Lapvona

By Ottessa Moshfegh

Ottessa Moshfegh’s latest novel takes place in Lapvona, a medieval fiefdom ruled over by a vain and gluttonous lord, Villiam. The story begins with Marek, a masochistic, God-fearing 13-year-old boy who craves pain and punishment because he knows that God loves those who suffer. His father, Jude, cares far more about the lambs he keeps than about his son. The village they live in is full of odd people and cruel tragedy—an old woman who survives a plague as a child and spontaneously starts lactating in her 40s becomes a wet nurse for most of the village’s children; a brutal summer drought overtakes the village while Villiam lavishes by his manor’s reservoir. Lapvona flips all the conventions of familial and parental relations, putting hatred where love should be or a negotiation where grief should be. It is ultimately the story of a boy whose parents really don’t care for him, and the corruption and tragedy that he falls into because of it. Through a mix of witchery, deception, murder, abuse, grand delusion, ludicrous conversations, and cringeworthy moments of bodily disgust, Moshfegh creates a world that you definitely don’t want to live in, but from which you can’t look away. — Maya Chung

The Latecomer

By Jean Hanff Korelitz

From birth, the Oppenheimer triplets, Harrison, Sally, and Lewyn, operate with an unspoken pact of mutual avoidance. They have it all: a stately house, wealth, nearby grandparents, and a mother, Johanna, who brings and keeps her family together through sheer will. But she can’t stop her husband, Salo, from straying, and she can’t bring her children closer to her or to one another. In adolescence, they act like magnets with the same charge; for example, Sally and Lewyn both attend Cornell, where they claim to everyone that they don’t know each other (which eventually causes them both deep harm). By adulthood, their shared dislike crystallizes into open disdain and anger. But, as the title suggests, they’re not the only Oppenheimers with a stake in the family’s affairs. Though their domestic drama gets more tangled with each passing year’s refusal to address it, someone eventually arrives with the intention of cutting through the knot. Read it now to get ahead of the forthcoming, inevitably star-powered TV version—the last Jean Hanff Korelitz adaptation, The Undoing, had Nicole Kidman as the lead, and Mahershala Ali is attached to an upcoming series based on Korelitz’s The Plot. — Emma Sarappo

You Made a Fool of Death With Your Beauty

By Akwaeke Emezi

Akwaeke Emezi is well versed in writing the tender devastation of flesh. Their critically acclaimed debut novel, Freshwater, features a slinky, wounded narrator—a deity’s child, who speaks from the first-person plural—fighting and grieving the restrictions of living in a human body. Their memoir, Dear Senthuran, looked squarely at the author’s own struggles with embodiment. Emezi’s latest offering, You Made a Fool of Death With Your Beauty, is in many ways a classic romance novel; it may at first glance seem like a radical departure for a writer who typically deals in spirituality and mortality. But here, too, Emezi makes mourning their centerpiece, even as sex and seduction form the base of the book. A young widow and an artist named Feyi is tentatively coming to terms with living after losing her lover. Between breathlessly erotic encounters and lavish, tropical escapades, Feyi returns again and again to that stark pain. The novel is somehow a beach read and a psychological portrait, and is likely to spark conversations both sultry and vulnerable. — Nicole Acheampong

Happy-Go-Lucky

By David Sedaris

David Sedaris is back, doing the thing his readers have come to adore: offering up wry, moving, punchy stories about his oddball family. This batch also touches on some of the more tumultuous moments of our past two years, sometimes pretty irreverently. Reading Sedaris on, say, his pathetic efforts to stockpile food in the early days of the pandemic is sublimely funny—he ends up with an assortment that includes a pint of buttermilk, taco shells, and a pack of hot dogs. These essays also have more darkness and death than his earlier work, building off themes he began exploring in his previous collection, Calypso. The pieces range widely, following the path of Sedaris’s travels and his eccentric mind, but a through line involves his nonagenarian father, who is living in an assisted-care facility and whose eventual death is captured in these pages. This is one of the more complicated relationships of Sedaris’s life, and he is unflinching as he tries to understand who his enigmatic father was, and how living with him altered the shape of his own existence. — Gal Beckerman

