The Most Pathetic Men in America

Why Lindsey Graham, Kevin McCarthy, and so many other cowards in Congress are still doing Trump’s bidding

When he wasn’t melting down over how “very badly” he was treated or acting like a seditious lunatic, Donald Trump could be downright serene in certain Washington settings—and never more so than when he would swan in for dinner at the Trump International Hotel, a few blocks down Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House and the only other place where he would ever agree to eat.

Unlike the Obamas, who would sneak out for date nights at trendy restaurants, Trump was hardly discreet when he went out to dinner. For Trump, a big, applauded entrance was as essential to the experience as the shrimp cocktail, fries, and 40-ounce steak. Each night, assorted MAGA tourists and administration bootlickers would descend on the atrium bar on the small chance they’d get to glimpse Trump himself in his abundant flesh—like catching Cinderella at the castle, or Hefner at the mansion.

The hotel gave every impression of being a tight and well-managed operation, in contrast to the proprietor’s side hustle down the street. Lots of Washington reporters would hang around the establishment, too. We could always pick up dirt that Trump and his groveling legions tracked in. The place was crawling with them, these hollowed-out men and women who knew better. You might catch Rudy rushing out to smoke a cigar, red wine staining his unbuttoned tuxedo shirt (that was the night of the Mnuchin wedding, I think). Or see Trump’s favorite pillowy-haired congressmen—fresh off their Fox “hits”—greeting the various Spicers, Kellyannes, and other C-listers who were bumped temporarily up to B-list status by their White House entrée.

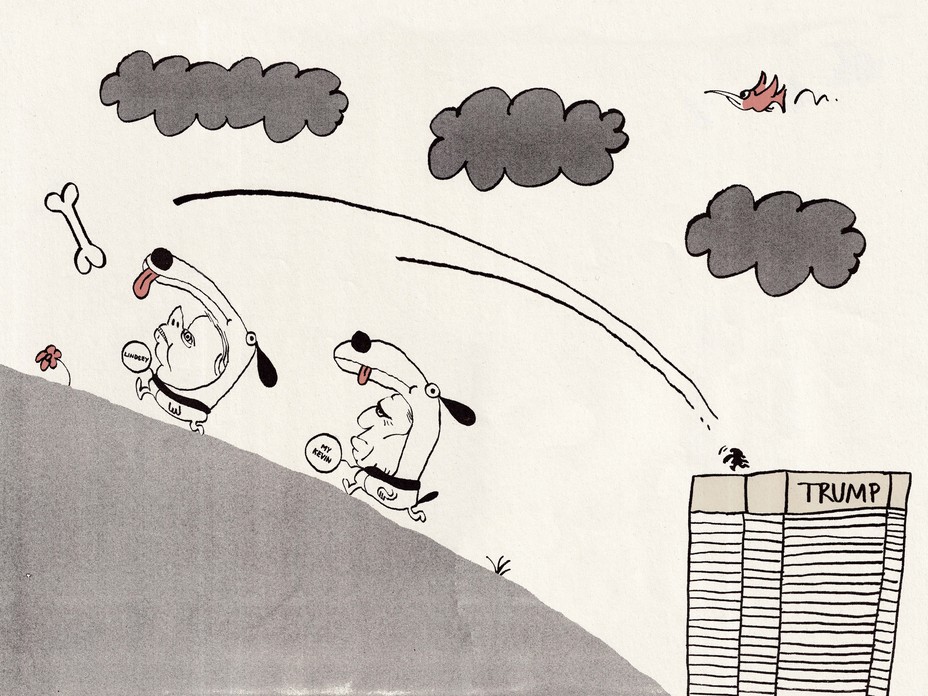

But the guests who stood out for me most were Republican House Leader Kevin McCarthy and the busybody senator from South Carolina, Lindsey Graham. I would sometimes see them around the lobby or steakhouse or function rooms, skipping from table to table and getting thanked for all the wonderful things they were doing to help our president. They had long been among the most supplicant super-careerists ever to play in a city known for the breed, and proved themselves to be essential lapdogs in Trump’s kennel.

McCarthy is a good bet to become the next speaker of the House in the likely event that Republicans win a majority in November. Graham remains perhaps Trump’s closest collaborator in the Senate, a frequent golf partner and nuanced handler of the presidential ego. This week, he was subpoenaed as part of an investigation into election meddling. He might now have to testify about what exactly he was trying to do when he called Georgia’s secretary of state wondering whether he really needed to count all those mail-in votes. “You know what I liked about Trump?” Graham asked last month during a speech at a Faith and Freedom Coalition conference in Nashville. “Everyone was afraid of him. Including me.” Laughter!

