Whatever This Is, It Won’t Be Build Back Better

At this point, the ideal climate bill is out of the picture. Here are two ways to make sense of Democrats’ next move.

Welcome, all. We are gathered here today to mourn Build Back Better, President Joe Biden’s overstuffed and too ambitious domestic-policy package.

It had its flaws, of course. We all do. But I am not here to dwell upon any of those. I wish, instead, to speak only of BBB’s climate provisions, because, had the bill passed, it would have been the most aggressive action against climate change we have ever seen from Congress.

Build Back Better would have prevented more than 5 billion tons of carbon pollution from entering the atmosphere, according to an analysis by a team of researchers led by Jesse Jenkins, a Princeton engineering professor. Those emissions reductions would have made up more than 90 percent of America’s commitment under the Paris Agreement, allowing the country to nearly cut its annual emissions in half, compared with their all-time high, by 2030.

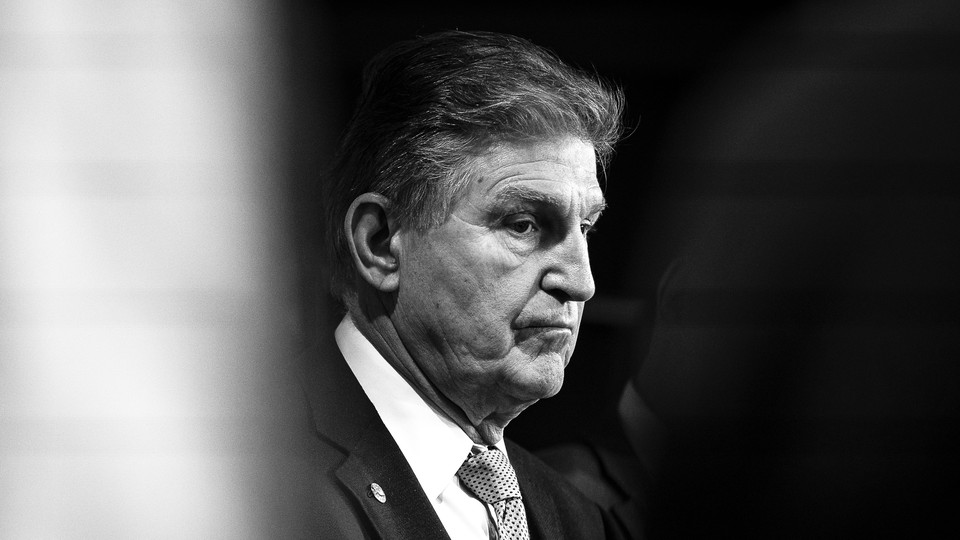

Yet it is no more. Build Back Better perished in December, the victim of a sneak attack by Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia. Congress is not going to pass it. Democrats who spent years salivating over a bill like Build Back Better should forget about it. It will never become law.

I raise this morbid point because at some point in the next week or two, Senate Democrats are probably going to release a new reconciliation bill. This slimmed-down package is still largely a mystery, but it could include up to $300 billion for climate and energy provisions, according to NBC News. The working assumption is that the provisions, which might include clean-energy tax credits or manufacturing support, will resemble moderated—if not Manchin-ified—versions of some key parts of Build Back Better. (There’s a reason that Senator Mitt Romney quipped that this new effort should be called “Build Back Manchin.”)

And when this new package lands, many people will have the immediate urge to compare it to Build Back Better—to search for all the things that Build Back Better once did that this new bill will not. In this light it will be found lacking, almost by definition. After all, BBB devoted more than $550 billion to the climate; this one will be $300 billion, tops. All the negotiations are still under wraps, but Manchin’s influence and his demonstrated willingness to veto bills will very likely warp the final product. Given the senator’s background, his concerns about energy security, and his literal ownership of a coal-trading company, it isn’t inconceivable that the bill could even boost some fossil-fuel supplies.

But at this point, the right comparison for a climate bill is not BBB—it’s nothing. So rather than holding up the bill to a dead policy, we should ask these two questions instead: Will this new bill reduce American emissions compared with doing nothing at all? And will it put the world closer to decarbonizing?

