Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on hark

At Holman Correctional Facility, in Atmore, Alabama, the prisoners have a tradition of beating their doors when guards take a man from the holding area colloquially known as the “death cell” to the execution chamber to be killed. More than 150 men slam their full strength against solid steel, rolling thunder down the halls. It’s a show of solidarity with the condemned man—not because he is presumed innocent or absolved, but because the men of death row are uncommonly aware of death’s uncompromising egalitarianism. It’s coming for all of us, and they mean it when they say it.

Death came for Joe Nathan James Jr. on July 28 of this year, but the lethal-injection procedure that followed the prisoners’ last cage-rattling display of camaraderie stretched to roughly three hours, resulting in multiple needle-puncture sites and, eventually, what appears to have been a venous cutdown, or an incision into James’s inner arm meant to reveal a vein. (This is not, quite obviously, what is supposed to happen.) Yet in the immediate aftermath of James’s execution, John Hamm, the commissioner of the Alabama Department of Corrections, claimed that “nothing out of the ordinary” had taken place in the course of his killing, which might’ve passed for public knowledge had The Atlantic not published the results of an independent autopsy staged shortly after James’s death. I was there at the autopsy and saw for myself what they had done to him, all the bruised puncture sites and open wounds. I confess I had hoped the facts of what happened to James might prompt some hesitation among Alabama’s legislators about rushing to lethally inject another man. But no Corrections Department representative ever so much as responded to my questions, much less the substance of the reporting: The next execution date kept drawing nearer.

Thus that dreadful clanging boomed through Holman prison again last Thursday, September 22, at roughly 9:25 p.m.—less than half an hour after a lawyer known in death-penalty-litigation circles as “the death clerk” notified Alan Eugene Miller’s defense attorneys that the Supreme Court of the United States had rejected Miller’s final plea, allowing the state of Alabama to proceed with his scheduled execution. The notification, which soon reached attorneys for the state of Alabama and officials at Holman, began a roughly three-hour countdown to midnight, at which time Miller’s death warrant would expire, legally prohibiting the state from any further efforts to execute him until another warrant could be secured—something that takes at least a month’s time. The general public was made aware of the Supreme Court’s ruling at 9:15 p.m. It came down without any stated reasoning from the Court at all, along with a split: Amy Coney Barrett, a reliable conservative, had voted with Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson to stay Miller’s execution, pitting the Court’s women against the Court’s men.

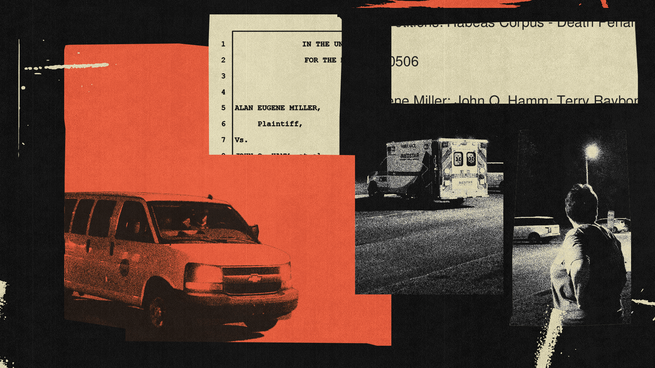

By the end of that surreal odyssey of a night, when Miller was suspended vertically from a cross-shaped table, hands and one foot bleeding in an execution chamber and the state of Alabama apparently realizing it wouldn’t be able to kill him within the time it had, Barrett’s dissent would seem wise, even prescient. But that would come later. Shortly after we heard the Court’s decision, those of us whom Miller had chosen to witness his execution—his sister Cheryl Ellison; brother Jeff Carr; sister-in-law, Sandra Carr; uncle Richard Carr; attorney Mara Klebaner; and me—gathered in front of the Wind Creek casino in Atmore, where the Alabama Department of Corrections elects to rendezvous with witnesses. We passed the time in strained banter until about 10:24 p.m., when a white Alabama Department of Corrections van pulled up in the casino’s pick-up lane, and a blue-uniformed guard emerged to direct us inside.

