A New Way to Think About Our Filing Systems

How we organize things affects more than just where they are: Your weekly guide to the best in books

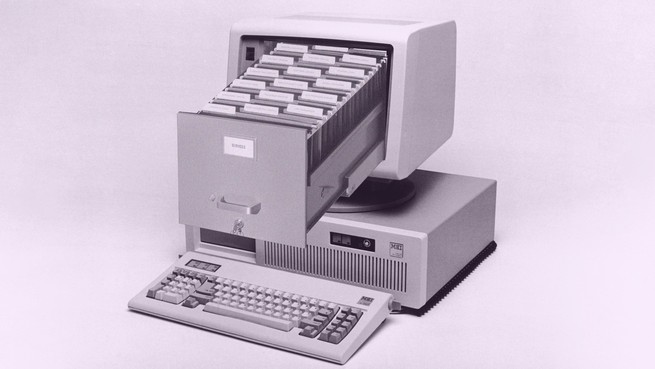

In The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information, Craig Robertson chronicles the history and influence of the titular 19th-century invention that revolutionized offices. The machine—for it was advertised as a piece of high-tech equipment rather than as a mundane furniture item—promised corporations a new level of capitalist efficiency. All company information could be quickly classified and stored according to a rigid system, and then just as easily retrieved.

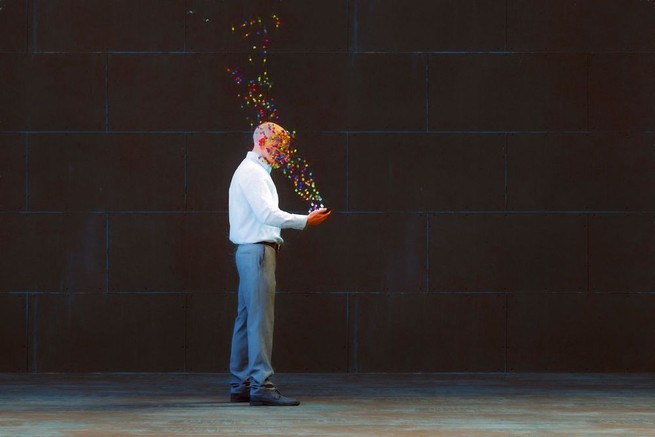

Of course, managing knowledge could never really be that simple. Today even computerized folders and advanced tools such as Google Search cannot tame the mammoth reach of our digital filing cabinets. This infinite sprawl is changing how we interface with the world, according to L. M. Sacasas, the author of The Frailest Thing. Sorting through this morass might seem too overwhelming to even consider—unless we shift how we think about the purpose of organizing information: What if the end goal was not efficient retrieval? What if, instead, the sorting process itself was imbued with meaning?

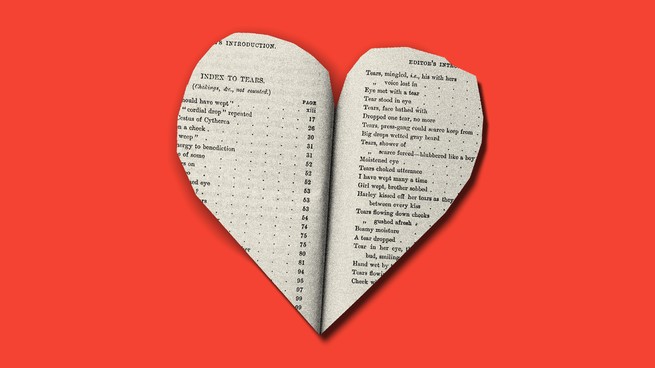

Take Roget’s Thesaurus. Its layout is meticulous. Yet its true power comes not from its utility as a tool of reference but rather from the awe its rich pages inspire: “a shimmering, unfolding, occasionally scarifying million-petaled experience, a miraculous nest of emergent relationships,” as my colleague James Parker described it. Book indexes can similarly be misunderstood as rote, but that view ignores their capacity for interpretation, whimsy, and intelligence, which Dennis Duncan explores in his book Index, A History of the.

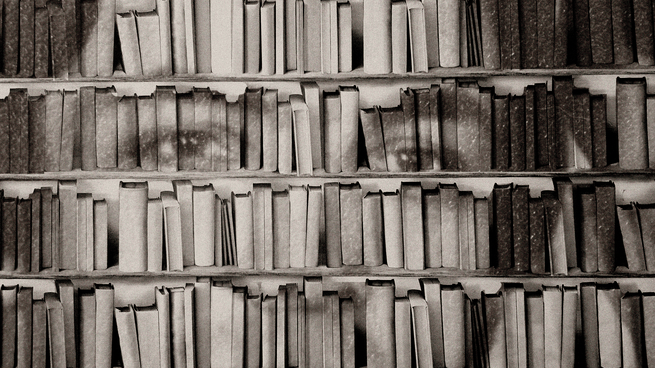

The writer Leslie Kendall Dye applies this spirit to the arrangement of her bookshelves. Their order follows no outwardly legible organizational principle; works are instead placed together “for companionship, based on some kinship or shared sensibility that I believe ties them together.” On her labyrinthine shelves, unexpected connections abound, tying together works such as Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince and Moss Hart’s Act One or Tennessee Williams’s Memoirs and Eric Myers’s Uncle Mame. The placements are at once a literary argument and a personal confession, revealing just as much about the arranger as about books themselves.

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

Bettmann / Getty; Tom Kelley Archive / Getty; The Atlantic

The logic of the filing cabinet is everywhere

“If the filing cabinet, as a tool of business and capital, guides how we access digital information today, its legacy of certainty overshadows the messiness intrinsic to acquiring knowledge—the sort that requires reflection, contextualization, and good-faith debate.”

Getty

Confessions of an information hoarder

“Infinite storage and effortless search changes our relationship to our information.”

Tim Lahan

“A thesaurus—here it comes—is for increasing one’s aliveness to words. Nothing more and nothing less. By going into the buzzing and jostling hive of words around a word, we get a purer sense of the word itself: its coloration, its interior, its traces of meaning.”

The Atlantic

The pleasures that lurk in the back of the book

“Indexes offer the reader multiple ways in and through the text, freeing them from the confines of an ineluctable narrative.”

Getty; The Atlantic

The organization of your bookshelves tells its own story

“The complexity of the human heart can be expressed in the arrangement of one’s books.”

📚 Act One, by Moss Hart

📚 Memoirs, by Tennessee Williams

📚 Uncle Mame, by Eric Myers

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Kate Cray. The book she’s reading next is I’m Glad My Mom Died, by Jennette McCurdy.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.