeper and subtler ways. By welcoming Pinckney, as an equal, into her home and among her friends, she helped him realize that there was a place for him in the world of letters. For a young man hungry to burst past the limits of his experience, there could be no better circle in which to insinuate himself. Hardwick benefited as well: The relationship was a means of reinvention and renewal, in which her ideas, too, could flourish.

But this wasn’t utopia. Throughout the memoir, Pinckney and his peers grapple with familial expectations and judgments, as well as with the threat of AIDS. New York had been an escape for these precocious undergraduates who kept their sexuality a secret from their families back home; mentors like Hardwick provided the answers and advice that they couldn’t get from their biological families. Hardwick says to Pinckney at one point: “You came to New York to be what you are … A mad black queen.” But these elders didn’t always fully grasp what young writers needed most.

Pinckney notes the friction that surfaced between Hardwick, an older white woman from the South, and himself, a young, Black, gay man from the Midwest, recalling instances when her language was insensitive or even offensive. Beyond these tensions, there was also Hardwick’s frustration at her own stalled ambitions, which seemed to manifest itself through admonishments of Pinckney: “Why are you writing ten pieces for seven hundred and fifty dollars when you could have had an advance of seventy-five hundred dollars for twenty pages?” she asks of Pinckney, who was making his living reviewing books instead of writing them. And yet, how much of that tough love was projection? Hardwick seemed to be directing her critical gaze inward, asking herself what she had to show for a life’s work.

As their relationship progressed, Hardwick began to express insecurities—both in her role as a mentor, and in her career as a writer. “I think the worst thing that ever happened to you was meeting me,” she half-jokes to Pinckney, meanwhile encouraging him to “make your book salable” and not be “too literary all your life.” And when it came to writing another novel after her acclaimed Sleepless Nights, she confided her fears in him: “I’m so scared. What am I doing? Don’t be like me.” These episodes reveal the unique intimacy and fragility of the relationship. After the initial hierarchy of mentorship, clear authority fades as the partners trade off as teacher and student. The stronger of the two (years and experience being irrelevant in moments of self-doubt) can lead the other out of these rough patches. But too many instances of vulnerability can wear down a relationship.

Ultimately, about 390 pages into the memoir, Pinckney leaves New York City for Berlin on New Year’s Eve of 1987. The move doesn’t come out of nowhere. Throughout the book, Pinckney foreshadows the impact of AIDS on his community and the city at large, and describes how he and his circle lost countless friends in the 1980s. At this point, his window as a precocious young writer was closing as well, with no published book to show for it. It was time to push himself to a new level.

Rather than scrutinize his reasons for leaving New York, Pinckney simply marks his exit by abandoning his first-person narration for Hardwick’s and Epstein’s voices, presented in a selection of letters and interspersed with his own journal entries from around the same time. The letters are offered without context or analysis; they leave much unsaid of his departure, but reflect his mixed emotions about it.

Ultimately, this is not only a book about the drama of these deep, lifelong relationships. What Pinckney seems to want to elevate is their best elements: enthusiasm, forgiveness, support, continuity. Time trudges on, and from afar, Pinckney receives word of friends and colleagues who have passed away. With these losses, the memoir closes on a bittersweet note. Pinckney remembers Hardwick quoting the poet Marianne Moore: “After everything we have loved is lost, then we revive.” Literary mentorship offers the power of a phoenix. Even at a writer’s lowest point, the lifeline of conversation and intellectual exchange urges them forward.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.