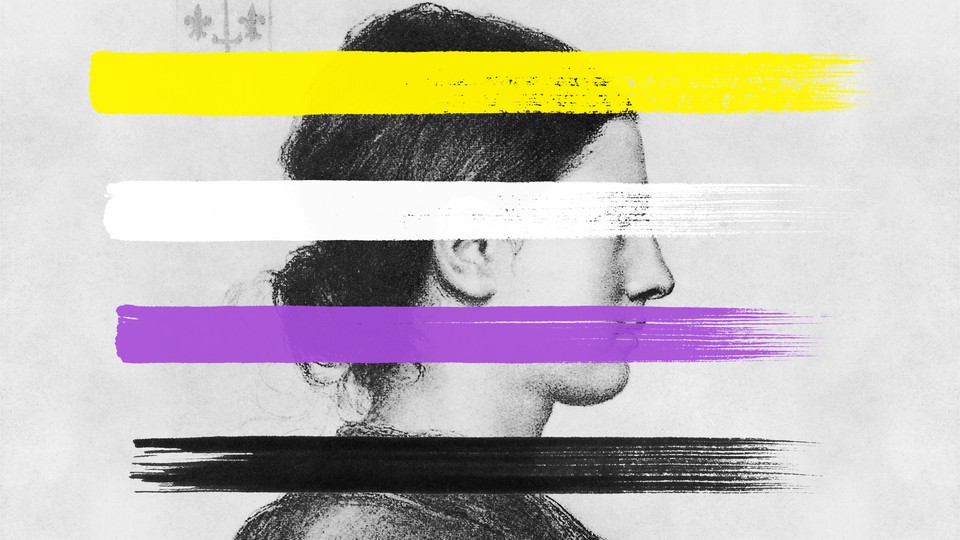

Does it matter if Joan of Arc was not a woman? “Our new play I, Joan shows Joan as a legendary leader who uses the pronouns ‘they/them,’” announced Shakespeare’s Globe theater in London on August 11. “We are not the first to present Joan in this way, and we will not be the last.”

That strange tone—half punk, half defensive—is more explicable in light of the backlash that followed. Many British feminists immediately objected that, yet again, well-meaning revisionists had deemed a historical figure too compelling to be a woman. “One of the consequences of the recent insistence that gender identity is more significant than biological sex has been the recasting of those who fail to meet the stereotypical standards of cis womanhood as trans or non-binary,” wrote Victoria Smith in The Critic, pointing to the author George Eliot, the Civil War soldier Jennie Hodgers, and the ancient Egyptian queen Hatshepsut, as well as Little Women’s Jo and The Famous Five’s George. “Whenever you find an interesting woman—or even just a woman called George—you should always consider the possibility she’s a man.”

Indeed, in I, Joan’s climactic scene, where Joan refuses to give up wearing men’s clothes, they give a rousing speech that concludes: “I am not a woman. I am a fucking warrior.” Excuse me? I spent my 20s arguing with stuffy conservative men who thought that women were unsuited to serving in the military. Does the bleeding edge of progressivism now agree with those dinosaurs?

The feminist argument against I, Joan’s gender politics is that nonbinary identities are an act of individual liberation that pushes the rest of us back into rigid pink and blue boxes. A few special rebels escape the stereotypes that everyone else is assumed to embrace. The response to this, from the nonbinary people I’ve spoken with, is that they/them pronouns simply feel like a better fit. The words fall on them, as Philip Larkin once wrote about jazz, “as they say love should, like an enormous yes.”

The fight over I, Joan was so bitter because everyone wants a piece of Joan of Arc. Suffragettes in England adopted her; so did their sisters in Ireland, who also saw Joan as a symbol of anti-colonial resistance. She inspired antislavery campaigners in America, but also Jean-Marie Le Pen’s hard-right French nationalists.

Today’s feminists want to claim her, arguing that very few women in history led an army. So do trans activists, who argue that very few people in history cross-dressed so openly, and suffered for it so obviously. “I’m always hungry for historical queer representation,” the play’s author, Charlie Josephine (who is nonbinary), told The Guardian earlier this week. “Because our history has been erased—particularly transgender people’s—there is very limited documentation of us throughout history, even though we have existed since the beginning of time.” The exact reasons for Joan having “her hair cropped short and round in the fashion of young men”—as the transcript of her trial put it—are therefore important, even if they are ultimately unknowable.

