Dobbs Is No Brown v. Board of Education

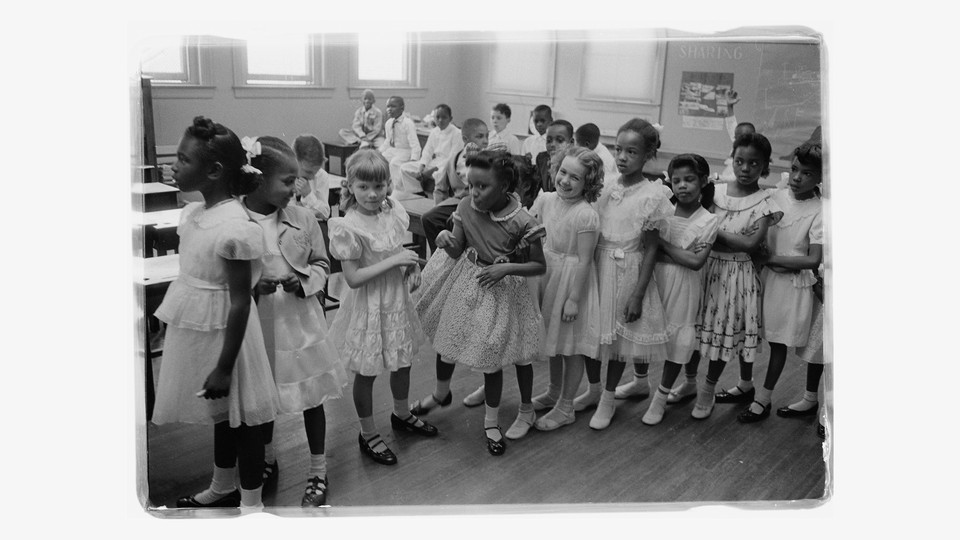

Conservatives think they are righting a historical wrong, but the two decisions represent entirely different approaches to the law.

Homer Plessy is being recognized more and more. In 1896, the light-skinned, French-speaking Louisianan gen de couleur was memorialized in what is considered one of the worst Supreme Court decisions in American history, Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld Jim Crow segregation laws. The decision is second in infamy only to the Dred Scott decision, which upheld slavery and declared that Black men had no rights that white men were bound to respect.

As one of the worst Supreme Court precedents, Plessy is frequently invoked whenever someone wants to make a case for overturning some other opinion they disagree with. Justifying his decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, the 1973 case that established a constitutional right to end a pregnancy, Justice Samuel Alito repeatedly raised Plessy in his opinion.

“A precedent of this Court is subject to the usual principles of stare decisis under which adherence to precedent is the norm but not an inexorable command,” Alito wrote in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. “If the rule were otherwise, erroneous decisions like Plessy and Lochner would still be the law.” When former President Barack Obama criticized the decision on Twitter for having “reversed nearly 50 years of precedent,” Republican Senator John Cornyn of Texas responded, “Now do Plessy vs Ferguson/Brown vs Board of Education.”

Cornyn was not, as some liberal critics suggested, calling for Brown to be overturned. Like Alito, he was invoking the Brown decision as a correct decision overturning an incorrect precedent, which was Plessy. Allowing states to ban abortion, in this analogy, is like declaring Jim Crow segregation unconstitutional. The analogy is a flawed one, however, because the reasoning in Dobbs echoes the legal logic of Plessy far more than that of Brown. Alito has described his own legal philosophy, originalism, as “the idea that the Constitution has a fixed meaning; it doesn’t change. It means what people would have understood it to mean at the time it was written.” Specifically citing the Obergefell decision legalizing same-sex marriage, Alito complained that “whatever liberty means, though, in 1868 it did not mean the right to enter into a same-sex marriage.” Yet by that reasoning, the Plessy decision was not “egregiously wrong.” Alito’s stated legal philosophy would never have found Jim Crow segregation unconstitutional, but that doesn't stop conservatives now from citing Plessy to justify overturning Roe.

Plessy was chosen as a plaintiff in part because of his racial ambiguity. Louisiana was unique among the former Confederate states in having antebellum Black upper and middle classes, many of whose members were the manumitted descendants of slaveowners. After the war, the interests of those classes were aligned with the newly emancipated in seeking equal rights for all regardless of race. But the very existence of that community also highlighted the arbitrary nature of segregation. “In fact,” the historian John W. Blassingame wrote in Black New Orleans 1860–1880, the population of the city “was so mixed that it was virtually impossible in many cases to assign individuals to either group.”

