The Rising Cost of Republicans’ Investment in Trump

GOP voters may be angry about Biden’s student-debt bailout, but the political bargain their party leaders made is the underlying problem.

Republican leaders and donors are suddenly making worried noises about their political chances.

Five months ago, their party looked likely to take both the U.S. House and the Senate in 2022. Republicans appeared ready to consolidate their leads over Democrats in the numbers of governorships and state legislatures held. Best of all, they seemed to have quietly sidelined former President Donald Trump.

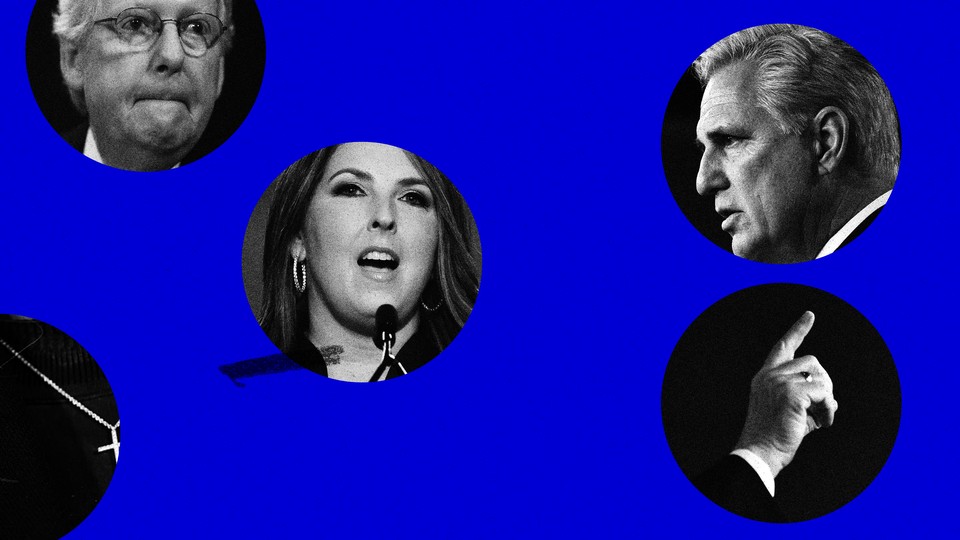

Now their prospects look clouded. Gasoline prices have dropped. The Supreme Court has overturned Roe v. Wade and galvanized pro-abortion-rights voters, including some nonreligious but otherwise conservative women who might have voted Republican. Their Senate hopes are being dashed because Trump intervened in primaries to nominate a bunch of unattractive candidates in must-win swing states. On Wednesday, Politico posted quotes from a very anxious conference call by Republican National Committee Chair Ronna McDaniel with major donors. Small-dollar donations to Senate candidates have dropped abruptly, even as Democratic fundraising surges.

Worst of all, from the point of view of Republican leaders, the enforcement of a search warrant at Mar-a-Lago has rallied tribal Republicans to Trump’s defense. The search boosted his fundraising to $1 million a day—and helped to extend his lead over Governor Ron DeSantis in a putative 2024 primary contest. NBC reported on a poll that showed Trump, pre-search, tied with DeSantis in a multicandidate field. Post-search, he led DeSantis 52–20. Although the Republican base loves Trump, Republican leaders recognize that he’s a general-election loser. Trump at the head of the ticket in 2024 spells trouble; even a reminder that Trump is at large in 2022 hurts down ballot. That’s why Republican leaders have pleaded with Trump to delay any announcement of a 2024 run until after November’s voting.

Biden’s program of student-debt relief can only add to the GOP gloom. One of the Democrats’ biggest difficulties heading into this election cycle was the lack of enthusiasm among younger voters. Earlier this year, only about 28 percent of voters under 35 expressed “high interest” in the 2022 election. That’s the same as in 2014, a year Democrats did badly, and far short of the 39 percent who expressed “high interest” at this time in 2018, a year Democrats did well. Now Biden has delivered big for voters with college debt. If they come out to reward him at the polls, they’ll provide a strong wall against any red tide.

Republicans are no innocents when it comes to preelection vote buying. In advance of the 2020 election, President Trump almost tripled payouts to farm families to offset the pain of his trade war with China, from $11.5 billion in 2017 to $32 billion in 2020. But Biden’s college-debt-relief program is far larger than Trump’s handout to farmers, adding up to at least $330 billion over 10 years, and possibly as much as $1 trillion.

The lesson for Republican leaders and donors is that sticking with Trump will be expensive. Trump himself and pro-Trump candidates are hurting the GOP’s election chances. Trump lost the presidency in 2020. Pro-Trump candidates cost the GOP its hold on the U.S. Senate in 2021. More pro-Trump candidates are slumping badly in 2022. More GOP stumbles mean more cash for Democratic constituencies.

Trump tried one exit from this predicament in 2021: a violent overthrow of his election defeat. That did not work.

Pro-Trump candidates in the states have tried other exits: rewriting election rules in their favor. That can work at the margins. But when something big happens—such as the overturning of Roe v. Wade—marginal gains may not suffice. To win consistently, a party needs a broad coalition. A party that keeps alienating great numbers of voters by nominating extremists, crooks, and weirdos is a party that is abdicating from governing. The costs of that abdication can be tallied in dollars and cents—as Republicans are tallying them right now. The National Taxpayers Union Foundation estimates that student-debt relief will cost the average taxpayer $2,000.

That’s only one line in the cost of Trump to the Republican Party and its voters. More bills will come in until Republicans accept that he and his faction will not disappear on their own. If they want to see the back of him, they’re going to have to grab him themselves and push him out the door with their own hands. If they don’t, their donors had better get used to more big payouts to more Democratic constituencies in the election cycles ahead.