Going back to contemporary accounts doesn’t help, because these are conflicting: Joan is the only person burned at the stake who was canonized later, and her rehabilitation started within years of her execution. “Joan was using male apparel to appear sexless, rather than male,” writes her biographer Marina Warner in the introduction to The Trial of Joan of Arc. “She was not in disguise—everyone knew she was Joan la Pucelle, the magic virgin.” But the Bible forbade cross-dressing, and the Church elders refused to let Joan take Communion in breeches: “The men’s clothes she wore,” Warner writes, “became the burden of no less than five of the seventy articles in the charges of condemnation at the end of the trial.” Not long after, though, Joan’s body, desexed by both its appearance and Joan’s virginity, became central to her veneration. She had rejected the messy female body, and its association with sexual desire, childbirth, and breastfeeding. She was pure.

When the Globe announced I, Joan, the American right, sensing a culture-war opportunity, piled on too. “The fact that Joan of Arc was an actual woman is the whole point and what makes her story heroic and significant,” tweeted The Daily Wire’s Matt Walsh. “But then again, shoe-horning ‘non-binary’ characters into historical stories will always be clumsy and stupid because ‘non-binary’ didn’t exist until 14 seconds ago.”

In one sense, Walsh is right. The word nonbinary is new, as is the shorthand, enby, even if the concept is not. Those who identify as nonbinary are more likely to be under 29, urban, and white. A study by Pew Research found that people under 30 are three times more likely than the general U.S. population to report being transgender or nonbinary (pollsters treat the two categories as overlapping, as do many in the LGBTQ community). Last year, the 30-year-old singer Demi Lovato moved to they/them pronouns, because that choice “best represents the fluidity I feel in my gender expression.” But in early August, Lovato issued an update, explaining: “Recently, I’ve been feeling more feminine, and so I’ve adopted she/her again.” This is not how I understand gender: that your level of femininity goes up and down like the level in a gas tank, and you pick the pronouns to match.

Making Joan of Arc nonbinary is a legitimate artistic choice; asking questions about that decision is a legitimate critical choice. I am grateful to the Globe for staging this production—which I saw at the start of its preview period, before the production was finalized—and bringing this feminist conversation out from social-media silos and into the open. That’s exactly what a theater should do. All art is subjective: Josephine’s idea of Joan is no less valid than mine. We cannot possibly know what gender identity Joan of Arc would claim in today’s world—we’d have to explain the internet, the dishwasher, and Keeping Up With the Kardashians to her first. In 50 years, the prevailing categories might change again, and nonbinary may seem as outdated to future generations as hermaphrodite, invert, and molly do now.

The Globe’s statement argued, convincingly, that “theatres do not deal with ‘historical reality’ … We have had entire storms take place on stage, the sinking of ships, twins who look nothing alike being believable, and even a Queen of the fairies falling in love with a donkey.” However, this invocation of artistic license cannot extend to the production’s program, in which the academic Kit Heyam cheerfully claimed both Elizabeth I and the ninth-century English ruler Æthelflæd for Team Enby because the Tudor queen referred to herself—or “themself,” according to the essay—as a “prince,” and contemporary chroniclers describe Æthelflæd as “conducting … Armies, as if she had changed her sex.” Heyam claimed that “to take on a male-coded military role was, in some sense, for Æthelflæd to become male.”

Until recently, the consensus was that when medieval historians claimed it was unnatural for a woman to be brave or ambitious, the right response was: How sad that the past was so imprisoned by stereotypes. Not: Hmm, well, maybe they weren’t women.

A similar confusion was evident in the production’s content warning, displayed on notices outside the auditorium: This performance contains strong language, use of prop weaponry, violence, partial nudity, sexual references and misgendering. I was briefly confused: Would this be the bad kind of misgendering, which gets you banned from Twitter? Or the good kind of misgendering, when you arbitrarily reallocate historical figures to new categories based on stereotypes?

To understand how I, Joan came about, you need to know that the modern Globe was opened in 1997 as both a theater and a living museum. It is a replica of the theater in which William Shakespeare’s first actors played, and it stands in almost the same spot, on London’s South Bank, near the great dirty artery of the Thames. In aesthetic terms, its politics are conservative: Its previous artistic director, Emma Rice, departed over her desire to use artificial light and amplified sound, among other issues. In Globe productions, for an authentic Elizabethan experience, the actors are not miked. But the world moves on: Instead of shouting over the cacophony of hot-gospellers and bear baiters, they now have to bellow over the noise of planes flying overhead.

