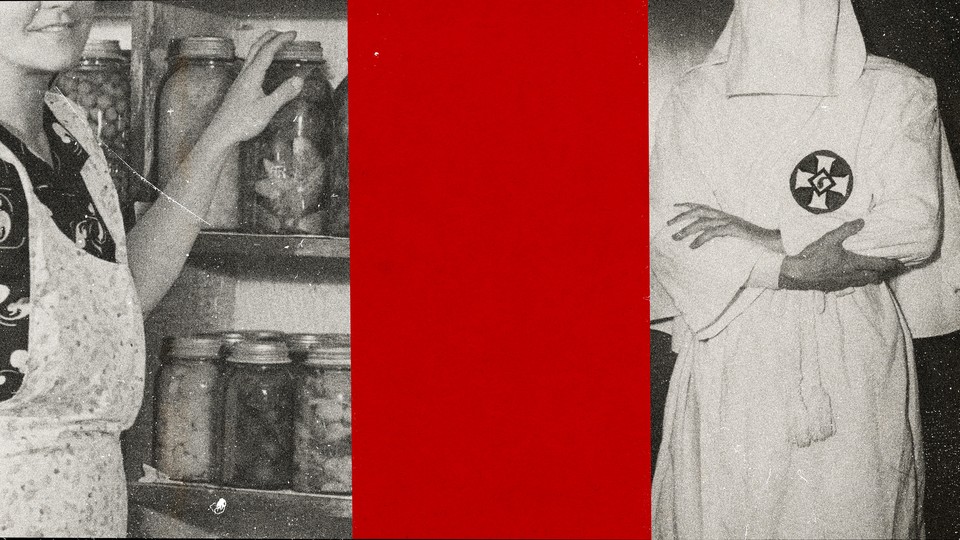

The Crunchy-to-Alt-Right Pipeline

Those living on the fringe of the left and the right share more in common than you might think.

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

On Twitter and TikTok over the past few weeks, scores of users have become alarmed about the uncomfortable coziness between the natural-food-and-body community and white-power and militant-right online spaces—the “crunchy-to-alt-right pipeline.”

Crunchy, coined as a pop-culture reference to granola, has come to refer to a wide variety of cultural practices, including avoiding additives and food dyes, declining or spacing out childhood vaccinations beyond what pediatricians recommend, and more extreme actions in pursuit of health, independence, and purity. Back-to-the-land living and alternative medicine are hallmarks of “crunch.” Much of this subculture is benign, a declaration of anti-modernism or slow living. But this largely white cultural space shares some preoccupations with right-wing organizations, which have used it for recruitment.

In the 1970s and ’80s, women in the emergent white-power movement, which gathered Ku Klux Klan members, neo-Nazis, skinheads, Christian Identity members, tax resisters, and other militant-right activists, deployed what we would now call “crunchy” issues as part of a wider articulation of cultural identity.

These bits of crunchiness included organic farming, a macrobiotic diet, neo-paganism, anti-fluoridation, and traditional midwifery. All of these are often thought of as leftist or “hippie” issues, but they appeared regularly in the robust outpouring of women’s publications in the white-power movement.

The surprise at the crunchy-to-alt-right pipeline, or at the closeness between the radical right and the radical left, reveals a problem with common ideas about left, right, and center in American politics. In general discourse, and too often in historiography, we use a measure that harkens back to World War II, with the left (aligned with the Communist U.S.S.R.) on one end, a flat line running through a political center (democracy and the United States), and the right on the other (where fascism and Nazi Germany reside). This idea of a political spectrum implies that left and right share little in common, and that they are diametrically opposed. It also positions fascism as far away from American politics, when recent history shows us quite the opposite.

The archive of the white-power movement—a vivid repository of letters, newspapers, personal correspondence, images, FBI files, news reports, and court records collected across decades—suggests that the reality is much more complex. Left and right not only grew close to each other in the ’70s and ’80s, but they sometimes shared much more with each other than with the political center.

Some political scientists have suggested a “horseshoe theory,” with the center as the rounded top of a horseshoe and the two fringes on either end, but inclined toward one another. This image, while evocative, isn’t quite right. In the archive, it looks more like a circle.

In the 1980s, for instance, white-supremacist compounds and hippie communes could exist in the same rural communities. Consider Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, the home of the white-separatist compound Aryan Nations. Coeur d’Alene also attracted other survivalists and people who wanted distance from the state, as well as environmentally inclined leftists attracted to the scenic lakes and mountains. Scholars have spent ample time on other alliances between neighbors in this period—such as the way the white-power movement radicalized its rural neighbors affected by the farm crisis of the 1970s.

Beginning in the ’70s, the alternative-lifestyle publication Mother Earth News ran articles on organic gardening and other issues championed by the left. Though the publication itself was not an organ of the white power movement, and indeed often espoused leftist positions, in at least one high-profile case, white power activists used its classifieds section to find one another. Robert Mathews, the leader of the white-power terrorist group the Order, met his first wife through the magazine’s personal advertisements. Mathews would lead the Order on a spree of racist and anti-Semitic assassinations, robberies, and infrastructure attacks that in many ways laid the foundation for the violent strategies used by white-power and militant-right activists today. (His wife, Debbie Mathews, had a movement career of her own that lasted long after her husband’s death at the hands of pursuing federal agents, and traded on his martyrdom.) The Mathews family lived in Metaline Falls, Washington, and commuted to nearby Hayden Lake, Idaho. In addition to the Aryan Nations compound, Hayden Lake and nearby Coeur d’Alene hosted tepee-dwelling hippie communities, alternative-lifestyle followers, northwestern outdoorsmen, fundamentalist Mormons, and survivalists unaffiliated or loosely affiliated with white supremacy.

