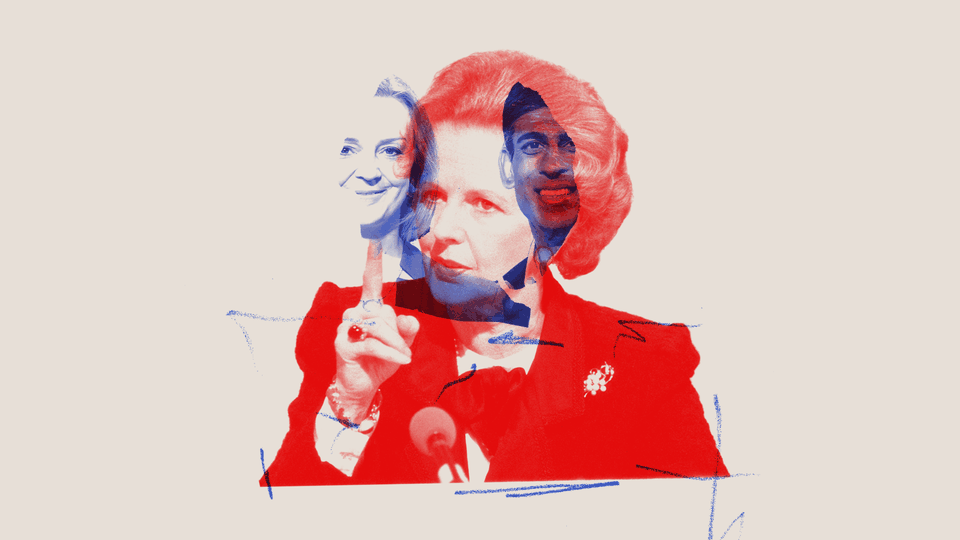

For Britain’s Tories, the Answer Is Always Margaret Thatcher

In their vying claims to Iron Lady nostalgia, the leadership contenders reveal a Tory party struggling for coherence and renewed purpose.

After 12 years in power, Britain’s Conservative Party has hit a wall, unsure of what it is and what it stands for, what its mission is supposed to be, and how it’s supposed to fulfill it. Having replaced David Cameron with Theresa May, then May with Boris Johnson, it is now replacing Johnson with one of two candidates, both of whom are—once again—demanding a new direction for the party and, in turn, the country. Never has Benjamin Disraeli’s angry jibe that “a Conservative Government is an organized hypocrisy” seemed so apt.

During this Conservative era, Britain has become poorer, taxes have gone up, and wages have stagnated. And yet, during this time, the Tory party has been able to successfully reinvent itself thanks to Brexit, winning a once-in-a-generation majority to reform the country in the process.

So we find ourselves with the strange spectacle of Johnson’s two prospective successors—Rishi Sunak, the former chancellor, and Liz Truss, the current foreign secretary—trying to present themselves simultaneously as the candidate of change and of continuity: the defender of Johnson’s great realignment in 2019, when millions of former Labour supporters voted Conservative, and the embodiment of the party’s traditional values that came before.

Both Sunak and Truss are promising to return the party to its core beliefs of low taxes and competence, certainty and seriousness—the party, in other words, of Margaret Thatcher. Both Sunak and Truss have declared themselves Thatcherites. For Sunak, that means adhering to fiscal conservatism to tackle inflation; for Truss, it means cutting taxes to go for growth. Each claims that their Thatcherism is the true Thatcherism—Truss even seems to be dressing up as the party’s great heroine to make the point.

In many ways, the whole spectacle is profoundly absurd. Here we are in 2022, with a host of new problems to address: war in Europe, the ongoing effects of a once-in-a-century pandemic, inflation at a 40-year high, an aging population, Brexit, and a bubbling political crisis in Northern Ireland. Economically, the country is falling behind its peers; politically, it appears chronically unstable; socially, it remains divided over issues of fundamental importance, including its very existence as a single state. Meanwhile, the great institutions of the nation are no longer functioning as they should, buckling under the strain of mismanagement, cuts, short-termism, and scandal.

But while the country is evidently not working, it is not not working in the same way that it wasn’t in 1979. Union power is no more. Unemployment is not a problem. There are few hulking nationalized industries to privatize, few marginal tax rates to slash, and less money to be “handbagged” out of Europe.

Presented with a chance to renew itself in government for the third time in six years, however, the Conservative Party has chosen instead to put on a kind of schoolhouse production of a time gone by, donning the same costumes and deploying the same battle cries, as if to reassure supporters that it still has something to say.

In times of great upheaval, political leaders offer parallels with past glory (or ingloriousness) as reassurance that the nation can once again rise to the challenge. There is a difference, though, between conjuring up the spirits of the past to smuggle a revolution in time-honored disguise, as Karl Marx put it, and simply grasping for the past because you’ve run out of things to say about the present.

