The Power of the Black Portrait

Visual art can help restore dignity to those who have been dishonored.

On Sunday, I visited the Mariposa Museum in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts. They are showing an exhibition of the work of the Senegalese fine-art photographer Omar Victor Diop. I’d written a catalog essay for him, and so I was eager to see the work again. Though I’m untrained in art history (beyond a few college courses), I love to write about visual art. In particular, I love to write about the work of artists who use the visual as a historical archive, and even more so if what is represented includes a palimpsest of artifacts. Diop takes photographs of himself embodying historic figures of the African continent and diaspora. In one, he is a member of the Black Panther Party; in another, he’s Dutty Boukman, an early leader in the Haitian Revolution and a Vodun spiritual leader—a houngan—from the Senegambia region of West Africa. In one piece, repeated images of Diop represent railroad workers striking in South Africa; in another, formerly enslaved people who created a Maroon society in Jamaica. As Frederick Douglass, he dons a thick mane of kinky hair. Attire and accoutrements tell the figures’ histories.

I also took in the work of Mario Moore recently, this time on Instagram, though I’ve had the good fortune of seeing his work in person many times. Mario’s work is always deeply historically and politically informed and grounded. This week I watched as he sculpted a stunning bust of his wife, filmmaker Danielle Eliska Lyle, and worked with his mother, fine artist Sabrina Nelson, on a silverpoint drawing of the abolitionist Sojourner Truth. Silverpoint preceded graphite—it was the pencil of the old masters—and so its use gives works a feeling of historic gravitas.

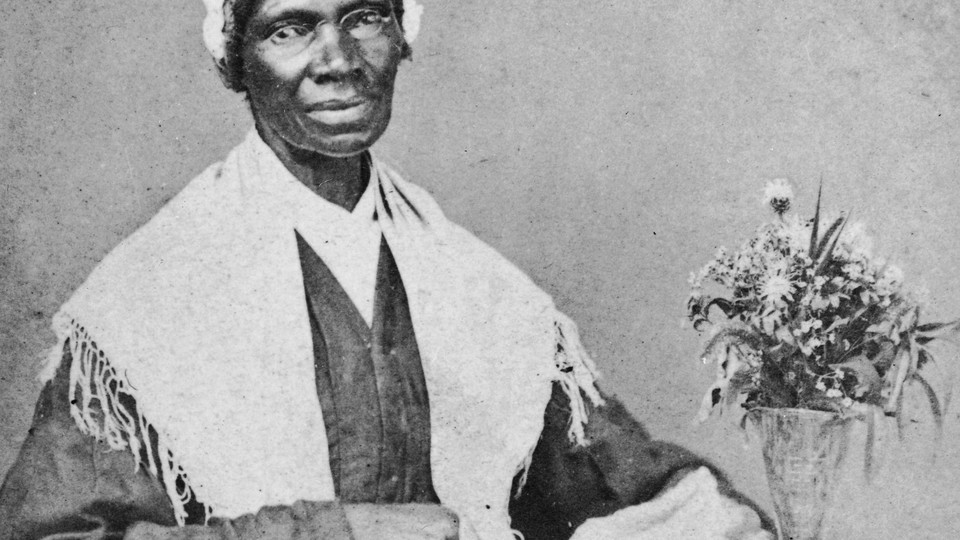

Truth’s biographer, the august historian Nell Irvin Painter—who is now a working fine artist—made a point about Truth that stuck to my bones the first time I read it: Truth was illiterate. All of the quotes attributed to her were mediated by white interlocutors. And given that they often reported Truth as speaking in Southern vernacular even though she was a Dutch-speaking native of New York, we should read those words with more than a grain of salt. But, Painter noted, we can read her in another way, too: through her self-fashioning image. She sold cards with her likeness, with Truth wearing a white bonnet and shawl, her knitting in hand, and text that read, “I sell the shadow to support the substance.” Her fellow Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass was the most widely photographed man of the 19th century, but he also left a trove of written words. Truth did not. Her images stood as a way to tell her story. When I wrote a bit about Truth, I was awed to learn that she successfully lodged a lawsuit against a man who illegally sold her son into slavery in Alabama. Behind her image is a story of extraordinary brilliance that demands to be recounted.

This stream of encounters over the past week has made me think about inheritances that are not economic, and that come with not only a history of degradation but also of dignity.

In 1998 Harvard held a special convocation to award Nelson Mandela an honorary degree. At the time, Harvard had held only two other special convocations, one for George Washington and another for Winston Churchill. Mandela’s journey from lawyer to revolutionary to prisoner to president was glorious, and also deeply fraught with international pressure about the terms of what a free South Africa would be. Those pressures are still evident in how unequal South Africa remains, despite the fact that it had the most globally significant late-20th-century freedom movement and has arguably the most progressive constitution in the world. At any rate, what I most remember from that day is Mandela noting that this was only the third such event: “George Washington, Winston Churchill, and an African.”

That category of distinction, “an African,” was heavily weighted. An African, in the history of Western global domination, was a being of general dishonor. But not there. And not in these works of art. Though all specific, they also register as generally and collectively Black, a subversion of general dishonor into collective homage.