Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on audm

The text message came a little before 5 p.m. It was August 26, 2021. Eleven days earlier, the Taliban had overthrown the Afghan government. My friend—a German writer and academic—had been trying to help my family flee the country. Now she told me she had gotten my two younger sisters and me on the list for a flight to Frankfurt, a last-minute evacuation negotiated by the German government and a nonprofit group.

“What about my mom?” I asked. She didn’t reply for a moment. “I was not able to get her on this flight,” she answered. Please, I begged her: “My brothers are gone and my father is living with his second wife. She just has us, no one else, for God’s sake please do something.”

But there was nothing she could do. “These are the names that they offered me,” she wrote. “I know it’s a terrible choice.”

She said we had 20 minutes to decide whether to stay or go. We would need to pack, then take a taxi to a secret location, where we’d meet the buses that would drive the evacuees to the airport.

Just a few weeks earlier, my life had been relatively normal. We knew the Afghan National Army was getting weaker—on the battlefield, scores of soldiers were dying—and the front lines kept getting closer to Kabul. And yet, inside the city, schools, offices, and cafés were still open. People were going out to sing and dance; music played in restaurants and taxis. I was 21 and had recently started working for a newspaper, which had me traveling around the city reporting. I loved writing about people, especially the poor, whose voices were rarely heard. I wrote about how they lived, the problems they faced, the joy they experienced regardless.

My father is from Tolak, a remote district in Ghor province, where, even after the fall of the Taliban 20 years ago, women were still flogged and stoned to death. As far as I know, there has never been a journalist from Tolak, certainly not a female one. I knew that the life I was living would not have been possible if my father hadn’t worked hard to bring our family to Kabul. I knew it would not have been possible if the Taliban had remained in power.

But now the Taliban were back. On August 15, the government collapsed, the security forces disintegrated, and the president, Ashraf Ghani, fled. Once he’d left his people behind, Europe and the United States abandoned us too. If I could meet Ghani today, I would have nothing to say to him. I would silently stare into his eyes so that he could feel the homelessness of a young woman.

I had heard about the Taliban all my life. But I had never actually seen a Talib before. Suddenly they were everywhere, patrolling the streets of Kabul. My family gathered in my mother’s apartment, near the U.S. embassy: me, my younger sisters, and our mother, as well as our father and stepmother and their five kids. When the government disappeared, my job at the newspaper disappeared too. It wasn’t safe to commute to work anymore, anyway; none of us left the apartment except to go to the food shop just downstairs. The apartment was crowded. But we were together.

Now, suddenly, I had to choose between my loved ones. How could I leave my mother alone? If one of us girls stayed behind, which one should it be? What if the sister who stayed was killed? What if the sister who tried to escape was killed?

We sat on the floor of my small bedroom with its red-and-white curtains and tried to talk about what to do—me; our mom; my youngest sister, Sara; and another sister, Asman. I knew that my family would be targeted—I had two older brothers who had worked for the Americans and had already been evacuated, and I was a woman with a job. But I didn’t want to leave, especially when I looked at my mother’s face, at the lines across her forehead, her white hair that made her look older than her five decades—proof of how hard the life of an Afghan wife and mother is.

In the end, she decided for all of us. “You and Sara go,” she said to me. “Asman and I will stay.”

Sara was only 16 then—she’s a dreamy girl who likes adventure and wants to be a pilot when she grows up. My mother felt she wasn’t brave enough to adapt to the oppressions of life under the Taliban. Asman was 19. She is the quietest of us sisters but also the kindest. We’re two years apart but grew up like twins. She’s more than a sister to me—my all-time secret keeper. My mother knew she would be strong enough to withstand whatever came next. It was the best choice she could have made.

But what about me? I didn’t know how I would take care of Sara on my own. And how could I leave my best friend? (Asman, for the record, is a pseudonym; because she remains in Afghanistan, it is not safe to use her real name here.)

Sara and I packed a bag each, and my mother handed us some snacks—cakes and cookies—and water. We put on long black dresses and veils over our hair. I couldn’t look Asman in the eye. I didn’t have the courage to tell her goodbye. All of us were crying. As Sara and I walked out the door, my mother sprinkled water on our backs—an Afghan tradition to wish someone a safe trip. It all happened so fast. My father was sleeping in the other room. Instead of waking him, I just opened the door and looked at him—this brave man who had worked for years in the most dangerous provinces to support us and make it possible for us to go to school and have a better life. And then we were gone.