In ideological terms, however, the Globe’s politics are ultraprogressive. In 2019, it staged a well-reviewed production of Richard II, cast entirely with women of color, as well as a new commission titled Emilia, which suggested that Shakespeare’s talent was nothing compared with that of his lover, a Black woman poet called Emilia Bassano. “Times are finally changing,” reads the marketing material. “Not fast enough. It’s up to you. We are all Emilia.”

Reclamation is probably the single biggest trend in modern theater (and it’s pretty popular in film and television too). The emphasis is on “unheard stories” and “marginalized voices,” unearthing lost characters from underrepresented groups and putting them at center stage. That has run parallel to the practice of recasting white, male roles—which have always dominated theater—with actors from diverse backgrounds: Fiona Shaw played Richard II in 1995, Glenda Jackson played King Lear in 2016, and just before the pandemic, Ruth Negga played Hamlet in New York. We have this trend to thank for the Broadway super-mega-blockbuster Hamilton, which recasts America’s Founding Fathers as people of color. Broadening the talent pool by cross-gender and cross-race casting has made theater more exciting. At last, actors who are not white men are getting the roles that they deserve.

I too had always instinctively approved of the reclamation project, until I read Dava Sobel’s The Glass Universe, a book about the women astronomers of the 19th century, which was careful to note that its subjects were not ignored or forgotten. They were respected at the time, and valued for their skills, even if they did also face sexism. It is self-flattery to reflexively portray ourselves as rescuing them from obscurity and adversity. I had a similar thought in 2015, when a British newspaper asserted that the Star Wars actor John Boyega, the son of immigrants from Nigeria, had grown up on “tough streets” in crime-riddled South London. Boyega responded by tweeting: “Inaccurate. Stereotypical. NOT my story.” The desire to impose a struggle narrative on the experiences of women or people of color can sometimes be its own straitjacket. In the wrong hands, it can patronize the past and sound smug about the present.

Which brings me back to I, Joan. This is not a subtle play. It begins with the young lead actor Isobel Thom (who is nonbinary) walking onstage in a T-shirt that reads: PRIDE BEGAN WITH AN UPRISING. Thom’s first words are: “Trans people are sacred.” At the performance I saw, the audience applauded at this line, and I had the answer to my most pressing question: How would I, Joan deal with its lead character’s overt religiosity? The historical Joan claimed that her visions came from God. Her inquisitors (and Shakespeare, in Henry VI, Part I) thought that they were demonic and accused her of being a witch.

Instead of making Joan into a secular character, Josephine, the playwright, has leaned into the religiosity, making transness interchangeable with godliness. “We are the divine,” says Joan. Later in the play, Joan cannot see the trap that has been laid for them because people keep calling them “madam.” Joan’s god-given superpower is an acute ability to sense danger, but being misgendered is their kryptonite.

The unfortunate side effect of claiming divinity for the nonbinary is to depict everyone else as somehow lesser, a mere cis muggle. The dauphin, later king, is a posh man-child, bored and feckless. His male courtiers are starchy and pompous. His wife’s sole distinguishing characteristic is being pregnant. Her mother is a Hillary Clinton–esque girlboss who delivers dialogue like: “Isn’t it true, in this world of men, if you want something done, you hire a woman?” She then snaps open her fan. The audience whooped.

Joan doesn’t fit into this world. After the shy, lowborn courtier Thomas tells them that they cannot lead the army—“No offense, but you’re a girl”—they take a sword and cut off their mullet, strip to their boxers and chest binder, and put on a blue boilersuit. Is Joan going to lead the French army or fix its drains? Luckily, it’s the former, and they successfully break the siege of Orléans.

The ecstasy of battle delivers a revelation: “I hate this body I’m in … People think I’m a girl … I’m not.” Then, as if the playwright remembered that this might sound sexist, Joan quickly adds: “I love girls! I actually think I’m in love with girls … Girls are great. Nothing wrong with being a girl! Except if you’re not one.” In the middle of this defensive paragraph, surely written to fend off critics like me, Josephine does offer one beautiful metaphor, which I imagine will resonate with many people who feel uneasy with their body. Joan’s gender identity makes them a walking “civil war”—the bitterest kind—caught between a body and mind in conflict.

