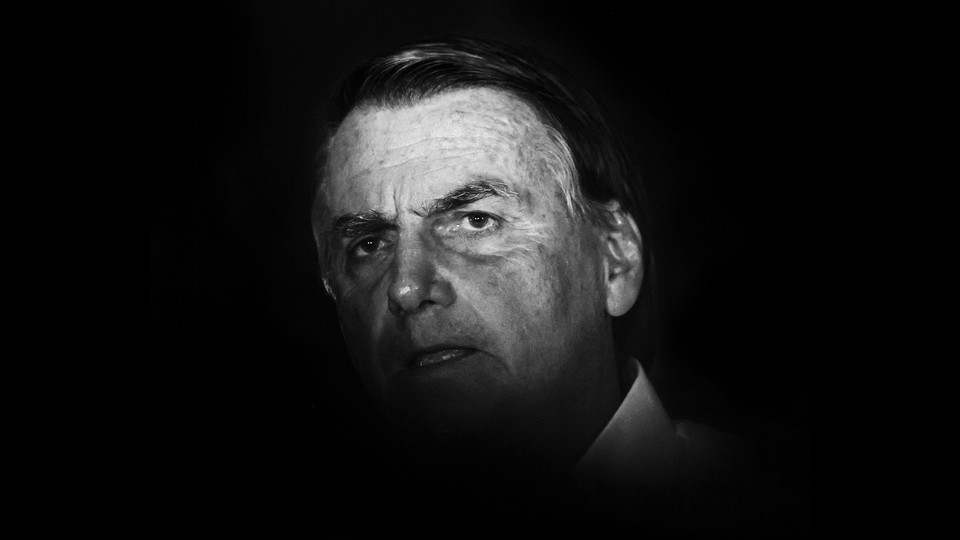

What Bolsonaro’s Loss Reveals About the Limits of Populism

The sight of a would-be authoritarian losing at the ballot box is welcome, but it’s too soon to declare a total victory over the demagogues.

As Sunday’s high-stakes runoff election for the presidency between Jair Bolsonaro, the far-right incumbent, and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, his left-wing challenger, approached, Brazilian political analysts kept returning to two big questions. The first was simply, “Who will win?” The second was more ominous: “Will the incumbent leave office if he loses?”

The answer to the first question came late on Sunday night. Lula clearly, if narrowly, defeated Bolsonaro, with 51 to 49 percent of the vote.

All of the attention then shifted to the second question. Throughout his time in office, Bolsonaro had given the army a more political role, praising the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985 and appointing generals to senior positions in his administration. In the past months, he’d lambasted the country’s voting system, claiming that it was rigged. Much seemed to indicate that he might follow the lead of Donald Trump and try to stay in power despite losing the election.

Lula gave a victory speech. Bolsonaro kept his silence. The Supreme Court called on him to acknowledge the outcome of the election. Bolsonaro kept his silence. Some of his own allies admitted defeat. Bolsonaro kept his silence. The suspense finally came to an end on Tuesday afternoon. Looking deflated, Bolsonaro appeared before the press at his official residence in Brasília, the country’s capital. Flanked by aides, he read a terse statement. “I’ve always been labeled antidemocratic, but unlike my accusers, I’ve always played by the rules,” he said. “As president and as a citizen, I’ll continue to follow our constitution.” Within two minutes, the usually attention-hungry president was out of sight.

Although Bolsonaro stopped short of conceding defeat or congratulating Lula, the implication was clear. Unlike Trump, he would not attempt to stay in power. His chief of staff soon confirmed that “President Bolsonaro has authorized me … to start the transition process.”

The handover period will still be fraught. Bolsonaro’s most hard-core supporters continue to protest against the election result. Some are even calling on the military to intervene. As Filipe Campante, a professor (and a colleague of mine) at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, told me, the country is going through a “low-key, slow-motion January 6.” But as Campante also emphasized, the much-invoked prospect of a coup has significantly dwindled.

Bolsonaro’s probable failure to hold on to office is an important moment in the protracted struggle between democrats and demagogues. As Brazil shows, even democracies that elect deeply antidemocratic leaders can prove resilient enough to stop them from seizing power. That should give hope to people struggling to preserve their democratic institutions against would-be strongmen all over the world. At the same time, Brazil is yet another indication that the threat from authoritarian populists is here to stay. Bolsonaro still won the support of nearly half the country—and may, like the man who now replaces him, one day mount a comeback.

As populist leaders rose to prominence over the past decade, it was unclear how long the trend would last. Some commentators assumed that their governments would soon collapse under the weight of their own contradictions. Others argued that populist governments had proved very durable previously, in part because many of them had succeeded in concentrating power in their own hands. But as these populists come up for reelection, the outcomes of these contests provide evidence that may resolve this dispute.