Related Podcast

Listen to Bushra Seddique tell her story on the podcast Radio Atlantic:

It was about a 15-minute drive to the buses. I felt like time stopped in those 15 minutes. Everything outside the window had changed; my whole country had changed. The taxi drove by a Talib, one of the first I’d seen up close. He was a young man in his 20s, wearing traditional Afghan clothes—all in gray, with the black vest we call a waskat and a black lungi wrapped around his head. His long, greasy hair fell over his shoulders and his eyes were dark, so dark that he must have been wearing surma—the sooty eyeliner that some believe improves vision and looks pious. He held a rifle.

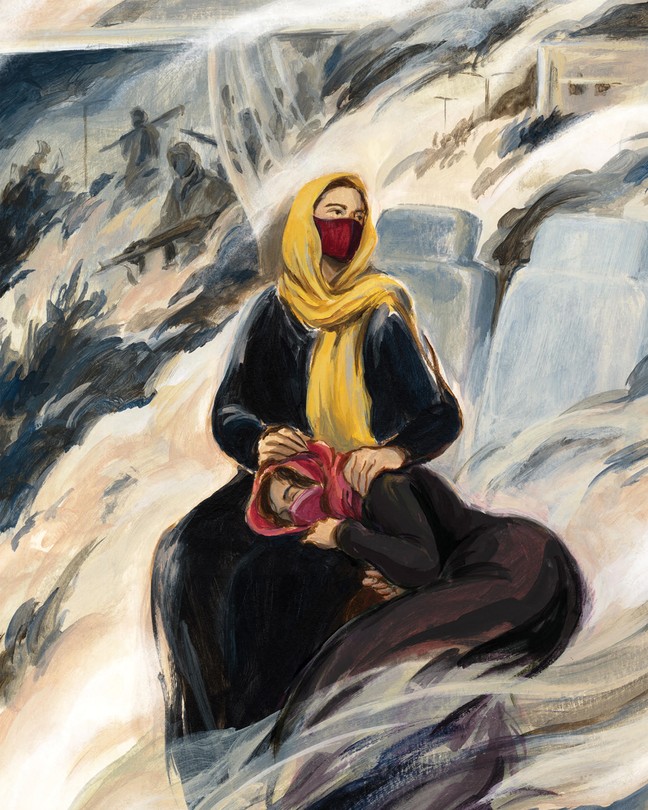

Now I could see the white flags of the Taliban and the gunmen everywhere, with their Humvees and motorcycles. I didn’t see any women or girls on the streets. I held tightly to Sara’s hand. I was her guardian now; I was her mother and her father. If something happened to us, it was my responsibility.

We stopped at the side of the road, where five buses were waiting, along with about 250 Afghans, including journalists, human-rights activists, and people who had worked for the German government. Someone was calling out names from a list, telling people which bus to get on. I went up to him—his name was Jordan, I later learned, and he was an Australian filmmaker who had reported from Afghanistan for several years—and asked about my mother. Was there any way to add her? Maybe it wasn’t too late; maybe she and Asman could still join us. “I am so sorry,” he told me.

Everyone else had a brother or father to help them with their bags and to keep them from being crushed by the surging crowd. Everyone was jostling to get on the bus first. But not Sara and me. When our names were called, we moved slowly. We still weren’t sure whether to stay or go.

While we waited on the bus, the sun set and the sky turned dark. We were told that there were a few things we needed to know. The first was that the airport was dangerous. It was under the protection of Taliban gunmen and American soldiers—for another four days, before the Americans left forever. If something happened to us there, the nonprofit group couldn’t take responsibility for it. Second, we were not allowed to turn the bus lights on. Third, the women must stay covered. At last, the buses started moving. In half an hour, we thought, we’d be driving through the gates and taking off into the sky.

But that’s not what happened.