Now accountable to Black men at the ballot box, Reconstruction legislators passed state laws requiring that businesses of public accommodation serve all without discrimination on the basis of race. Those laws were repealed or struck down after Reconstruction, but even before the Fourteenth Amendment, Black leaders and newspapers in New Orleans advocated for such measures because they believed that “the best way to end the custom of segregation and the whites’ habit of looking down on blacks was to have equality before the law,” Blassingame wrote.

In Separate, a history of Plessy, the journalist Steve Luxenberg writes, “The newspapers weren’t publishing photographs routinely, but they were offering facial sketches of people in the news, a popular innovation. None appeared of this presumptuous ‘Negro Traveler’ who dared to ride with whites.” Before boarding the segregated train car, Plessy was reportedly asked by the conductor whether he was “white” or “colored.”

Plessy’s supporters hoped that his racial ambiguity would illustrate the absurdity of Jim Crow laws and racial classifications to the justices. No place in America illustrated the absurdity of “separation” based on race like New Orleans. Indeed, the law made an exception, allowing “nurses” into white cars—Black people threatened white purity, but not so much that wealthy whites were willing to give up their child care. But the justices may not have appreciated being confronted so directly with that hypocrisy.

Either way, their strategy failed. “As a conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment is concerned, the case reduces itself to the question whether the statute of Louisiana is a reasonable regulation, and with respect to this there must necessarily be a large discretion on the part of the legislature,” Justice Henry Billings Brown wrote in his infamous opinion upholding post-Reconstruction Louisiana’s segregation law. “In determining the question of reasonableness, it is at liberty to act with reference to the established usages, customs, and traditions of the people, and with a view to the promotion of their comfort, and the preservation of the public peace and good order.”

The Fourteenth Amendment, Brown wrote, “could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.”

Justice John Marshall Harlan, in his historic dissent, wrote, “I am of the opinion that the state of Louisiana is inconsistent with the personal liberty of citizens, white and black, in that state, and hostile to both the spirit and letter of the constitution of the United States. If laws of like character should be enacted in the several states of the Union, the effect would be in the highest degree mischievous.” Harlan’s divergence from the majority was not just a matter of constitutional interpretation but life experience. As Luxenberg writes, initially a conservative, pro-slavery unionist, Harlan had spent time prosecuting the Klan in Kentucky and had befriended the abolitionist Frederick Douglass. These experiences altered his understanding of what equal protection under law meant.

Harlan’s dissent was prophetic. Black American civic and political rights had already been severely constricted since the end of Reconstruction; the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence would ensure that the Constitution posed no threat to the emerging system of racial apartheid.

But who was right about what the Constitution said? As the historian Eric Foner writes in The Second Founding, during the debate over the Fourteenth Amendment, “Democrats claimed that the bill’s ‘logical conclusion’ was black suffrage, integrated public schools, interracial marriage, and complete ‘political’ and ‘social’ equality—a charge Republicans vociferously denied.” Foner continues, “Opponents also contended that the bill would bring about a revolutionary change in the federal system, transforming a ‘free republican form of government into an absolute despotism.’ Republicans insisted that the measure contained ‘no invasion of the legitimate rights of the states.’”

Plessy himself showed that “separation” was already something of a fiction. But white Americans were scandalized enough by the idea of integration that Republicans, the vanguard of racial justice at the time, insisted that integration and equal rights were not synonymous. Yet Harlan’s dissent was correct that the equality envisioned by the Fourteenth Amendment was an impossibility under that understanding of the Constitution, and that the rights of Black Americans under that interpretation would be forfeit.

By the time Brown reached the Supreme Court decades later, Chief Justice Earl Warren acknowledged that “the debates on the readmission of the Southern states into the Union fail to disclose any definite understanding as to the effect of the Fourteenth Amendment on school segregation.”