In Disraeli’s great novel Coningsby, the 19th-century titan took aim at that awful new invention, “conservatism.” Disraeli was a firebrand radical, fiercely opposed to the first ever “Conservative” prime minister, Robert Peel, who had split the Tory party by supporting free trade over tariffs. Disraeli, in contrast, was in favor of protectionism because it maintained the established order, which he believed served all those in society—the monarch and the multitude. The dispute between Disraeli and Peel continues to play out today—the former the father of moderate “one nation” conservatism, the latter the hero of many modern Brexiteers.

In Coningsby, Disraeli demanded to know what this new Conservative Party wished to conserve beyond whatever resources and policies it had inherited when it took office, given that it did not seem to be concerned with the principles that supported the old order. The Conservative Party, he wrote, was a rudderless body devoid of principle, buffeted by the whims of public opinion.

“Whenever public opinion, which this party never attempts to form, to educate, or to lead, falls into some violent perplexity, passion, or caprice,” he blasted, “this party yields without a struggle to the impulse, and, when the storm has passed, attempts to obstruct and obviate the logical and, ultimately, the inevitable, results of the very measures they have themselves originated, or to which they have consented.”

I find it hard to come up with a better description of what has happened to the Conservative Party over its 12 years in power. It offered a referendum on Britain’s membership to the European Union but did not know how to follow through on the result; it negotiated, signed, and ratified a Brexit divorce deal whose consequences it now disavows; and it won its biggest majority in 30 years on a pledge to rebalance the country’s economy and rip up the old orthodoxy—only to now balk at the costs of doing so.

Disraeli warned that in such a moment, when the party faced the consequences of its own choices, its leaders would be forced to choose between “Political Infidelity and a Destructive Creed.” The strange thing about Truss and Sunak today is that they seem to offer us a perfect combination of the two.

Truss has chosen political infidelity: Once a supporter of the Liberal Democrats and of Britain’s membership in the EU, she is now a hard-line conservative who says she was wrong to have ever backed Remain, pursuing Brexit with the zealous certainty of a convert. Sunak, having found himself badly trailing Truss in the polls, has fallen on the destructive creed, ramping up his rhetoric on core conservative issues such as immigration, China, and economic nationalism in hopes of winning.

Disraeli offers us a handy guide as to why this old party of reaction and conservation is able to somehow be one of the most meritocratic in the Western world.

Despite being an obvious outsider who suffered anti-Semitic abuse throughout his career—he was of Jewish heritage—Disraeli was a Tory who supported what he called England’s “aristocratic principle.” Disraeli wrote that this did not mean rule by an unchanging elite, but an aristocracy that “absorbs all aristocracies, and receives every man in every order and every class who defers to the principle of our society, which is to aspire and to excel.” This, as George Orwell once much more skeptically pointed out, was how England was able to maintain order, creating “an aristocracy constantly recruited from parvenus.” And no party has more parvenus than the Conservatives, from Disraeli himself to Thatcher—the country’s first female prime minister—to John Major, Thatcher’s successor, who was drawn from the working class. That this year’s Conservative Party leadership contest was among the most ethnically diverse of any held in the West is less of a break with the past than it first appears.

Disraeli also offers us a guide to how the Conservative Party has been able to renew itself—but also why it often doesn’t. In 1867, still years away from the premiership, he gave a speech in Edinburgh in which he set out the challenge for a party seeking to conserve the established order in a world that was always changing.

In a progressive country, Disraeli declared, change is constant: “The great question is not whether you should resist change which is inevitable, but whether that change should be carried out in deference to the manners, the customs, the laws, and the traditions of a people, or whether it should be carried out in deference to abstract principles.” This, he said, was the essential divide in politics: “The one is a national system, the other […] a philosophic system.” In this divide, he argued, the Tory Party was the national party; its opponents were the philosophers in favor of abstract creeds.

The problem the Tories now face is that they are stuck in a rut trying to be both. Brexit, in its most essential sense, is an expression of a nation, a cry against the change happening within the EU undermining the traditions of a people. It is a conservative revolution to protect and preserve, not an expression of a universal ideal. Yet both Sunak and Truss are competing to show how much they believe in the creed of Brexitism and its forerunner, Thatcherism.

Both candidates, in fact, are really liberals, not Tories—Truss ideologically, Sunak pragmatically. Truss is a believer in liberty, markets, global free trade, and capital. In recent years, these have been confused with conservative values, but they are certainly not Tory in the Disraelian understanding. For Sunak, the challenge is that underneath his belief in sensible, sound management, there are no real beliefs at all, other than those Disraeli so loathed as conservative. This is the issue that dogs Sunak, the source of leaks from the cabinet about his skepticism over spending billions to support Ukraine and his willingness to cut a deal over Northern Ireland. These policies might seem pragmatic, but are they rooted in principle?

The candidates and the party are no longer focused on the true vocation of the Tory: the careful stewardship of the nation and its institutions, upon which the Tory believes rest the country’s wealth and freedom. Instead, what they offer is a drive for ideological purity as the institutions of the state wither.

“Whenever the Tory party degenerates into an oligarchy it becomes unpopular,” Disraeli wrote caustically. “Whenever the national institutions do not fulfil their original intention, the Tory party becomes odious.”

This is the situation the party now finds itself in.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.