The strip of rainbow neon crowning the casino slumped below the black horizon in the van’s rearview mirror. As broad highway narrowed to country road, thick pine woods enclosed us, ringing with cricket and katydid calls. The van passed through gated checkpoints and razor-wire fences, orange floodlights scattering the shadows. The driver and a uniformed corrections officer who rode with him herded us through a guard shack outfitted with a metal detector, then took our phones and identification. A second van drove us a negligible distance up the gated road to the execution chamber.

At 10:30 p.m., two uniformed guards guided us, again, out of the van. This time we found ourselves in a cul-de-sac terminating in the high walls and slit windows of Holman’s death row. The squat building sat beside us, its heavy door cracking open, occasionally, startlingly, to spill light into the dimness. But no word came from within. And so we paced, and waited.

Jeff Carr, Miller’s brother, wandered alone, contemplative. I walked alongside him after a moment, and looked up into his face to find him chagrined, almost, to have tears in his eyes. All night, Miller’s family had carried on this way: good-humoredly, irreverently, and with flinty resolve—but always warm, never forbidding. Neither Alan Miller nor any of his family members have ever disputed that Miller shot and killed three people—Lee Holdbrooks, Christopher Scott Yancy, and Terry Jarvis—during a delusional episode in 1999 that, according to testimony heard at trial, caused Miller to believe the men had been spreading rumors about him. In fact, nobody in Miller’s family present that night registered a general objection to the death penalty—only to torture.

I asked Jeff if he was a praying man. He said he was, and that he’d been doing plenty of that. In the final days of a prisoner’s life, the Alabama Department of Corrections permits extended visitation with close relatives and a spiritual adviser, but the rules for their meetings are exacting. A prisoner’s family members may share a meal with him but aren’t allowed to eat food from the prison’s cafeteria or to bring in their own; instead, they’re permitted only the soda, candy, and packaged snacks in the on-premises vending machines, a requirement that had forced Alan’s younger brother, Richard Miller, and Jeff, each diabetic, to choose between getting sick or losing precious time with Alan to leave prison grounds to eat. They chose high blood sugar and nausea, and stayed with Alan as long as they could.

Standing beside Jeff outside death row, I spent a moment feeling despondent. Since my reporting in August on the last execution that took place on these prison grounds—the botched killing of Joe Nathan James—I have exchanged text messages with several people at Holman, both incarcerated and employed. I often begin my messages with a circle and a slash, like a person waving hello. I looked up and, high inside the prison, saw a man holding a sign: \o.

Earlier that day, I had sent an email to spokespeople for the Corrections Department, asking whether they had changed their execution protocol after James’s execution, whether they had trained their staff to establish venous access on a patient of Miller’s weight—350 pounds—and whether, in the event they could not, they planned to perform a cutdown in the prisoner’s arm, which is not permitted by their protocol, or if they hoped to perform a central-line procedure, which is. I wasn’t surprised that they hadn’t responded to me; they almost never do. In fact, because all of my efforts to serve as a media witness for the state’s last two executions had gone unanswered, I approached Miller with the idea of serving as a personal witness for him. Miller, who was by then well aware of what had happened to James, agreed; Richard Miller lent me his seat among the six spots reserved for Miller’s choice of family and friends.

I asked one of the uniformed guards for the time. He told me that it was 10:53 p.m.—and then, calmly, but suddenly, and without any obvious provocation, the two uniformed guards supervising us, who had recently been joined by a Corrections employee wearing a suit and tie, instructed us to climb back into the idling van, which we did, confused and querying. We were told to wait, and we stared through the back windshield at the men as they turned their backs to the van and talked among themselves, gesturing with their arms and rubbing their faces. In about an hour, Miller’s death warrant would expire. The blue digital clock on the van’s dash was wrong by an odd number of hours and minutes, registering the time somewhere around 9:05. We matched the false hour with the real one given to us by the guard and kept time. It was a hot night, and condensation gathered on the windows as we talked anxiously. Richard worried Alan might be fighting his captors. Sandra Carr, his sister-in-law, worried that he might be hurt. Nobody in their family has good veins, she said. Especially not Alan.

In the distance, more prison vans idled, their headlights hovering on the horizon. Another vehicle passed them with red and blue sirens flashing—Bizarre, I thought—and then a stripe of light from the execution chamber opened the night, and we were unloaded into the death chamber shortly before 11:30 p.m.