I will admit I never loved the Trump story. This sometimes surprises people. I have been covering Washington for many years; I’ve been accused of being a “keen observer” of the capital. Surely, I must have been thrilled to have such a ridiculous piece of work at the center of it all, right?

Well, no. I never found Donald Trump to be remotely captivating as a stand-alone figure. He’d been around forever and his political act was largely derivative. His promise to “drain the swamp” was treated as some genius coinage, though in fact the platitude had been worn out for decades by both parties. Nancy Pelosi promised to “drain the swamp” in 2006, just as the Reagan-Bush campaign had vowed to “Make America Great Again” in 1980.

Trump said and did obviously awful and dangerous things—racist and cruel and achingly dumb and downright evil things. But on top of that, he is a uniquely tiresome individual, easily the sorest loser, the most prodigious liar, and the most interminable victim ever to occupy the White House. He is, quite possibly, the biggest crybaby ever to toddle across history’s stage, from his inaugural-crowd hemorrhage on day one right down to his bitter, ketchup-flinging end. Seriously, what public figure in the history of the world comes close? I’m genuinely asking.

Bottom line, Trump is an extremely tedious dude to have had in our face for seven years and running. My former New York Times colleague David Brooks wrote it best: “We’ve got this perverse situation in which the vast analytic powers of the entire world are being spent trying to understand a guy whose thoughts are often just six fireflies beeping randomly in a jar.”

Better objects of our scrutiny—and far more compelling to me—are the slavishly devoted Republicans whom Trump drew to his side. It’s been said before, but can never be emphasized enough: Without the complicity of the Republican Party, Donald Trump would be just a glorified geriatric Fox-watching golfer. I’ve interviewed scores of these collaborators, trying to understand why they did what they did and how they could live with it. These were the McCarthys and the Grahams and all the other busy parasitic suck-ups who made the Trump era work for them, who humored and indulged him all the way down to the last, exhausted strains of American democracy.

The GOP’s shame, ongoing, is underscored by the handful of brave Republicans willing to speak the truth about Trump in public, before the January 6 committee and on the panel itself. The question now is whether they have any hope of wresting some admirable remnant of their party back from Trump’s abyss before he wins the Republican nomination for president in 2024 or, yes, winds up back in the White House.

Nearly a decade ago I wrote a book about Washington at its (seemingly) grossest and most decadent. This Town, the book was called, and it portrayed the pre-Trump capital as a feudal village of operatives, former officeholders, minor celebrity journalists, and bipartisan coat holders. Democrats and Republicans kept coming to Washington, vowing change, only to get co-opted, get richer, and never leave.

In retrospect, This Town reads like a comedy of manners. The revolving door between Congress and K Street, top Treasury officials selling out to Goldman—oh, the horror! Or, alternatively, who cares? We have such bigger issues today than feckless opportunists pregaming the Correspondents’ Dinner at Cafe Milano. People now toss around phrases like fundamental threat to democracy and civil war, and they don’t necessarily sound overheated. Deference to power in service to ambition has always been a Washington hallmark, but Trump has made the price of that submission so much higher.

Consider again the doormat duo—McCarthy and Graham. I’ve known both men for years, at least in the weird sense that political reporters and pols “know” each other. They are a classically Washington type: fun to be around, starstruck, and desperate to keep their jobs or get better ones—to maximize their place in the all-important mix. On various occasions I have asked them, in so many words, how they could sidle up to Trump like they have. The answer, basically, is that they did it because it was the savviest course; because it was best for them. If Trump had one well-developed intuition, it was his ability to sniff out weakness in people—and, I suppose, in major political parties. Nearly all elected Republicans in Washington needed Trump’s blessing, and voters, to remain there. People like McCarthy and Graham benefited a great deal from making it work with Trump, or “managing the relationship,” as they say.

McCarthy knew that alienating Trump would blow up any chance he had of becoming speaker, which had become the singular objective of his “public service,” such as it was. He cultivated Trump from the start. The president came to refer to McCarthy as “my Kevin,” a term of ownership as much as affection. But “managing the relationship” was often a daily struggle, McCarthy conceded, when I interviewed him for The New York Times in his Bakersfield, California, district in April 2021. “He goes up and down with his anger,” McCarthy said of Trump. “He’s mad at everybody one day. He’s mad at me one day … This is the tightest tightrope anyone has to walk.”