Nevertheless, Warren famously concluded that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” But he did so in part by reasoning that “we cannot turn the clock back to 1868 when the Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson was written.” Brown is not, to put it plainly, an originalist ruling. Its singular importance in American history and culture has resulted in some half-hearted originalist attempts to claim it. But as Harry Litman has written, the simple fact is that “the Fourteenth Amendment requires equal protection of the laws. For legislators—and citizens and judges—in 1865, that principle didn’t mandate integrated schools; for Americans in 1965, it did.”

Alito’s opinion in Dobbs valorizes Brown while sneering at its underlying philosophy. In responding to the dissent noting Brown’s acknowledgment of societal changes, Alito gasps, “Does the dissent really maintain that overruling Plessy was not justified until the country had experienced more than a half-century of state-sanctioned segregation and generations of Black school children had suffered all its effects?”

Alito finds accusations of racism deeply offensive and uncivil, unless he is making them. But as the dissent countered, “if the Brown Court had used the majority’s method of constitutional construction, it might not ever have overruled Plessy, whether 5 or 50 or 500 years later.” Five hundred years is perhaps overly generous. Alito’s disgust with Plessy is him substituting his own political sensibilities for his professed legal philosophy—something he and the other justices already do regularly despite their proclamations to the contrary.

Looking back from 2022, Homer Plessy’s understanding of the Fourteenth Amendment was obviously the correct one. But it was not what most people—which almost inevitably means most white people—then “understood it to mean,” Alito’s lodestar for constitutional interpretation. Reacting to the 1883 decisions eviscerating the 1875 Civil Rights Act, in many ways the 19th-century forerunner to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Frederick Douglass lamented that the Supreme Court had “construed the Constitution in defiant disregard of what was the object and intention of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment,” interpreting “both the Constitution and the law with a strict regard to their letter, but without any generous recognition of their broad and liberal spirit.” Familiar.

The most compelling argument that originalism is compatible with the Brown decision was made in 1995 by the conservative legal scholar and former judge Michael McConnell, who largely relies on the debate over the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which took place after the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified. McConnell writes that for the era’s Republicans, the issue “was not relations between the races but realization of an ideal of a government of citizens who were equal in their rights before the law, however unequal they might be in other respects.”

The fact that the strongest “originalist” case for Brown relies on a legislative debate that occurred after the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted is ironic, because to accept it means accepting that the amendment’s framers understood the concept of equal protection as an evolving one, not meant to remain frozen in a time when integrated schools and interracial marriage were deeply unpopular among white men, who were then the overwhelming majority of both voters and legislators. Those framers later came to understand what Plessy and Douglass understood from the start: that, as the attorneys in Obergefell argued, “the abiding purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment is to preclude relegating classes of persons to second tier status,” and that this purpose demands an examination of society’s present and not just its past.

What this means is that the majority that signed on to the opinion in Dobbs could not have reached the Brown verdict by Alito’s own acknowledged method of constitutional interpretation, his jab at the dissenters notwithstanding. Assuming that he would have understood the Constitution as Plessy and Douglass did is the judicial version of insisting that you would have joined John Brown or fought in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. (Justice Antonin Scalia actually did this, publicly proclaiming in 2009 that he would have dissented with Harlan.) As the law professor Ronald Turner notes, for all his prophetic foresight about Jim Crow, Harlan did not believe that the Constitution he described as “colorblind” outlawed segregated schools: He upheld them a few years after his dissent in Plessy, thus contributing to the apartheid regime he warned would come to pass.

Dobbs is no where near as essentialist about gender as Plessy is about race. Yet despite Alito’s disgust for Plessy, his own opinion in Dobbs recalls the legal logic of his disavowed predecessors. Echoing Justice Brown’s insistence that in evaluating Jim Crow laws, “there must necessarily be a large discretion on the part of the legislature,” Alito writes that “respect for a legislature’s judgment applies even when the laws at issue concern matters of great social significance and moral substance.” Alito’s insistence that the Constitution only “protects un-enumerated rights that are deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition” recalls Justice Brown’s conclusion that “in determining the question of reasonableness, [the state legislature] is at liberty to act with reference to the established usages, customs, and traditions of the people.”

Even in 1954, this logic would have meant upholding Plessy. And segregationists said as much in their Southern Manifesto, insisting that “the debates preceding the submission of the 14th amendment clearly show that there was no intent that it should affect the systems of education maintained by the States,” and that “every one of the 26 States that had any substantial racial differences among its people either approved the operation of segregated schools already in existence or subsequently established such schools by action of the same lawmaking body which considered the 14th amendment.”