What followed resembled other executions I have witnessed so much that I was certain Miller was about to die. We were led by wordless guards into a small tiled area focused on an indoor window, which, when unveiled, would provide a one-way view into an execution chamber. The witness room was an oddly proportioned hexagon with cinderblock walls; a glowing rose-pink fluorescent fixture lit three rows of chairs. Signs posted on the walls instructed us to stay seated and be quiet. A blue hospital curtain hung on the other side of the viewing window, in which I could see the reflections of Cheryl Ellison, Miller’s sister; Jeff; Richard; and Sandra. Their faces were muted and downcast now, as they waited for the veil to be drawn aside so the state could kill their loved one. Behind us, two uniformed guards stood by the room’s only door, and a middle-aged woman in a pantsuit swayed between them serenely, her eyes closed, rocking on her feet as though she were in church.

Mara Klebaner, Miller’s lawyer, asked for the time. One of the uniformed guards said that it was 11:35 p.m., meaning that the state had by then had about two and a half hours to set an IV line in Miller, and it still wasn’t ready to open the curtain and begin his execution. What on earth had Alabama done to the man?

On the other side of the window, Miller, too, remained under the impression that he was about to die.

Miller later recalled having been strapped down to a gurney at 10:25 p.m. with his arms outstretched, under glaring white tube lights in the same dimensions as his cruciform table. He remembered how the guards took his glasses, and how a trio of men in scrubs appeared and began attempting—unsuccessfully—to establish access to his veins. (Alabama Department of Corrections did not respond to a request for comment on this or other details reported in this story.)

Miller said the men were gentle, and that he asked them casually about the gruesome struggle to set an IV line in Joe Nathan James as they pushed needles into his arms, hands, and a foot. They cut their glances and declined to meet his eyes, he recalled, until one huffed: “Don’t believe everything you read.”

Over the next 60 to 90 minutes, Miller said, the men stared at, stroked, and punctured his skin in hopes of finding a vein—even producing a pocket flashlight to try to detect a vein visually, and then accepting the offer of a plainclothes corrections officer’s cellphone flashlight, but to little avail. Every puncture evidently failed. At one point, Miller remembered the men putting a foam ball in his hand and asking him to squeeze it, which he refused to do. The overhead lights blazed, and personnel moved around the room. Miller couldn’t always monitor the clock. Eventually, one of the men began to tap on the veins of Miller’s neck.

Miller recoiled sharply. Though the state’s protocol permits an execution team to set a central line—a venous catheter often set in the neck or groin—in the event that venous access cannot be established normally, teams had been notably unable or unwilling to successfully set IVs in those locations in other recently botched executions.

At about half past 11, Miller heard a sudden knocking on one of the death chamber’s windows. Someone affixed a strap over his chest and jacked the table into a vertical position, and the three men who had pushed needles into him over the past hour-plus departed the room. Miller was left hanging off the upright gurney, his hands and one foot bleeding from failed IV attempts, waiting to die.

After about 20 minutes, he estimates, of Miller asking aloud what was happening to him in the empty silence, an ADOC employee finally answered him, somewhere around five minutes to midnight: “Your execution has been postponed.” The gurney collapsed backward, suddenly flat again, and Miller said he saw white light.

If we had known any of this at the time, it may have come as less of a shock when a guard cracked open the door to the witness chamber and said simply: “You may exit.”

Miller’s family was stunned. “What?” Cheryl asked, staring in disbelief at the man who was now patiently directing us to file out of the prison. They had not yet so much as laid eyes on Miller. How could it be over?

“It’s been called off,” the man said placidly. We were given to understand that the “it” was the execution, but the circumstances of its cancellation—and the fate of Alan Miller—remained entirely unclear. As uniformed guards rushed us back onto the van, Miller’s lawyer and his family demanded to know where Miller was, and whether he was still alive. The guards said they didn’t know.

As the van pulled out of the prison grounds, we noticed an ambulance parked adjacent to the execution chamber, which immediately caught the attention of Miller’s sister-in-law and his brother, each retired paramedics. They worried something terrible had happened to Miller, and that the authorities had decided to rush him to a local hospital instead of going ahead with the execution—which, in lieu of any other information, made as much sense as anything.

