What the Search-Warrant Affidavit Tells Us

The former president was not giving up top-secret national-security documents. DOJ had no choice but to act. Trump has only himself to blame.

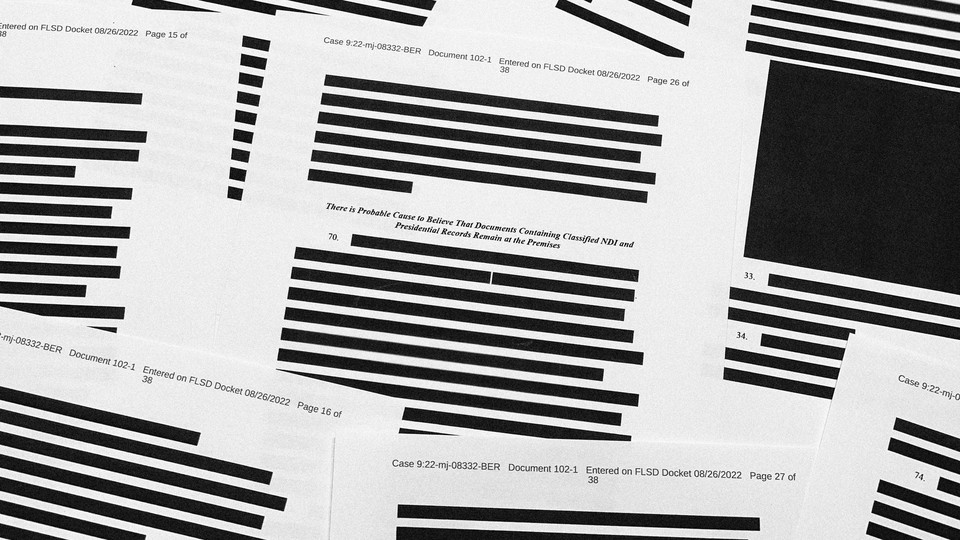

As I reviewed the heavily redacted affidavit relating to the FBI’s warrant to search Mar-a-Lago earlier this month, after its release today, I was reminded of the phrase from the Apostle Paul in his first letter to the church in Corinth that “we see through a glass, darkly.” Yes, we are able to discern certain things, but the whole truth remains hidden; we must thus approach the matter with extreme caution.

I’d compare the unredacted portions of the warrant affidavit to a case outline, a lawyer’s summary. We know the broad strokes of a potential criminal case against former President Donald Trump, and we know why the Department of Justice was alarmed by his conduct. But we don’t know the details, and in a potential criminal case, the details truly matter.

So here’s the basic story, as far as we can make out from the affidavit. On January 18, 2022, Trump provided the National Archives and Records Administration with 15 boxes of records. When NARA reviewed those records, it found “184 unique documents bearing classification markings.” Of those documents, 25 were marked top secret. Moreover, several of the documents contained quite specific “dissemination controls,” including—most notably—“HCS” and “SI” markings.

As the warrant explains, “HCS” refers to a form of “sensitive compartmented information” (SCI) that is “designed to protect intelligence information derived from clandestine human sources.” “SI,” which stands for “special intelligence,” refers to a form of SCI that is “designed to protect technical and intelligence information derived from the monitoring of foreign communications signals by other than the intended recipients.”

To put it plainly, information that contains HCS or SI markings is among our nation’s most closely guarded secrets. Indeed, when Trump handed them over, he provided evidence that he’d already potentially violated federal law by illegally removing national-defense information from its “proper place of custody.”

Because Trump handed over classified information, NARA contacted the Department of Justice. Interestingly enough, the affidavit describes how, the very same day that NARA informed Congress’s Committee on Oversight and Reform that it had found classified information in the former president’s records, a Trump spokesperson put out a statement on his behalf claiming, “The National Archives did not ‘find’ anything.”

At this point, however, the affidavit goes dark. Pages of redactions block sight of any additional details. Nevertheless, a few items of interest are still discernible.

First, DOJ very obviously did not believe that Trump had turned over all classified national-defense information (NDI) to NARA. One of the subject headings states that baldly: “There is probable cause to believe that documents containing classified NDI and presidential records remain at the premises.”

Indeed, news reports indicate that DOJ’s concerns were justified. On Monday The New York Times reported that DOJ had obtained additional classified information from Trump in June, and then seized even more classified information when it searched Mar-a-Lago earlier this month.

Second, DOJ also stated that there was “probable cause to believe that evidence of obstruction” would be found at Mar-a-Lago. These legal claims are not surprising. After all, the search warrant itself stated that it was based on evidence of violation of criminal statutes relating to improper handling of national-defense information and to obstruction of justice.

Third, the warrant affidavit notably mentions the claim by a Trump spokesperson in May that the former president had declassified the documents, and it includes a letter from Trump’s counsel asserting that Trump had absolute authority to declassify the documents. As the Politico columnist and former prosecutor Renato Mariotti noted on Twitter, “Typically defense counsel have very limited information about criminal investigations, and their views are not presented by prosecutors to the judge when seeking a warrant.” As a result, the magistrate judge in Miami knew of Trump’s legal objections yet granted the warrant anyway. This was not simply a matter of the judge taking DOJ’s assertions “on faith.” He reviewed both DOJ’s assertions and Trump’s documented objections. Crucially, Trump’s lawyer did not assert that Trump had turned over all relevant national-defense information.

What to make of all this? Here’s what the evidence indicates so far: Trump possessed top-secret documents; the Justice Department believed that he possessed them improperly and stored them improperly; Trump did not turn over all the classified material when asked; DOJ believes that evidence of obstruction exists; and DOJ knew about and disregarded (along with the magistrate) Trump’s declassification defense.

At the same time, we don’t know—and may not know for a long time—the precise nature of the classified materials. We don’t know who had access to those materials. And we’re almost entirely in the dark about the reasons DOJ asserts probable cause to suspect obstruction of justice.

This latter point is particularly important. The specter of the FBI investigation of Hillary Clinton haunts these proceedings. She was not charged after improperly storing classified national-defense information on a private server—including information classified at the same top-secret/SCI level as some documents located in Mar-a-Lago.

When then–FBI Director James Comey announced that his agency was not recommending a prosecution of Clinton, he articulated a prudential standard that he said had governed prior charging decisions:

All the cases prosecuted involved some combination of: clearly intentional and willful mishandling of classified information; or vast quantities of materials exposed in such a way as to support an inference of intentional misconduct; or indications of disloyalty to the United States; or efforts to obstruct justice. We do not see those things here. (Emphasis added.)

If that’s the prudential standard that was applied to Clinton, the same standard should be applied to Trump. This does not mean that he shouldn’t be prosecuted; it does mean that if DOJ chooses to prosecute, it should come forward with clear evidence of the exact misconduct identified above. The distinctions between Clinton’s case and Trump’s case would have to be transparently obvious.

Of course, the search-warrant affidavit was not released to provide public justification for prosecution. We’re a long way from knowing whether sufficient evidence exists to warrant a criminal charge. The affidavit was released—albeit in redacted form—to provide public justification for the search. Although we don’t yet know all of the evidence supporting DOJ’s unprecedented decision to search a former president’s home, we do now have much greater insight into the key facts.

Given that knowledge, the search looks less like a politicized witch hunt and more like an action of last resort—one the Department of Justice took only after it had tried and failed to obtain cooperation from the former president. The available evidence is pointing in one direction. Trump may be furious about the search, but he has only himself to blame.