Summer Reading Guide

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

If You Want to Read What Your Friends Are Reading

If You Want to Better Understand Our World

The Powerful and the Damned: Private Diaries in Turbulent Times

By Lionel Barber

As someone who has always softly identified with the idea of impostor syndrome without ever having had the energy to lean into anything, I found The Powerful and the Damned captivating for its window into completely alien territory: the ferociously ambitious, hyperconfident male mind. The book is Lionel Barber’s account of serving as editor of the Financial Times from 2005 to 2020—a period during which, we should acknowledge, a thing or two happened geopolitically. His recounting of his front-row seat to the global economy imploding and liberal democracies toppling like sandcastles is almost comically inter–British Establishment: Barber bonds with the governor of the Bank of England over cricket, educates Prime Minister “Dave” Cameron on the political talents of a rising star named Barack Obama, and complains to Rupert Murdoch about how rarely the BBC books him as a guest. During the same period, he also helps set a business model for the FT that insists consumers subscribe for the reporting and insight the paper provides. If Barber’s narrative of tumultuous times is often more gossipy than revelatory, his insight into how power operates and sustains itself is truly intriguing. — Sophie Gilbert

Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup

By John Carreyrou

Theranos, the blood-testing company that fabricated both medical devices and facts, was originally named Real-Time Cures. A clerical error made in the start-up’s early, hectic days meant that its employees, for a while, received their paychecks from “Real-Time Curses.” Bad Blood, John Carreyrou’s account of Theranos’s precipitous rise and even more precipitous fall, abounds with delicious details like that. The book is a victory lap of sorts for the reporter who first exposed the fakery of one of Silicon Valley’s flashiest unicorns; it is also, however, a rich and nuanced tale of ambition that became greed, confidence that became hubris, and disruption that became fraud. It celebrates the people who, horrified by the lies Theranos told to patients and the public, exposed them—often at great cost. If you’ve watched The Dropout, Hulu’s study of the Theranos founder, Elizabeth Holmes (or if you’ve listened to the podcast that the show is based on, or followed the recent trials of the company’s ex-executives), you will likely be as riveted as I was by Carreyrou’s book. Bad Blood understands how easy it can be, in an age of effortless myths, for cures to become curses. — Megan Garber

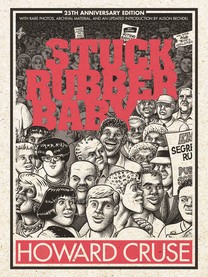

Stuck Rubber Baby

By Howard Cruse

In one memorable panel in Stuck Rubber Baby, hundreds of mourners, assembled for the funeral of Black choir kids murdered by a racist’s bomb in ’60s Alabama, spill across nearly an entire page. “The back of each infinitesimal head is never a mere oval, but always a particular person’s,” the graphic novelist Alison Bechdel points out with wonder in her introduction to the 25th-anniversary edition. That attention to image and story is present in every panel of Howard Cruse’s graphic novel, a fictionalized account of growing up as a white gay man, coming out, and joining the civil-rights movement in the segregated South. His protagonist, Toland, is aware that he’s not much of a hero. He recounts his youth without sanding off his own cowardice or the hurt that he caused others; he’s similarly frank about the racist terrorism and homophobic violence that dominate his hometown. The deeply felt, masterfully rendered comic captures a small but rich slice of how race, gender, and sexuality were experienced and linked in the Jim Crow South—a history whose relevance practically screams from the pages decades later. — E.S.

If You Want to Be Transported to Another Place

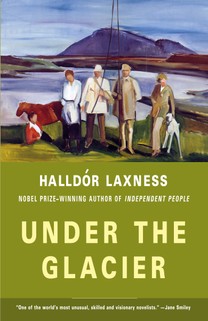

Under the Glacier

By Halldór Laxness

There are rumors circulating about Snæfells Glacier: that dead bodies are left unburied; that the pastor there spends his time shoeing horses instead of preaching; that his wife is gone, and he might be living with another woman. Naturally, the bishop of Iceland sends an emissary to investigate these goings-on. Part comedy of manners, part philosophical inquiry, Halldór Laxness’s audacious novel, translated by Magnus Magnusson, blends soulful ideas with hilarious details. The emissary is just as likely to be musing on the creation of the Earth as he is to be looking for something to eat besides the elaborate cakes his housekeeper keeps making him. As the plot gets stranger—characters, possibly real or merely dreams, proliferate—the glacier only stands out more starkly, and the setting comes to life with a clarifying beauty. (The cries of the nearby kittiwake colony, the emissary notes, sound like “ecstasy on the cliff.”) The question of what exactly is thrumming in the air, water, and soil at and around Snæfells remains mysterious; what’s clear is the cold, vital force at its center. The church might be closed, but, as the pastor puts it, “the glacier stands open.” — Jane Yong Kim