Once, early in 2019, I asked Graham a version of the question that so many of his judgy old Washington friends had been asking him. How could he swing from being one of Trump’s most merciless critics in 2016 to such a sycophant thereafter? I didn’t use those exact words, but Graham got the idea. “Well, okay, from my point of view, if you know anything about me, it’d be odd not to do this,” he told me. “‘This,’” Graham specified, “is to try to be relevant.” Relevance: It casts one hell of a spell.

“I could get Trump on the phone faster than any staff person who worked for him could get him on the phone,” McCarthy bragged to me. There was always a breathless, racing quality to both men’s voices when they talked about the thrill ride of being one of Trump’s “guys.”

What would you do to stay relevant? That’s always been a definitional question for D.C.’s prime movers, especially the super-thirsty likes of McCarthy and Graham. If they’d never stooped this low before, maybe it’s just because no one ever asked them to.

How do you sleep at night? Trump’s protectors were always being tormented by this nuisance question. What will future historians think about how you’ve conducted yourself? was another. Do you ever think about your … you know … legacy?

Early on, when wary Republicans were still publicly dreading where the Trump experiment might lead, you’d hear flashes of concern over how it—or they—might be adjudicated by those ever-hovering future historians. As his own presidential campaign was ending in 2016, Marco Rubio predicted that there would one day be a “reckoning” inside the GOP. “You mark my words, there will be prominent people in American politics who will spend years explaining to people how they fell into this,” Rubio told The New York Times. (Update: Rubio cleaned up his act, became a stalwart Trump patron, and we’re still waiting on that reckoning.)

“My attitude about my legacy is: Fuck it,” Rudy Giuliani told New York magazine’s Olivia Nuzzi in 2019 (his fly was unzipped at the time and he was drunk on Bloody Marys, per Nuzzi). Other versions were a bit more erudite. “Everyone dies,” Attorney General William Barr rhapsodized to CBS’s Jan Crawford in 2019. “I don’t believe in the Homeric idea that immortality comes by, you know, having odes sung about you over the centuries.”

I met with McCarthy in the spring of 2021 in a Bakersfield dessert joint—Dewar’s—where he and his high-school buddies used to go for milkshakes after football practice. He was scrolling through his phone to find photos of himself with old teammates. Being a big shot back in the day clearly remained a core part of McCarthy’s identity. Between licks of his chocolate ice-cream cone, he also kept showing me pictures of himself with celebrities. I tossed the pesky “legacy” question his way.

McCarthy kept his head down and pulled up a photo of the pope. Then one of President George H. W. Bush’s casket, his mother, his teenage self, with majestically feathered hair. “Here’s another of me with Trump on Air Force One,” McCarthy said. Then: “What did you ask me again?”

I repeated the question, suggesting that there might be far-reaching ramifications for his continued propping-up of Trump. McCarthy eventually looked up. “Oh, the Jeff Flake thing?” he said. No one’s putting up any statues to Flake at the Capitol, he pointed out, and muttered something similar about Mark Sanford, the former House Republican and governor of South Carolina.

I’d heard McCarthy give versions of this Flake-Sanford answer before. The response is worth unpacking, if only to underscore how dismissive McCarthy was of any suggestion that his conduct could bear historic weight beyond the day-to-day expediencies of keeping Trump’s favor. Flake and Sanford were both principled conservatives whose convictions were tested and affirmed over long careers. They freely condemned Trump throughout his rise, which led to inevitable abuse from the White House, pariah status within their party, and cancellation by “the base.” Sanford lost to a Trump-backed primary opponent in 2018, and it’s likely that Flake would have, too, had he run for reelection. Republican colleagues would often praise Flake and Sanford for their courage and principles—but only privately.

McCarthy wasn’t taking that risk. The son of a firefighter, McCarthy was a popular kid but a middling student. He attended community college, won $5,000 in a lottery, and opened a deli. That experience, he said, exposed him to the hassles that government regulation can impose on business owners. It made for a tidy Republican origin story, and before long, McCarthy had sold the deli and won a seat in the California state legislature.