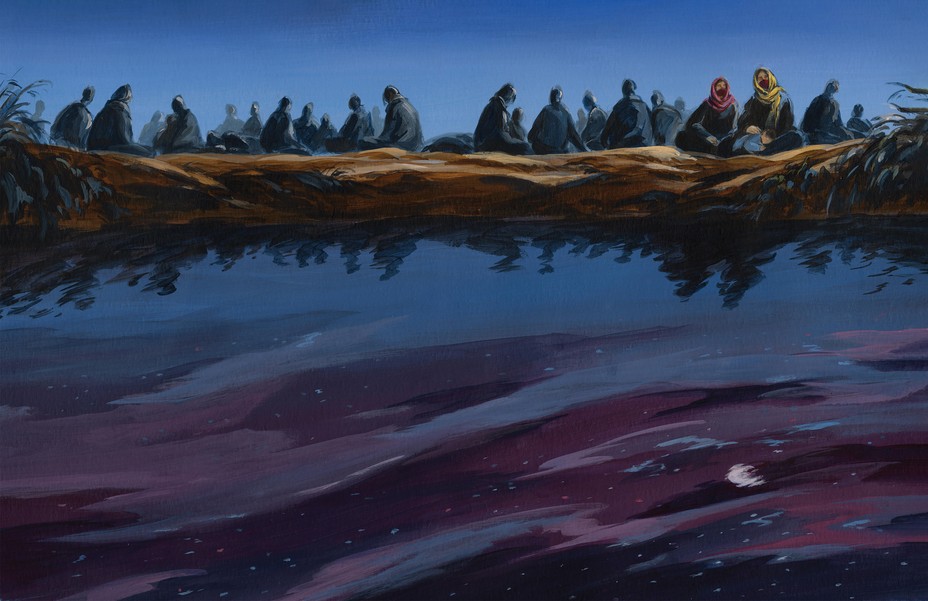

This wasn’t Sara’s and my first time at the airport; two days earlier, my family had made our initial attempt at evacuating.

Our older sister’s husband works in Canada, and we had applied for Canadian visas. The Canadian government contacted us to say it could fly us out of the country. We rushed to the airport and waited all night outside the Abbey Gate entrance. Thousands of people were sleeping on the dirt outside the airport, near a pond that was slowly filling with urine and feces and garbage. Finally, we saw some Canadian soldiers, but they were on the other side of the pond. To reach them, we’d have to wade through the sewage. So that’s what we did.

The soldiers let my older sister and her 5-year-old son through the gate, but I didn’t have all the documents the rest of us needed. My sister turned back to look at me, her face filled with guilt, but I tried to smile at her, and waved her on. She and my nephew, at least, would be free and safe. Then I waded back, soaking and stinking, and went home.

Today, as we returned to the airport, I realized that in many ways it was harder to be the sister who left than the sister who got left behind.

This time we were headed to a different entrance—the North Gate. The scene ahead of us was even more chaotic than I remembered. We heard an explosion and gunshots, and I saw fire on the horizon. Not long before, we learned, a bomb had exploded at the Abbey Gate, killing more than 150 people. The bomb went off right where my family had been sleeping just two nights before.

The attack was carried out by an Islamic State suicide bomber. He had been in a high-security prison, and was released when the Taliban set their own fighters free. It was a reminder that while the Taliban may know how to wage war—they’ve had decades of practice—they have no idea how to govern a country and protect the people.

Because of the bombing, the Taliban said it wasn’t safe to let anyone else into the airport. They turned the buses away, and we pulled over on the side of the road. Inside the bus, we were silent. But all around us, people were running and screaming. I felt like I was watching a movie about a war. But it was real. I wondered if I knew any of the people running, if my cousins or teachers were among the dead.

My mom called me, crying. She’d heard about the bombing and was terrified. She said we should give up and come home. But I didn’t want to lose our chance to get out. And besides, the only thing that seemed more dangerous than staying on the bus right then was getting off it.

The second day dawned quietly. No more gunshots, no more people fleeing. Most of our food was gone. Sara had fallen asleep lying across my lap. She had not once complained, and I was proud of her. Late in the night, I had texted my friend who’d gotten us on the evacuee list to ask if she could find out any more information. I wrote, “I don’t want to die.”

The passengers were all waking up now, their backs and knees aching. There were no bathrooms on the buses, and everyone was insisting that we needed to find a safe place to get off. The organizers conferred and decided to drive to a nearby university. It was empty except for a single guard, who allowed us to come in one at a time to use the bathroom and stretch our legs until the drivers called us back. My friend texted me, “There is movement.”

We returned to the airport, creeping slowly through the crowds of people and cars and other buses. Finally we approached the gate. We watched through the windows and tried to hear what was being said. We supposedly had permission to enter, but the Taliban guards weren’t letting us through. They feared another attack and were afraid for us or suspicious of us—or maybe both. Finally, a commander arrived and delivered the verdict: He wouldn’t let us in unless the Americans approved our entry themselves. The Taliban were in charge of guarding the outer checkpoints and the Americans were deeper inside the airport. We knew that they weren’t about to come out into Taliban territory.