I want to be clear that we don’t know the answer to either question yet. Given the party’s public commitment to climate action, it seems probable that any deal that could earn 50 Democratic votes in the Senate would slash emissions at home and put the world on a right path. But given Manchin’s idiosyncratic influence, that might not be a sure bet.

The first question is mostly numerical. Soon after the proposal is released, energy modelers, including Jenkins and his team, will forecast what it might mean for emissions over the next few decades. Those simulations aren’t perfect—they assume, for instance, that current trends in the global energy system will hold, even though the current system is anything but stable—but they should help clarify the scale of change that the policy will accomplish. Those simulations can then be put to the test, subjected to a kind of mental war-gaming by experts: What will happen to emissions if oil gets really cheap again? What will happen if lithium, copper, and other minerals needed for green-energy technology become hard to find on global markets?

The second question—what a climate bill, even a slimmed-down one, might mean for global decarbonization—is far harder and more subjective. Answering it requires having a mental model of how the energy transition might play out around the world and running through multiple simultaneous guesses about war, peace, and prosperity. Remember that decarbonizing isn’t simply a matter of reducing fossil-fuel emissions; it requires building an entirely new zero-carbon energy system in its place. And there is no guidebook, no clear precedent, about how to do that. If you believe, for instance, that replacing the energy system requires abolishing capitalism or restricting the power of the American state, then you’ll be unlikely to fall in love with whatever Democrats come up with.

But if you tend to think the transition will be more piecemeal—with American consumers switching to low-carbon alternatives when they are cheaper, better, or more easily available, and thus helping lower costs of those technologies for the rest of the world—then the deal might be a bit more palatable. If you’re worried about a broader U.S.-China conflict in the next few years, then you’ll reach a third conclusion. The key is holding multiple possible futures in your head and seeing how the policy will hold up in all of them.

In the end, answering the global question will require making an educated bet. Sometimes, how people view trade-offs change over time. In 2015, the Obama administration struck a deal with congressional Republicans to lift a 40-year-old crude-oil export ban in exchange for a multiyear extension of solar and wind-energy subsidies. Now some on the left wonder whether the deal was worth it. What would make me confident about such a bet? I’d want to see whether a deal helps boost not only demand for clean-energy technologies (say by subsidizing new electric-vehicle purchases) but also their supply. I would love to see policies that help make abundant the raw materials, industrial tools, and on-the-ground expertise needed for the energy transition.

But the question of what would be best for global decarbonization isn’t strictly a question of tons. Climate action proceeds by momentum, with small wins abetting big wins, in a process that I’ve called the green vortex. And the world could use a climate win right now, especially from America. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting energy crisis has forced the European Union into backtracking on some of its promises. Germany, which is shutting down its zero-carbon nuclear plants, has been forced to reactivate coal-fired power plants. This will boost carbon emissions and may endanger its Paris Agreement commitments. This isn’t to say that the EU lacks real climate wins, but that the Ukraine war has thrown the continent’s plans into disarray.

We will know more, of course, when—and if—Democrats unveil their proposal. But no matter what, this is likely the party’s last chance to make legislative climate policy with enough time to hit America’s Paris Agreement targets—and, with it, avert the most damaging effects of global warming. Even with federal assistance, it takes time to set up zero-carbon energy infrastructure—time to rustle up the tens of billions of dollars to grow green companies, to finance construction, to transport raw materials and assemble them in the right spot. Reaching net-zero carbon emissions, which the U.S. hopes to accomplish by 2050, requires multiple decade-long build-up cycles, so getting as much policy on the books as possible, as early as possible, is crucial.

But even that doesn’t capture the stakes of this moment. The Republican Party on the whole still does not take climate change very seriously, and not only are Democrats headed toward likely ruinous midterm elections come November, but the country’s political demographics mean that the party faces long odds over the next few years. As I’ve previously written, Democrats can win 51 percent of the vote in the 2022 and 2024 elections and still lose eight Senate seats.

That all means that this really is Democrats’ last chance. They better deliver.