What Kind of Man Was Anthony Bourdain?

He was so damaged, and yet he showed us so much of the world.

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

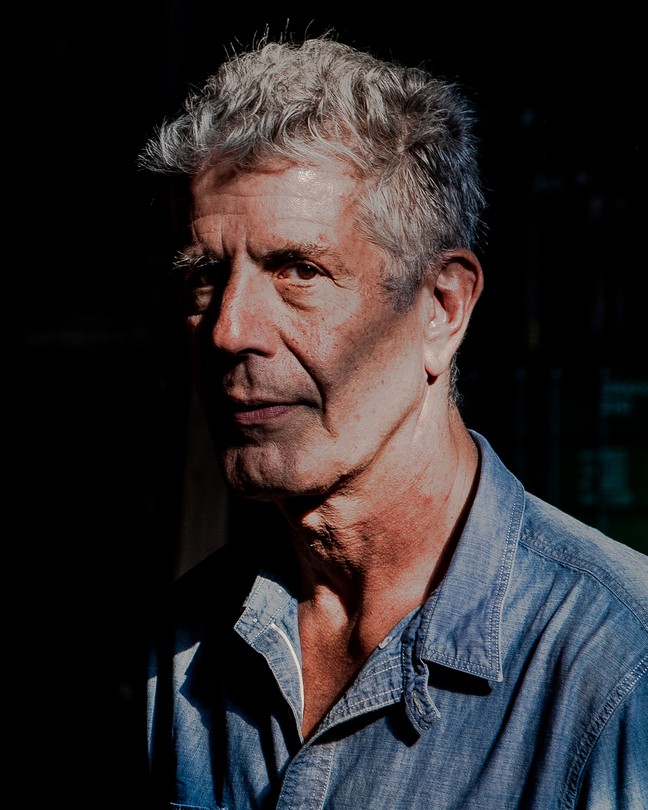

“Travel isn’t always pretty,” Anthony Bourdain once said, wrapping up an episode of one of his shows in his distinct staccato voice-over. “It isn’t always comfortable. Sometimes it hurts; it even breaks your heart. But that’s okay. The journey changes you.” Over his 15 or so years on television, Bourdain took Americans to places they were unlikely to go and introduced them to people they were unlikely to meet. At his best, he stripped away the filters that a superpower imposes on the world—good and evil, victor and victim—and found an essential humanity that we all share. In a time when social media elevates bombastic voices certain of their righteousness, Bourdain offered ambiguity that was somehow reassuring: It’s possible, his shows suggested, to look honestly at the world’s diversity, complexity, and occasional depravity, and be better for it.

Americans tend to reserve a place in the culture for a particular kind of man (and it’s almost always a man) who makes his own way: the self-destructive striver who succeeds outside the lines of any recognized rule book or established convention. All the better to have overcome adversity. Bourdain is at once a familiar and unlikely addition to that category. A former heroin and crack addict and celebrity chef who wasn’t particularly noteworthy as a cook, he vaulted into the popular imagination as a writer in 2000 with Kitchen Confidential, a gonzo-journalism trip through 20 or so years working in kitchens. He excelled as a celebrity, ready with a provocative quip and projecting a bemused demeanor that winked at the audience when he was the guest of some gossip journalist or overcaffeinated talk-show host: We all know these people are full of shit. And yet he went on to produce earnest and searching television shows, taking audiences everywhere from West Virginia to the Democratic Republic of Congo, finding a unique voice and a form of expression that managed to break through the incessant noise of our culture.

Americans also have a morbid fascination with famous people who die by suicide. Perhaps such a death speaks to a gnawing sense that there is a spiritual void at the epicenter of the capitalistic American dream: You can have it all and still be miserable. Since Bourdain died in a hotel room in Alsace, France, in 2018, there’s been something of a tug-of-war about how to remember him. Do we focus on the rich body of work that showed us the virtues of boundless curiosity and human resilience? Or do we obsess over the mystery of why the same person who showed us all those things ultimately said no to his own life? How do we reconcile the endless journey Anthony Bourdain took us on with the sad destination that it reached?

The tragic irony of Bourdain’s life and death is that the same interior darkness he succumbed to enabled the alchemy that he performed, again and again, on television: showing us three-dimensional human beings doing their best against often insurmountable odds. Recognizing this, I originally became fixated on Bourdain’s shows during the insomnia of my later years working in the Obama White House. My obsession only deepened after Donald Trump’s election, which led to the destruction of so many things that were important to me. Here was someone who wasn’t offering false optimism or mindless distraction. No matter where they were, the characters Bourdain introduced us to seemed to be searching imperfectly for the same simple things: community, authenticity, and integrity. It made me feel less alone.

In Down and Out in Paradise: The Life of Anthony Bourdain, Charles Leerhsen chooses to view Bourdain chiefly through the lens of his suicide. Throughout the book, different aspects of Bourdain’s life and personality are cast as foreshadowing his end: his rage against his middle-class New Jersey upbringing; a controlling mother and a father whose life ended in failure; an addictive personality and that self-destructive darkness; a yearning to be loved and a discomfort with those who loved him. The story works its way to a seemingly inevitable ending, punctuated by text messages exchanged by Bourdain and Asia Argento, the Italian actor who Leerhsen believes broke Bourdain’s obsessive heart. After seeing her in paparazzi photos with another man, Bourdain begged her to acknowledge his suffering and jealousy. “I can’t believe you have so little affection or respect for me that you would be without empathy for this,” he wrote. A day later, he was dead.