After Orléans, a few more battles follow, and Joan comes out to dependable Thomas: “I’m wordless, and it’s lonely, not having language.” When French soldiers turn up to ask if “she” is ready, Thomas replies: “They will be soon.” The crowd went “aww,” and the soldiers onstage accepted the update instantly. (Given their annoyance with the English occupation of Paris, they’d probably be up for a land acknowledgment or two as well.)

In the second half, of course, it all goes wrong. The newly crowned king is jealous of Joan’s popularity and annoyed by their stubbornness. His queen and her mother try to get Joan to put on a pink dress and marry a nice man, and Joan’s ingratitude prompts the mother-in-law to say, in exasperation, “You’re too much.” Joan replies: “Maybe you’re not enough.”

You can tell I’m getting old because my sympathies were largely with the queen’s mother here, trying to fill a power vacuum while delicately tiptoeing around her idiot son-in-law. Maybe this is at the core of the generational divide over gender? Punk—that desire to burn down the system, screw the pigs, smash it all up, and start again—is a young person’s game. When you get older, you make all kinds of grubby compromises in exchange for the English army not starving you out of your castle. The play works best when it gestures toward Joan’s youth, reminding us that they are a teenager. This is an underexplored part of the story: The closest thing the modern world has to a Joan of Arc is Greta Thunberg, an unearthly child sent to condemn the corrupt adult world.

That this play is at the Globe, the home of Shakespeare, only underscores that it is not in the Shakespearean tradition. The great English playwright is still revered today because he drove the possibilities of drama forward, creating characters with psychological depth and ambiguity. I, Joan is part of an older tradition, the medieval morality play. These pitted virtues and vices against one another for the soul of the protagonist: Greed and Sloth raged against Chastity and Patience. In I, Joan, that conflict has given way to one between Cisnormativity and Authenticity. I, Joan’s supporting characters exist not as people but as conduits for the moral lesson being delivered to the audience. “I hope you’re all watching so this shit don’t happen again,” Joan cries out in the second half. Soon after, Joan asserts that the “hardest pronoun to use is we,” which sounds like something Meghan Markle would say on a podcast.

That takes us to the climax, with Joan on trial, complaining about being put in a men’s prison before launching into a passionate denunciation of the clerical court and society at large. “Man tricked woman into hating trans,” Joan says, which again shows how ultraprogressive beliefs can shade into reactionary ones. Do women not have agency? Can’t they be bigots of their own volition? “The women are angry,” Joan continues, “about pronouns and toilets and Twitter and all the wrong things.” Well, Imma let you finish, but a major plot point not one hour ago was about you changing your pronouns, Joan. Also, yes, this woman is angry about toilets, having stood in line for the ladies’ during the intermission while the men breezed past into the urinals. (I’ll concede the point about Twitter being awful.)

Thom, in their debut professional role, commands the stage as Joan, and the direction is fast-paced and fluid, but the play’s tendency toward cheap laughs and agitprop overshadows moments with the potential to be intensely moving. After the trial, Joan recants their gender identity—“I’m a girl; I’m a girl”—thereby winning a brief reprieve from execution. But Joan cannot live a lie, and when returned to jail they once again cut their hair and put on overalls. Death is preferable to disguise.

Staged the right way, this could be as chilling as John Proctor’s famous speech in The Crucible as he finds himself unable to sign the document confessing to witchcraft: “Because it is my name! Because I cannot have another in my life! … How may I live without my name? I have given you my soul; leave me my name!” The most recent Crucible I watched had a female actor playing Proctor. It struck me that this speech could help the rest of us understand why trans people come out, despite the violence and rejection they face: because they want their name, their true name, to be recognized. How can someone live without their name? (Incidentally, The Crucible became the best dramatic interrogation of McCarthyism in postwar America by transposing its action to 17th-century Massachusetts; I suspect the best interrogation of modern identity politics will also come from an oblique angle.)

I wish I could have found The Crucible’s emotional depth, and empathy, in I, Joan. My sadness here is that Josephine and gender-critical feminists share a political goal, that of female liberation. Many of us, no matter our identities, can relate to Josephine’s admission that they had always wanted to play Mercutio, the flamboyant trickster, in Romeo and Juliet: “I’ve never really felt like I’m a ‘Juliet’ (whatever that means?) and always wondered why the lads get the best parts.”

The real Joan of Arc was part of this pattern. She dared to take on the traditionally masculine role of soldier and commander. In her day, everyone wondered: Was she holy—a saint, a sacred being, a vessel of enlightenment—or merely a woman? Four centuries later, the Globe is asking the same question.