Two decades on and many rungs up the org chart, McCarthy can be sensitive to perceptions that he is a lightweight whose career trajectory is owed purely to his Olympian brownnosing and backslapping capabilities. “I like that reputation,” McCarthy claimed to me, not persuasively, “because it helps people underestimate me.” McCarthy had come close to becoming speaker before, in 2015, but a Benghazi-related gaffe knocked him out of the running. Now the ultimate job is again within reach. Blinders on. Legacies are for losers. McCarthy learned from the master.

“My legacy doesn’t matter,” Trump told his longtime aide Hope Hicks a few days after the 2020 election, according to an account in Peril, by Bob Woodward and Robert Costa. “If I lose, that will be my legacy.” This became the essential ethos of Republican nihilism. By lashing themselves so tightly to Trump, Republicans could act as if the president’s impunity and shamelessness extended to them. His strut of cavalier disregard became their own.

No one did sunken-eyed contempt like Lindsey Graham. No one worked harder at caring less.

“Don’t care,” I overheard Graham say in early 2020 to a reporter on the Capitol subway platform who asked him whether his reputation had suffered because of his association with Trump.

“I don’t care if they have to stay in these facilities for 400 days,” Graham said on Fox News, about the hundreds of migrant children who had been separated from their parents and locked in cages. “I don’t care if we have to build tents from Texas to Oklahoma.”

Trump was a familiar type to Graham. His parents ran a dive bar, called the Sanitary Cafe, in the rural South Carolina town of Central. Short and pudgy, Lindsey was a tagalong figure who played the child mascot to the small-town characters who passed through the saloon. They nicknamed him “Stinkball.” He always gravitated to custodial, larger-than-life figures, or “alpha dogs,” as he called them.

For decades, John McCain served that role; he and Graham were best Senate friends, smoke-jumping into global hot spots and tense Capitol Hill negotiations. They knew where all the Kit Kats and Coke Zeros were stashed in the Sunday-show greenrooms.

No Republican spoke with more contempt for Trump during the 2016 primaries than Graham did. He called him a “complete idiot,” and “unfit for office,” among other things. But then Trump became president and deemed Graham fit to play golf with him. Suddenly Graham was getting called a “presidential confidant.” Colleagues would ask if he could deliver a message to the president, maybe score someone a birthday call or grease the skids for an endorsement tweet. “I try to be helpful,” Graham would say. The arrangement also proved “helpful” to Graham’s goal of continuing to represent deep-red South Carolina in the U.S. Senate. It got him into the clubhouse. It kept him fed and employed and on TV.

But Graham’s dash from McCain to McCain’s archnemesis made him a kind of alpha lapdog. Old friends kept asking, “What happened to Lindsey?” When I asked him this myself, Graham shrugged and said that he hated it when Trump attacked McCain, but that he himself had come to enjoy the president’s company. Any ambivalence Graham had over Trump’s conduct—for example, trashing his best friend to the grave and beyond—was buried by the fairy dust of relevance.

Graham was always saying how important it was to “get the joke” about Trump. “Getting the joke” is a timeworn Washington expression, referring to a person’s ability to grasp a shared truth about something best left unspoken. In the case of Trump, the “joke” was that he was, at best, not a serious person or a good president and, at worst, a dangerous and potentially criminal jackass.

“Oh, everybody gets the joke,” Mitt Romney assured me in early 2022 when I asked him if Senate Republicans really believed what they said in public about how wonderful Trump was. “They still are very aware of his, uh, what’s a good word, idiosyncrasies.”

Yes, politicians will sometimes say different things in front of different audiences. No big shocker there. But the gap between the public adoration expressed by Trump’s Republican lickspittles and the mocking contempt they voiced for him in private could be gaping. This was never more apparent, or maddening, as in the weeks after the 2020 election. “For all but just a handful of members, if you put them on truth serum, they knew that the election was fully legitimate and that Donald Trump was a joke,” Representative Adam Kinzinger, Republican of Illinois, told me last year. “The vast majority of people get the joke. I think Kevin McCarthy gets the joke. Lindsey gets the joke. The problem is that the joke isn’t even funny anymore.” The truth serum is not exactly flowing, either.

The last conversation I had with John McCain occurred in late 2017 as he battled the glioblastoma brain cancer that would kill him a few months later. He was about to leave Washington for the final time, and I ran into him in a Senate hallway. McCain was never shy about voicing his low opinion of Trump, but what was really eating at him then was how readily so many of his Republican colleagues continued to abase themselves before the president. “It comes down to self-respect,” McCain kept saying. He also noted that a big reason Trump remained so popular with GOP voters was because most of their putative “leaders” were too afraid to defy him. “Republicans who could shape opinion just keep sucking up to the guy,” he told me.