Interracial marriage and integrated schools and businesses of public accommodation were not “deeply rooted” in American history and tradition, nor are they explicitly mentioned in the Fourteenth Amendment. Indeed, the amendment itself was meant to end the deeply rooted tradition of denying civic and political rights to American citizens, and help create a new birth of freedom in which the promises of liberty were not confined to a chosen few.

Simply put, the Supreme Court is a site of political combat whose significant decisions are only superficially moored to legal philosophy. The Brown ruling happened because there were enough justices willing to strike down Plessy, and the Dobbs ruling happened because there were enough anti-abortion-rights justices to strike down Roe. The notorious precedent that the Dobbs majority cites to justify overturning Roe is one it would never have overturned through strict adherence to its own principles. Dobbs is a victory conservatives won at the ballot box by exploiting the countermajoritarian levers of American democracy, and it can be reversed only by similarly political means.

Black newspapers at the time understood the Plessy verdict as catastrophic, but their counterparts in the mainstream white press covered it as a minor decision. Both before and after Roe, GOP apparatchiks sought to downplay the significance of the ruling, in order to minimize the potential political fallout for the party. But the tidings of the world Dobbs will create are grim.

Allowing states to criminalize abortion promises a regime of state violence, surveillance, and prohibition unlike anything Americans have seen before, one that roughly half of the population will not be subject to, because they cannot get pregnant. Conservatives are mobilizing to criminalize speech about abortion, including making it a crime to “pass along information ‘by telephone, the internet or any other medium of communication’ that was used to terminate a pregnancy.” In defiance of Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s whimpering concurrence insisting on a constitutional right to interstate travel, some Republican-controlled states are considering banning travel across state lines to get an abortion and prosecuting those who do. To enforce bans on abortion, GOP-run states intend to make use of “not just call histories, text messages and emails that may be used to prosecute, but also location data, online payment records, Google searches and fertility tracking apps.” Such information may also be of use to the anti-abortion bounty hunters states like Texas have deputized to invade their fellow citizens’ private lives, and then snitch on them for a cash reward.

“Fetal-personhood laws have passed in Georgia and Alabama, and they are no longer likely to be found unconstitutional. Such laws justify a full-scale criminalization of pregnancy, whereby women can be arrested, detained, and otherwise placed under state intervention for taking actions perceived to be potentially harmful to a fetus,” Jia Tolentino writes in The New Yorker.

In Texas, already, children aged nine, ten, and eleven, who don’t yet understand what sex and abuse are, face forced pregnancy and childbirth after being raped. Women sitting in emergency rooms in the midst of miscarriages are being denied treatment for sepsis because their fetuses’ hearts haven’t yet stopped. People you’ll never hear of will spend the rest of their lives trying and failing, agonizingly, in this punitive country, to provide stability for a first or fifth child they knew they weren’t equipped to care for.

Beyond laws targeting women, conservative attorneys have already begun to apply Alito’s maxim about respecting only those rights “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition” to attack other groups that the conservative movement sees as profitable scapegoats. The conservative activist who devised Texas’s abortion-bounty law has publicly proclaimed his intention “to systematically dismantle decades of rulings he believes depart from the language of the U.S. Constitution or that impose constitutional rights with no textual basis,” which include “court-invented rights to homosexual behavior and same-sex marriage.” Alito’s half-hearted disclaimer that Dobbs applies only to abortion rights has not prevented conservative activists from seeing his words as an invitation, and those words will not restrain him or the other justices should they choose to ignore them when the time comes.

We cannot know how far this emerging legal regime will go. It need not be morally comparable to what followed Plessy in order to subject half of the population to a separate and unjust legal regime on the basis of immutable characteristics. In attacking basic rights of freedom of speech, conscience, association, and movement, the Republican agenda for the post-Roe era already bears a greater resemblance to the “mischief” Harlan warned about being directed at the basic rights of a class of people in the name of “tradition” than they do to the freedom and equality promised by the Fourteenth Amendment.

In Dobbs, Alito and his defenders want to believe he was writing this generation’s Brown. But the decision whose logic it mirrors is Plessy.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.