The first big reason for optimism came when Joe Biden’s defeat of Trump in 2020 demonstrated that removing an authoritarian populist from office was possible through the ballot box—even when he did everything in his power to stay put. That Lula has now repeated Biden’s feat in the world’s fourth-largest democracy bolsters the case.

Taken together, the defeats of Trump and Bolsonaro reveal why many populists find it hard to sustain their popularity and win reelection. When they first gain influence, in opposition, populists usually combine the absence of any substantial record in government with the promise of a radical break from the status quo. This allows them to attack the flaws and hypocrisies of the political system, both real and perceived. And so they can position themselves as truth-tellers who will “throw the bums out” and actually deliver for ordinary citizens—for example, by raising living standards.

Even their lack of support within mainstream institutions and political movements can be to populists’ benefit, because it seemingly testifies to their authenticity. Trump’s ascent is a good example. Polls consistently showed that most Americans objected to the outrageous comments he made about women and immigrants in 2015 and 2016. But because these slights were denounced by politicians who were themselves deeply unpopular, they demonstrated Trump’s willingness to break with the political establishment.

When populists win office, they begin to lose this outsider status, and their advantage fades. Before they come to power, populists have an incentive to overpromise. Once in government, they find it impossible to keep their word. Because they are inexperienced, many populists also weaken their position by making avoidable mistakes. They may struggle with basic competence, mismanaging the economy or failing to deal with such unexpected emergencies as a pandemic.

Populists claim to represent the true voice of the people, and usually move to short-circuit democratic controls once they are in office. But their campaigns are so polarizing that they cleave the country in two and mobilize their opponents. Especially in large countries whose power is geographically dispersed, like Brazil and the United States, the opposition usually retains key tools—such as strong representation in parliament or control over some cities and states—to slow the concentration of power.

All of these factors help explain Bolsonaro’s defeat. The rapid economic growth he promised never materialized. His handling of the pandemic was a deadly disaster. He never managed to win consistent control over Brazil’s Congress. By the end of his term, he was, in the eyes of many voters, defined by his failures—and had not yet amassed the power to defy their will.

Despite the electoral defeats of Trump and Bolsonaro, their opponents would be unwise to prematurely declare victory.

At the time of Biden’s inauguration, in January 2021, many observers judged that Trump had finally lost his hold over the country, and perhaps his party. Less than two years on, those predictions look naive. Biden’s victory was clear but hardly commanding. His approval ratings remain near record lows for a first-term president at this stage of his term. Meanwhile, Trump retains a passionate fan base, and has succeeded in purging most of his critics from the Republican Party. Although he has not yet declared his candidacy for 2024, a return to the White House is far from unimaginable.

Bolsonaro may prove similarly resilient. Little more than 2 million votes separated him and Lula. Brazil is more unequal and arguably even more polarized than the United States; these divisions make it easy for Bolsonaro to continue stoking discontent among his base. And although Lula’s comeback relied on a broad coalition, he rose to power as a proud leftist, earning the fierce and probably enduring enmity of nearly half the country.

Like Trump, Bolsonaro will probably retain the fervent support of a substantial portion of the electorate, putting him in a good position to exploit the next political opportunity. If Lula makes significant missteps, or even if Brazil suffers some misfortune that isn’t under the control of the new president, Bolsonaro may regain momentum by blaming the government for people’s frustrations. And the opportunities for Lula to slip up are many: A global recession is on the horizon, corruption runs deep in Brazil, and some of his more extreme allies will try to push him toward unpopular policies.

There are two competing narratives about what the outcome of the Brazilian election means. Some see Bolsonaro’s defeat as a sign that the populist wave is finally cresting. Others see his support among the 58 million Brazilians who voted for him as a sign that democracy remains as embattled as it has ever been. But the two interpretations are not as far apart as they might seem.

When authoritarian populists win power, they usually do a lot of damage to democratic institutions. But this doesn’t mean that they are guaranteed to prevail. As often as not, they ultimately lose their hold on power.

Conversely, when authoritarian populists lose power, the most acute threat to democracy usually subsides for a few years. But that doesn’t mean it has ended. Authoritarian populists can retain an ability to shape the political system from opposition—even staging seemingly improbable comebacks, as Benjamin Netanyahu just did in Israel.

All of this suggests that neither a triumphant resurgence of democracy nor a definitive defeat of populism is likely to occur in the next few decades. Rather, authoritarian populists such as Trump and Bolsonaro will remain a major part of the political landscape. The battle with populism is not a transitory phenomenon, soon to be resolved in favor of either democracy or fascism. It is the new normal for the troubled yet resilient democracies of the world.