McCain was especially disgusted by his own sidekick’s capitulation. Yes, McCain understood Graham’s impulse to have a relationship with the president. He understood the need to emphasize base-friendly positions when you are “in cycle,” or have an election upcoming, as Graham did in 2020. What McCain objected to was the extravagance of Graham’s devotion to Trump. “Do you really have to keep saying how great of a fucking golfer he is?” McCain would ask Graham, according to people who were around them both during McCain’s final months.

Graham could indeed lay it on thick as he trailed a few caddie-like paces behind Trump on the fairway. He would tell the president he was doing “historic” things and reversing so much of the damage of the Obama years, and that his golf courses were just spectacular, sir. “I am, like, the happiest dude in America right now,” Graham gushed on Fox & Friends. “We have got a president and a national security team that I’ve been dreaming of for eight years.”

“Lindsey was really good at this game,” one senior Trump White House official marveled to me. Graham played Trump like a nine iron. He could also be stunningly open about how easy it was. There was an art to influencing Trump, Graham explained to me. “If you flatter him all the time, he’ll lose respect for you.” If Graham wanted Trump to do something, especially on foreign policy, he would just tell him that Obama would do the opposite. That “can be very effective,” Graham told me. “Obama drives him nuts.”

Graham’s defenses of Trump were often backhanded—in the vein of arguing that Trump was too incompetent to pull off whatever he was being accused of. “They didn’t know what they were doing,” he said when I asked him about Russia’s possible involvement with the Trump campaign. “The truth is, I don’t think that campaign could have colluded with anybody.”

Nonetheless, Graham reserved a tone of awe for his overlord. He could not believe what Trump could get away with. It created a mystique, especially among politicians, who tend to be rule-bound by nature and chronically petrified of being exposed as frauds. Trump had no such fear of rules or capacity for embarrassment. He was a pure and feral rascal.

As Jeff Flake prepared to leave the Senate in 2018, I asked him whether his fellow Republican senators ever tried to defend Trump to him. “No,” he said, chuckling. “Not his behavior, not his character, or his policies.” If there was any effort at all, Flake said, maybe his colleagues would insist that they were supporting Trump in the spirit of GOP loyalty. “The idea is to just embrace the president and hope he embraces you back,” Flake said. “And then try to sleep at night.”

I ran into Lindsey Graham the day before the 2020 election, in Rock Hill, South Carolina, at one of the last events of his Senate campaign. He stood in a parking lot surrounded by about a hundred supporters snacking from a buffet of Chick-fil-A. I asked how he was holding up. “I’m pretty much brain-dead,” Graham replied. He added that he liked his chances against his Democratic opponent, Jaime Harrison, whom he wound up defeating easily. “I’m just glad this thing will be over tomorrow,” Graham told me. Famous last words.

No one expected Trump to depart the presidency with any particular grace or statesmanship or other loser things like that. In the weeks after the election, his caseworkers had preached patience. “Give it time,” Graham kept telling people. He knew Trump had lost. He was just giving Trump the “space” he needed to come to grips with it. Likewise, Kevin McCarthy explained to squeamish colleagues that by echoing the president’s stolen-election claims on TV, he was merely trying to “manage” Trump until the defeated president could accept reality (always a shaky proposition).

“What is the downside for humoring him for this little bit of time?” a senior Republican official had told The Washington Post. The blind quote, oft repeated, became an instant classic in the genre of “takes that did not age well.” It was held up as a dark marker for a party that stood by to the point where a mob of the president’s supporters was spearing and pummeling a Capitol Police officer with an American flagpole (Old Glory still attached). “Humoring him” had essentially become the GOP platform.

But really, January 6 had to be the end of the line for Trump, right? Surely, this would be the moment when the fever broke. “Trump and I, we had a hell of a journey,” Graham said in a floor speech late that night. “But today all I can say is count me out. Enough is enough. I tried to be helpful.” His colleagues applauded, and the clip was played over and over, to illustrate the “good riddance” vibe of the moment. McCarthy told people he was going to ask Trump to resign. (It’s unclear whether he actually did; Trump claimed otherwise, and this is a rare case where I tend to believe him.)