We tried four more times, and each time we were turned away. Sometimes the guards would check our documents, sometimes not. By now we were out of food and water. “Bushra,” my friend wrote again, “how are you holding up? It has been so long!”

I told her I was thinking of getting off the bus, and she told me, “I cannot make this decision for you, Bushra. I also want you to live … I want you to live a safe and happy life in a place of your choosing.”

It was now our third day on the bus. We were trying to approach the airport again when two Talibs stopped us and came aboard. They wore the traditional waskats, but underneath they had put on the boots and camouflage pants that the soldiers of the Afghan National Army had once worn. Their faces were covered, but I could tell these weren’t just any Talibs; they were commanders. Their bodies were bigger; their guns were bigger. I thought to myself, You are done, Bushra.

“Why are you leaving the country?” they asked us. “Stay with us to make an Islamic government.”

Soon after, we got word that the Taliban were shutting down all the gates and blocking the road. Jordan told us we were out of options. It was time to give up.

“It’s over?” I texted my friend. She replied, “It’s over.”

We were starving and exhausted. I was a journalist and a woman stuck in a country now ruled by terrorists who hated journalists and women. The Taliban had a list of everyone who had tried to flee on the bus; they knew my name, and nothing would stop them from coming to knock on my mother’s door. I knew I had no rights, and no future.

And yet I was happy. It sounds crazy, but it was seven in the morning and we were going home. Sara and I got off the bus and into a taxi, and talked about what we would do first: eat or sleep. I said sleep; Sara said eat. “Are you happy?” I asked her.

“I am so happy. Maybe they are sleeping now; what do you think?”

“I think so. A good time to surprise them.”

We rushed up the stairs to our apartment, and Asman opened the door. “I knew you were coming back!” she said. We hugged one another tightly and laughed so loudly that we woke our mother up. We all four wrapped our arms around one another, and they told us how frightened they’d been. Then my mother bustled off to cook us a celebratory meal and I went back to my bedroom with the red-and-white curtains, fell onto my own soft mattress, and slept.

I slept until evening, when my phone woke me up. It was my friend: “Open your WhatsApp and read my messages NOW.” I saw one with the subject line “URGENT.” The gates were open again—the evacuation was back on.

We had to get back to the buses.

I got up and pulled on the long black dress and shouted for Sara. Asman said our mother had made quabili palaw—rice with raisins and lamb, my favorite. But there was no time to eat it. There wasn’t even time to say goodbye to our mother; she had gone to run an errand. She wasn’t there to sprinkle water on us as we walked out the door. But our dad was there. He brought out the Quran and asked us to pray. We recited some verses from the Fatiha, asking Allah for a safe journey—for him to “guide us to the straight path.” Then we kissed our father’s hand and he kissed our cheeks and heads. And for a second time, we left our home behind.

The Taliban had a new rule: no luggage. You were allowed only a small, clear plastic bag, so they could make sure no one was carrying weapons. Only a few of our clothes fit, and what about my laptop? All of my photos were on it, memories from childhood and university, and all of my writing—drafts of so many articles I was working on and wanted to finish. How could I go to a new country as a journalist without a laptop to write on? I had only $400 in cash to last through the journey and whatever came after; I couldn’t afford a new computer. So I tucked it under my dress and hoped no one would notice.

This time everything moved much faster. We passed through a checkpoint on the road. Waited a few hours. Then another checkpoint. A rumor was going around the bus that the Taliban would turn back any woman traveling without a male guardian. When we heard that, Sara and I lost hope again. But I had an idea. I asked the kind family sitting behind us if they would say we were their cousins, and if the husband would pretend to be watching over us. At first he said no—he didn’t want any trouble—but his wife persuaded him to help us.

It was our turn at the gate. We got off the bus and the guards separated the men and women into two lines. They checked our bags, and then a Taliban commander called people up one by one. We were so afraid they would know that we had no man with us, but in the end no one even asked. Finally we were inside the gates.

It wasn’t how I had pictured it: The place looked more like a military base than an airport. Behind us were the Taliban gunmen. Ahead of us were the American soldiers. My little group of evacuees stood between them. It seemed impossible that these armies that had fought each other for almost 20 years were now just standing there, sharing the road. America had promised to fight the terrorists, but it handed our country over to them instead—trading us for its own convenience. It felt like a great betrayal.

And yet I could see that the individual American soldiers were doing as much as they could to help us. As we entered the American side of the airport, I saw them bringing people water and snacks, being kind and smiling at kids. A few soldiers were lying in corners, fast asleep. They were clearly working hard to get as many people to safety as possible. It made me wonder where all the Afghan soldiers had gone when they surrendered. Why weren’t they helping their people?