Issues common to these groups accorded with ideas of purity, an interest in survivalism, and a deep distrust of the government. To be sure, the meaning of each of these issues would have been different to activists of different political persuasions, even in the same communities. Homeschooling, for instance, could be used in the white-power movement and as part of an intentional community or cult on the left. Midwifery might be powered by anti-feminism and strict gender divides on the right, or by women’s liberation and ideas of empowerment on the left. Anti-technology might be only selectively applied in a right-wing compound, such as the Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord, whose residents eschewed modern conveniences but manufactured land mines and automatic weapons in their remote Ozarks compound.

Another part of the Venn diagram is anti-fluoridation, the movement to oppose the government’s addition of fluoride to drinking water to reduce dental decay. This cause was taken up from an individual-rights perspective by libertarians, who argued that public-infrastructure needs should not outweigh people’s ability to make decisions about their own dental health. It was also treated by members of the right-wing John Birch Society as a communist conspiracy to undermine American public health. This alliance—between anti-communists and libertarians—is well documented in the history of American conservatism, and one can easily imagine how these two concerns could also be translated to social conservatives and survivalist evangelicals, to name a few other right-wing constituencies. Communism, after all, was seen as a threat to Christianity, and the individual-decisions argument resonated with social conservatives interested in other issues that depended on individual choice.

Anti-fluoridation was also taken up by a former executive director of the Sierra Club, among other environmentalists who argued that fluoride was a risk to ecosystems and a pollutant. Alexandra Minna Stern’s 2005 book, Eugenic Nation, documents the intersections between eugenics, hereditarianism, and other forms of white-supremacist pseudoscience on the one hand, and environmentalism in general and the Sierra Club in particular on the other. But such work has largely focused on the early 20th century, and it leaves out a main thread that connected the left and the right in the 1980s and ’90s: the idea of a looming apocalypse. White-power activists worried that fluoride would make people docile, such that revolution against the state and race war would be harder to accomplish.

In the white-power movement, anti-fluoridation and the fear that the state would contaminate the water (or allow communists to do so) is particularly significant, given that they were also interested in water contamination as a warfare strategy. In the early 1980s, one white-power group planned to poison Chicago, New York, and Washington, D.C.’s water supply with 30 gallons of cyanide in order to foment revolution. By making this nightmare about fouled water come true, these activists believed, they could awaken the public, revealing the state as the enemy and bringing people to the cause.

The cyanide plan, luckily for Chicago, was prevented when the poison was seized during the bust of a white-power compound. But like poison in the water, extremism has spread.

The crunchy-to-alt-right pipeline brings up another problem, one that is very real and dangerous: the attempts of the white-power movement and the militant right to find recruits. Yet another factor shaping what’s going on here is opportunism. White power is built around the movement’s ability to understand where our mainstream culture is vulnerable, and to use those vulnerabilities for its own purposes.

The second-era Klan, of the 1920s, was anti-Black and anti-Semitic, but it also used local tensions to galvanize recruits. Where Mexicans and Mexican Americans lived on and near the border, the Klan was anti-Mexican and had members in the Border Patrol. In the Northwest, where labor unions threatened profits in the timber industry, it was anti-union. In the Northeast, where immigrants were arriving in large numbers from Eastern and Southern Europe, it was anti-immigrant. And in Indiana, especially near Notre Dame University, it was anti-Catholic. In each instance, Klan leaders married their knowledge of local public opinion and the group’s broader objectives. They did so effectively, and the second-era Klan grew to some 4 million members, some of whom marched through the nation’s capital with their face uncovered.

This scapegoat-driven opportunism has long appeared alongside a sort of cultural opportunism. In the 1920s, as Kathleen Blee has shown, you could buy a women’s Klan auxiliary uniform in a fashionable cut that showed the right amount of ankle. In the 1980s, people in the white-power movement donned camouflage fatigues in part because they were a paramilitary formation interested in tactical readiness—but also because camouflage fatigues were cool in the ’80s, the age of paintball and Soldier of Fortune magazine and a panoply of Vietnam War movies.

In opportunistic movements, we have to ask real questions about earnestness. Are the activists using local scapegoats and camouflage fatigues in a shrewd and craven way to manipulate possible recruits? Or do they believe what they’re peddling? In the historical archive, there are examples of both kinds of behavior.

The pipeline is real; individual people are indeed being recruited into the militant right. Some of them make this journey through “crunchy” online spaces into white-power content, as the sociologist Cynthia Miller-Idriss has documented in Hate in the Homeland.

But the crunchy-to-alt-right-pipeline conversation gives us a chance to see something crucial that is often lost in depictions of right-wing formations. The white-power movement is not just men marching in the street. It’s also women sharing cultural materials through social networks. Women, and the cultural materials upon which they exert their most intense influence, are where we can see that this is a social movement.

So if you come across “crunchy” content that clicks through to “trad wives,” for instance—women who appear to simply be canning and making their own cleaning supplies, but who embrace “trad” (traditional aesthetics) as part of a broader white-power ideology and quickly move you along to more radical content—you’re encountering both a fluidity of belief and opportunism. Many people who advocate for “crunchy” issues expressed horror and surprise at the pipeline conversation because they felt manipulated—and yes, this is manipulation. It’s direct recruitment.

And let’s not be confused about the endgame. White-power activists, then and now, envision an all-white ethnostate or world achieved through profound violence, and no macrobiotic diet or apple-cider-vinegar remedy can ameliorate that message.