But the breakup didn’t last. Graham later clarified that he meant only that he was “through” arguing about this particular postelection dispute, not through palling around with his favorite insurrectionist. Graham reiterated that he still enjoyed Trump’s company. He would continue to try to be helpful.

Trump departed Washington via Air Force One on January 20, with a final in-flight breakfast of grilled sirloin and cheesy grits with two over-easy eggs oozing on a buttermilk biscuit. He fired off a final last-minute pardon (on behalf of a Fox News host’s ex-husband), perhaps for relaxation, in lieu of Bible reading or something.

Exactly eight days later, McCarthy followed him to Mar-a-Lago. Trump felt that McCarthy had not been “nice” to him on January 6, when the minority leader called the president to nudge him about those annoying supporters of his who kept pillaging through the Capitol with nooses and clubs. Not civil! “The relationship,” McCarthy determined, required some tending to.

So, there they were, Donald and his Kevin, side by side again, reunited and it felt so good. In the photo that shot across social media, the old besties held the same clenched smiles and seemed to both be sucking in their tummies like bros of a certain age do.

McCarthy’s visit set off a parade of ring-kissing pilgrimages. Graham headed down to Florida again and again, so often that his host couldn’t help but marvel. “Jesus, Lindsey must really like to play golf,” Trump told an aide, according to a report in The New York Times. Graham “would show up at Mar-a-Lago or Bedminster to play free rounds of golf, stuff his face with free food, and hang out with Trump and his celebrity pals,” observed Stephanie Grisham, the former White House press secretary and top aide to Melania Trump, in her memoir. Grisham wrote that she and some colleagues referred to Graham as “Senator Freeloader.”

In April 2021, Senator Rick Scott of Florida showed up in Palm Beach to present Trump with the first-ever “Champion for Freedom” trophy, an award Scott invented just for that momentous occasion. It was kind of a lame trophy, to be honest—a puny silver bowl, roughly the size of the participation trophy my daughter got for her incredible hard work and dedication on the fifth-grade soccer team (so proud of you, Franny!). But Trump, who held the memento out for the cameras like a hot-fudge sundae, beamed at the recognition. Did Obama ever win a Champion for Freedom trophy? Don’t think so!

Watching the procession of GOP genuflectors, I was reminded of Susan Glasser’s 2019 profile of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in The New Yorker, in which she quoted a former American ambassador describing Pompeo as “a heat-seeking missile for Trump’s ass.” This image stuck with me (unfortunately) and also remained a pertinent descriptor for much of the Republican Party long after said ass had been re-homed to Florida.

“McCarthy started all of that,” Liz Cheney told me last summer. She’d had no advance warning of McCarthy’s visit to Palm Beach, and was stunned when she saw the photos. She confronted McCarthy: Why? She told me he explained that “the Republican Party was changing, and they all had to adapt. It was no longer the party of Dick Cheney.” This did not go over well.

“When we look back, Kevin’s trip to Mar-a-Lago will, I think, turn out to be a key moment,” Cheney told me when we talked again this April. It would, she said, go down as one of the most shameful episodes in one of the country’s most shameful chapters. More than anyone, McCarthy ensured that the Republican Party would remain stuck in its 2020 post-election purgatory, still working to placate America’s neediest man.

Cheney, for her part, said she absolutely does care about the “legacy” question. “This is about being able to tell your kids that you stood up and did the right thing,” she told me last summer in Wyoming. In recent months, she has grown markedly uninhibited about expressing her dim view of her Republican colleagues. When commiserating with friends, Cheney sometimes invokes one of her idols, the historical biographer David McCullough, who has said that a great blessing of his work is that he gets to spend his days with John Adams and Thomas Jefferson and all of the other Founding Fathers. Cheney laments that she is not so lucky: “I have to spend my days with Kevin McCarthy.”

The scent of abandonment had been creeping into the Trump Hotel for a few years. First, the coronavirus ruined the business, and then the hotelier himself finished the job in November 2020 by doing something unforgivably off-brand: losing. It’s been a gilded ghost town in there ever since, populated by a smattering of still-Trump-obsessed sightseers from out of town, a few bored bartenders and stragglers, and Madison Cawthorn.

It’s a Waldorf Astoria now; the family unloaded the asset to a Miami investment firm for $375 million, well over $100 million more than the Trump Organization paid for it. The transaction illustrated an age-old This Town tradition: failing upward. What better monument to this era than this shunned and largely deserted property whose sale still turned a massive profit? And what better exemplar than a serially disgraced and unpopular former president who somehow remains the overwhelming favorite to be renominated by his party in 2024?