By ending on the texts, Leerhsen gives in to salaciousness, undermining what is otherwise a stylized and exhaustively researched celebrity biography. A former editor at Sports Illustrated, Leerhsen has the magazine writer’s ability to put us inside the life of a famous person: “Shadowy figures in tenement doorways? Perfect! This is how Tony, in 1981, wanted to lose his heroin virginity.” He also makes the interesting choice to focus on Bourdain’s early years, before we knew him. This is a gritty contrast to other recent Bourdain books and documentaries that lean heavily on the proud production-company and celebrity collaborators of his later years—which Leerhsen dismissively refers to as “Bourdain Inc.”

Whether you are a Bourdain fan or a relative newcomer to his story, you’ll come away with a better understanding of what made the man. Yet sometimes he comes across as a bit too intent on cutting Bourdain down to a more manageable life size. We learn, for instance, that he didn’t invite some of his high-school friends over to his house, and we get a full reproduction of one of his bad college poems. Of the latter, we are offered the judgment of a poet consulted by Leerhsen: “A poem trying too hard to be a poem.”

That may, in fact, be an apt, if unintentional, summary of Bourdain’s own stubborn determination to turn himself into an extraordinary man. He could, as Leerhsen reminds us, be insecure and act like a jerk. But he was also a serious enthusiast—for food, music, movies, and writing—who searched for decades for a way to measure up to the 20th-century American-male archetype he admired: a reckless and charismatic man like Hunter S. Thompson or Marlon Brando. Like his heroes, he strove to transcend the afflictions that Leerhsen details, and succeed on his own terms amid the sanitized and profit-hungry landscape of American culture. And after a middling career as a chef and one-off success as a memoirist, Bourdain, remarkably, found his outlet on an unlikely 21st-century medium: as a travel television host.

Leerhsen gets how Bourdain’s vices and neuroses helped him forge a bond with his audience. “It was comforting,” he writes, “for viewers to realize that the coolest-seeming guy in the world didn’t actually have life licked.” But Leerhsen is less successful at taking the next step: conveying how—or why—this sort of guy, damaged in many ways, someone who had never really traveled much before hosting a television series, ended up showing us so much. Bourdain brought the eyes and heart of an enthusiast everywhere he went, and he maintained a deep well of empathy for people who, like him, found it hard to reconcile what they loved about the world with what they didn’t.

Leerhsen tells us how Bourdain asked market-obsessed television executives to basically let him do whatever he wanted on camera. “That turned out to be a winning formula,” he writes, “and it left Tony with the distinct impression that, as he more than once said, ‘Not giving a shit is a really fantastic business model for television.’” That very much misses the point. Sure, in his earlier years on television, a big part of the allure was watching this tall, gangly American swear, eat a still-beating cobra heart, and drink to excess. But as his shows went on, Bourdain most definitely did give a shit. He had a knack for going to places that were along geopolitical fault lines. He exposed us to the emerging excesses of Chinese consumption years before Xi Jinping assumed power, took us to a Libya poised between the fall of Muammar Qaddafi and a descent into a second civil war, invited us to dinner with the Russian oppositionist Boris Nemtsov about a year before he was assassinated, and showed us countries in the global South struggling to find an identity despite the rampant inequality and unaccountable governments that remain a legacy of European colonialism and American adventurism.

In doing so, Bourdain often seemed to wrestle with what it meant to be American, which gave him so much opportunity while filling him with so much unease. In Laos, for instance, he eats with a man who has lost limbs to the unexploded ordnance left behind by America’s not-so-secret war. Bourdain is asked if he’s afraid to see the consequences of what his government did. “Afraid? No,” he responds. “Every American should see the results of war … I think it’s the least I can do, to see the world with open eyes.” At that moment, as in so many other Bourdain shows, this individual’s story is granted the same importance as the stories of people who usually appear on television—political figures, for instance, or celebrity chefs. This was his most subversive attribute, and he usually wasn’t preachy about it. On camera, he was just curious and willing to listen. And we could see—in real time—how the journey was changing him.

That’s what is interesting, and lasting, about Bourdain. What’s missing in this new biography is the possibility that the dark backstory Leehrsen tells contributed not just to Bourdain’s suicide but to his unusual empathy: Having known the rock bottom of heroin and crack addiction, the dislocation of not fitting in or feeling comfortable, perhaps Bourdain was better equipped to really see people struggling against forces that were too big for them to control.

In the end, that’s also what is most disturbing about his suicide. Leehrsen has an eye for the devastating detail. And to me, the most devastating of all is the fact that Bourdain had an “as-it-happens” Google alert for his own name, and that he spent the final hours of his life Googling Asia Argento hundreds of times, presumably staring at the same paparazzi photos over and over. How sad it is that Bourdain, who offered the promise of escape from the mundane social-media addictions of our time, spent his last days triggering himself while staring at screens. After a life of exploration, his last journey was down an online rabbit hole about his own failed romance.

Precisely because of the empathy he showed for his subjects, Anthony Bourdain the storyteller would have understood that his own life was bigger and more complex than how it ended. Like the archetypical American men he sought to emulate, he was able to find a voice that rebelled against convention and discovered something redemptive in the stories he told. For a time, he was able to outrun his own past and the weight of his celebrity. Until he couldn’t. As with travel, it’s up to us to decide what to take away from it all.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.