The guards shooed us out of the van and deposited us in the casino parking lot without any further explanation of the night’s events; we had no idea whether Miller was dead or alive. While Miller’s brother Richard and his uncle, Richard Carr, gathered with other family members waiting at the casino, his lawyer, Sandra, Cheryl, and I rushed to Atmore Community Hospital, the nearest medical facility to the prison. If Miller were the one in the ambulance, we guessed they would take him there.

At 12:31 a.m., I began using my iPhone to film as an ambulance pulled into the hospital lot where we were already waiting, with a white Alabama Corrections Department transport van trailing behind it. But instead of backing into the ambulance bay, the ambulance came to a halt in a hospital parking spot. Klebaner, Miller’s lawyer, glanced in the back and was shocked to see that the person inside was not Miller. A single Corrections Department employee emerged from the transport van and said they knew nothing about Miller’s whereabouts or condition, but offered to call her supervisor to try to find out. Meanwhile, a paramedic emerged from the ambulance to tell me I wasn’t allowed to film. Five minutes later, a caravan of Atmore Police Department SUVs pulled in and a quartet of officers appeared, saying they had been summoned to deal with “a commotion.”

Klebaner explained to the officers the rather uncanny situation we found ourselves in: unable to locate a man who was supposed to be dead by now, with no clue as to his condition, or how we might go about finding him. The police admitted to being as baffled as we were.

But I couldn’t figure out who had been so troubled by our presence as to call the police, or why. None of us was screaming or shouting, much less behaving aggressively. We were stranded in a hospital parking lot in the middle of the night, soliciting updates from inmates and other attorneys as they came by text message and Twitter. At 12:58 a.m., news finally arrived. Terry Raybon, the warden of Holman prison, pulled into the hospital lot in a white Dodge sedan and parked alongside us, rolling his window down.

Immediately Klebaner asked if Miller was alive.

“Yeah, yeah,” Raybon said. “He is in his cell.”

At the end of his conversation with Klebaner, Raybon rolled up his window, zipped into a parking spot, took a loud phone call on speaker, and tore back out of the lot. He had promised us a phone call from a Corrections Department lawyer, and within a number of minutes a call did come to Klebaner, though it illuminated little about Miller’s whereabouts or condition.

On the other end of the line was Mary-Coleman Mayberry Roberts, the promised attorney, who explained to Klebaner with pleasant briskness that “the execution was simply called off due to the time constraints resulting from the lateness of the court proceedings,” a claim similar to what Alabama Corrections Commissioner John Hamm said in a press statement around that time. Roberts repeatedly told Klebaner that “nothing went wrong.” Miller was indeed alive and well and in his cell, and that was all she intended to say.

In fact, she seemed annoyed to be on the phone, perhaps displeased by the implication that she or the Corrections Department owed any explanation to Miller’s family, who had just spent the past several hours in whiplashing states of hope, horror, disbelief, shock, and suspense. Confronted with such a suggestion by Klebaner, she clarified her purpose. “Ma’am,” she said, “we called you as a courtesy because we understood that y’all were at the hospital and worried that that was Mr. Miller. I was calling to let you know it was not, that he is safe, and that’s all the information I have to give you at this time.”

Klebaner insisted that she be allowed to meet with her client at the earliest opportunity, and pressed Roberts to commit to a time at which they could, at the very least, schedule such a meeting. But Roberts demurred, peevishly, advising her to call during “regular business hours” and schedule an ordinary attorney-client visit. “This is ridiculous and it’s not helpful,” Roberts finally snapped, hanging up with a curt “Good evening” only a beat later.

Commissioner Hamm would tell reporters that the ambulance that left the prison that night had nothing to do with Miller’s execution. The back of the ambulance never opened while we remained, puzzled, in the hospital parking lot, and no further Corrections Department personnel arrived as far as I could see, only the lone driver of the transport van. The only thing I understood confidently by the time we left was that the Alabama Department of Corrections very much wanted us to go.

What do you do the night you were meant to die? Miller would later say that when he was told that his execution had been “postponed,” he was unaware that midnight was approaching and still certain he would die, and that when the gurney had been suddenly jolted backwards, throwing him into a supine position, his vision had split open to the white light above, and he had believed for half a second he really was dead. But then they had taken the restraints off of him and several guards had helped him to his feet, explaining, finally, that the first ADOC employee had been wrong—that it was after midnight, that the state could no longer touch him, that he had lived.