My final visit to the hotel, in February, coincided with the exact hour Russia was launching its invasion of Ukraine. It was one of those horrifically riveting news nights—flashes and explosions on TV and the sick mystery of what destruction might be concealed by the smoky darkness. Like Vladimir Putin, Trump will take what people let him take. He will do what he can get away with. The courage and character of Ukraine stands in perverse contrast to America’s cowering Republican Party, whose resistance might as well have been led by the Uvalde police.

It remains astonishing to me that, after everything we’ve been through with Trump and everything we’re still learning, he remains anything but radioactive in his party. My mind roils with thought experiments of what else Republicans could tolerate from him: What if Mike Pence had been hanged? One would hope it would have been disqualifying, but who knows? Right now, the two most likely people to be sworn into office on January 20, 2025, are Joe Biden and Donald Trump (requisite “to be sure” here about all the variables—age, health, jail sentence, etc.). Best-case scenario: Trump loses, his inevitable attempt to cheat the result is unsuccessful, and no one dies this time. And then America sails off again into the future with 109-year-old Joe Biden at the helm. Sigh.

Presidential candidates are always declaring that “the most important election of our lifetime” is at hand. In fact, this is usually true only for the person running. From here, though, 2024 does indeed resemble a genuinely fateful “time for choosing,” to use the old Ronald Reagan phrase. Trump could really win. In private, pretty much every serious Republican I know would agree that this would be a terrifying outcome. But in public, of course, it’s still a lot of “I will support the nominee.” Or, as Graham said flatly, “I hope President Trump runs again.” True-believer types like Representative Lauren Boebert of Colorado go even further; she declared recently that God himself had “anointed” Trump to be president. This, admittedly, might make him tough to beat.

Meanwhile, the number of elected Republicans willing to explicitly rule out voting for Trump remains tiny. Liz Cheney, again, has proved a towering exception. She says she will do everything in her power to prevent his return. She might be the foremost scourge in Trumpworld and could very well lose her Republican primary in Wyoming. But outside of that loud and devoted domain, Cheney has become one of the most admired leaders in America. She recently delivered speeches at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley and the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, receiving standing ovations in both venues and a Profile in Courage Award in the latter.

When I interviewed Cheney last summer, we talked about the nature of “existential threats” to America. Her father, the divisive former Vice President Dick Cheney, was always attuned to the enemies who might unleash doomsday scenarios (Russia during the Cold War, al-Qaeda and Saddam Hussein after September 11). Liz Cheney, who spent years studying and working in countries with autocratic regimes in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, has made it clear that she believes the primary existential threat to America today resides within her own political party.

I admit that I’ve been inspired by the handful of Trump-administration and state election officials who have testified before the January 6 committee. They have endured threats, smears, and constant intimidation in order to bear simple witness and perform their patriotic duty. In times like these, you learn to find hope where you can, in figures like Cassidy Hutchinson, the 26-year-old aide to Chief of Staff Mark Meadows whose earnest accounting of what she saw heaped so much shame onto the enablers of that horrific day. God bless her.

In contrast, you have Kevin McCarthy. He hates discussing 2024 on the record. Mostly because it involves talking about Trump. “Why do you keep asking me about Trump?” McCarthy said to me when I accompanied him to Iowa last year. It was as if the former president were sitting on his shoulder, watching for any sign of disloyalty. Whenever Trump’s name came up, McCarthy seemed to be bracing for an orange light fixture to drop on his head.

But it’s fun to make McCarthy squirm, so I asked him if he thought Trump would run again. He flashed me a look—not a nice one.

“I think he’ll talk about it,” McCarthy said, finally. “I don’t think he’ll make that decision until later.”

Did McCarthy want Trump to run? His look got even dirtier. “I think it’s a long way away,” he said. “I think there’s a lot of stuff that’s gonna happen prior to that.”

McCarthy will not be winning any Profile in Courage Award anytime soon. In fairness, that could make him a good fit for the cowardly caucus he is so eager to lead.

Soon enough, 2024 will not be a long way away, and Trump is well positioned to claim his third consecutive Republican presidential nomination. Again, Trump will do as he pleases and take what he can take. Because really, who’s going to stop him?

This essay is adapted from the forthcoming book Thank You for Your Servitude: Donald Trump’s Washington and the Price of Submission.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.