The first thing Sara did was tear off her long black dress and say she hoped she would never wear such a thing again. I kept mine on because it was hiding my laptop. We were thirsty, but there was no water—only cartons of milk, for children. We drank a few each. I texted my friend, “We are in,” and sent her a selfie of Sara and me. She wrote, “Yessss!!!!”

Now the Americans had yet another new rule for us: no luggage whatsoever. I took my favorite shirt and pair of pants out of my bag and changed into them. Sara, who loves fashion, hated to give up her clothes. We left them all in a pile. I held on to my passport and other documents, a photo of my father, my mother’s watch, and my laptop.

The sun was rising and we were weak with hunger and exhaustion. For four hours we stood in line until we reached a checkpoint where soldiers examined our pockets, our folders, even our hair. When my turn came, I said I was a journalist and begged them to not take my laptop. They made me turn it on, to ensure it really was a working computer, and to my enormous relief, they let me keep it. It was late morning now, and the soldiers brought us water bottles hot from the sun. Each of us was given an identification bracelet. I didn’t know it then, but I would wear that bracelet for the next four months.

It had been almost three full days since I’d gotten that first text message from my friend about the flight. In that time, we’d traversed just two and a half miles. And now I was about to travel across the world. I was heartbroken to be leaving my mother and sister, relieved to be free of the Taliban, but also furious at the United States and the world for abandoning my country. What would happen to me? What would happen to everyone I left behind?

It was 11:30 a.m. on August 29, the day before the last American soldier left the country. Five hundred of us evacuees flew in a military aircraft, a C-17. I had never flown before, and I wouldn’t have predicted that my first time would be on a military plane with no windows, sitting on the floor, escorted by soldiers.

I asked Sara, “Are you excited?” I could tell she wasn’t thinking about the Taliban or our mother or the past few awful days. She was thrilled. She pointed to an American soldier—a woman—and said she looked very brave. “I want to be a pilot in the Air Force,” she told me, and I said, “Yes, you can!” But when the plane took off, every single one of us—even Sara—wept.

We landed in Qatar, where we met with some American officials. We explained that our brothers had worked for USAID, and they gave us permission to travel on to America. Many evacuees had to stay in Qatar for a long time, but because we were young women traveling alone, I assume, they put us on one of the first flights out.

We stopped in Germany, and finally, on September 4, Sara and I landed in Washington, D.C. From there, we traveled to Camp Atterbury, a military training post in Indiana. I’d never heard of Indiana before. Winter began and it was cold; I’d never experienced a cold like that before. We spent much of our days waiting in lines for meals, and by the time we finally got inside, our faces would ache from the wind and our hands would be so frozen, it hurt to bend our fingers. Thousands of Afghan evacuees lived in the camp, and Sara and I slept in a big room with 40 other people, including babies who cried at night. We were safe, but it was like living in a prison.

While we were at the camp, Sara and I were reunited with our oldest brother and his wife and three kids. And at the end of December, we all moved to Maryland, to a three-bedroom apartment near Washington, D.C. Our place is small and noisy, but happy. Sara is going to high school again. She’s learning to ride a bike and applying for a part-time job at the library down the street, which I use most days as an office. I found work as a journalist—an editorial fellowship at this magazine. What we are doing now, the Taliban would never let women and girls do.

When I talk with my mother, she says she misses us; she says the apartment is too quiet now. When I talk with Asman, she says she is lonely; I am no longer there to irritate her by eating all her leftovers and messing with her long hair. She has no one to dance around the room with, no one to plan her future with.

I wonder sometimes: What if I had stayed and fought for my country? The Taliban prevented my mother from getting an education the first time they were in power, in the ’90s. Now they are back and doing the same thing to Asman. The Taliban have banned women from traveling without men, from participating in sports and the arts, and from doing most jobs. When outside the home, they must cover themselves from head to toe. The Taliban are hunting down and killing people who fought for the old government. The economy has collapsed, and children are starving.

No one is left to chronicle how Afghans are paying the price for the Taliban’s victory. Activists are arrested, and journalists are forbidden from reporting the truth. It is hard to be an exile, but it would be harder still to be silenced. I smuggled my laptop past the Taliban and carried it across continents to a free country so I could write this story, so I could tell you this.

This article appears in the September 2022 print edition with the headline “My Escape From the Taliban.”