Miller said that they never returned him to his old cell that night, but rather placed him back in the death cell after a trip to the infirmary, and that the guards brought him a plate of catfish, green beans, and potatoes from the catering spread they’d brought in for the employees working the execution.

At some point after midnight, guards gave Miller a phone and allowed him to call his attorneys and family.

The slot machines were still rolling at 2 a.m. when we crossed back through the casino lobby, numb and wordless under a river of gleaming red and golden feathers suspended and lit from above. We crowded into the hotel room where Miller’s brother Richard had placed him on speaker phone, and we listened to the voice of a man who had just survived his own execution.

On Friday, September 23, the day after he was scheduled to die, Miller was permitted an extended visit with his attorney via federal-court order, during which time his injuries were photographed. The following day, he was assessed by a physician. That same judge also ordered “personnel employed, contracted by, or otherwise associated with Holman, the Alabama Department of Corrections, and Alabama Attorney General’s Office” to immediately preserve all of their communications relating to Miller’s attempted execution, “including e-mails, phone calls, text messages, notes, or any other form of communication, written or otherwise.” According to Klebaner, “Mr. Miller will continue to vigorously pursue his rights in the ongoing litigation against Commissioner Hamm, Warden Raybon, and Attorney General [Steve] Marshall, as well as explore all legal options available to him.”

Their litigation could help illuminate why the state of Alabama has at least thrice proved itself incapable of executing prisoners via lethal injection in ways that comport with the law, its own protocol, and common sense. Robert Dunham, the executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, an educational nonprofit organization, told me that Alabama’s latest failure to carry out an uncomplicated execution represented an endemic problem.

“This is the third execution in the last five years that Alabama has botched by virtue of their own incompetence in setting IV lines,” offering Joe Nathan James and Doyle Hamm, who survived a 2018 lethal injection attempt in the state, as the two prior examples. “Each time, ADOC has denied the obvious and claimed nothing went wrong. They say they’ve followed their protocol. One of these things must be true: Either they’re unreliable, or their protocol is unreliable. Neither one is acceptable when a person’s life is on the line.” Hamm died of cancer in 2021. Miller thus appears to be America’s only living execution survivor.

His family, too, survived something—as did the families of Miller’s victims, to whom Governor Kay Ivey extended her prayers early Friday morning, after Miller’s execution had been aborted. They most certainly deserve her sympathy, but Miller’s family say they haven’t heard from the Corrections Department or any other state agency about a debacle that could have, at the very least, been handled with some trace of decency. “Our family was treated like we were guilty by association instead of being there to support a family member in his likely last hours on earth,” Sandra wrote to me in an email. On the phone, she told me she felt worn out, like she’d been “rode hard and put up wet,” an evocative southernism for a horse worked up to a sweat under the saddle. I could hear her warm, familiar fortitude, and the exhaustion grinding it down. She is right about what she said—I saw it firsthand, how the prison guards shuffled them from location to location without explanation for cause or delay, and how they were left to wonder for about an hour whether Miller was alive.

Miller’s murders were unspeakably wrong—none of his kin dispute that, nor did I ever hear them utter a word to suggest that he ought not be penalized. But neither could I justify, in my review of events, what they had been made to go through that night, at the mock execution of their relative. They were as innocent as anyone, as innocent as you.

Before Doyle Hamm died, he never faced another execution date. Miller may or may not face another night in the execution chamber. If his litigation against the state is successful, it could provide greater detail about a corrections department that appears to be suffering several simultaneous crises, which could, in turn, help other prisoners facing execution in Alabama challenge their own gruesome fate.

The next man doesn’t have much time. On Friday, the Alabama Supreme Court declared that in fewer than eight weeks, on November 17, Kenneth Eugene Smith will face his death at the hands of the state. He will presumably die, if Alabama gets its way, in the same chamber that last saw Alan Miller and Joe Nathan James. There is death, there are things worse than death, and, occasionally, there is salvation—and any of them could be in store for Smith.

This story is part of The Atlantic’s Inside America’s Death Chambers series supported by the Public Welfare Foundation.