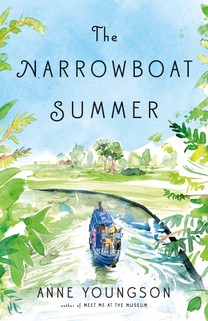

The Narrowboat Summer

By Anne Youngson

As the pandemic continued into its second year, I began planning more road trips, and as a result, began picking up more road-trip novels. This one caught my eye for its unusual choice of starring vehicle: a narrowboat, a type of vessel made to fit British canals. Anne Youngson’s slow-paced but quick-witted tale, following two women who agree to ferry an elderly stranger’s beloved narrowboat up the waterways and back, is undeniably charming, even though it’s heavy on the technical details (canal life involves so many locks and knots!). Sally and Eve, the protagonists, don’t know each other, but they’ve both ended up in a midlife crisis: Sally’s divorcing her husband, and Eve just lost the job that defined her life for 30 years. As predictable as the story may be—every thought-provoking road trip worth reading about involves encounters with kooky interlopers, unexpected speed bumps, and moments of self-discovery, after all—Youngson’s gentle tone, prose packed with British witticisms, and terrifically realized characters delighted me. I finished the novel quickly, feeling like I’d just spent an afternoon drifting alongside Sally and Eve. And then I immediately opened Google Maps and tried to search for street views of their every stop. — Shirley Li

The Perishing

By Natashia Deón

The Perishing is an odyssey through time, Los Angeles, and circuitous, lyrical storytelling. We first meet our narrator as Sarah Shipley, a Black woman on trial in the year 2102. Soon, she is Lou, a teen with no memory who awakens, naked and initially nameless, in an alleyway in 1930. Sometimes he is a man, but always, they are a Black person, and an immortal one at that. In Natashia Deón’s historical-science-fiction tale, reincarnation is a whimsical Trojan horse, inside of which we see how Black people inherit their histories. Deón offers close-up peeks at the City of Angels’s past life—Prohibition, early school integration, the St. Francis Dam collapse—while also imagining its future legacy. The writing is often spiky poetry; Deón’s descriptions of Lou’s surroundings, mirroring her amnesia, are filled with new wonder at an old world, destabilizing objects as ordinary as a pack of gum. “Most people won’t survive everyone who loves them,” the protagonist says, in the voice of Sarah. “Our lives are meant to mimic a passing breeze that won’t return.” Yet in this myth-laden, cross-generational pilgrimage, Black lives move less like wind and more like water: shifting shape but retaining their essence as they cycle through and bear witness to an American city. — N.A.

If You Want a New Take on a Familiar Story

Deacon King Kong

By James McBride

James McBride clearly had the time of his life writing this novel, which is so propulsive and fun that it’s almost hot to the touch. The plot, to the extent that there is one, takes place in late-1960s Brooklyn and involves Deacon Cuffy Lambkin, a.k.a. Sportcoat, an old-timer at the Causeway Housing Projects and an aficionado of the local hooch (called “King Kong”); seemingly out of nowhere, he shoots a local drug dealer, taking off his ear. The mystery of why Sportcoat (a “wiry, laughing brown-skinned man who had coughed, wheezed, hacked, guffawed, and drank his way through the Cause Houses for a good part of his 71 years,” McBride writes) pulled the trigger moves the reader forward, but the book is so much more than that. McBride creates a chaotic and colorful world of characters: There are Italian mobsters and an Irish policeman who falls in love with a virtuous church lady. There’s hidden treasure. There’s the ghostly presence of Sportcoat’s dead wife, who drowned in the harbor but still has plenty to say to her boozehound husband. There’s so much bubbling energy in this imagined New York that it’s impossible to turn away. — G.B.

Dead Collections

By Isaac Fellman

Sol Katz is a 41-year-old trans archivist in San Francisco. Before that, he was a teenager writing fan fiction and arguing in early-internet forums about his favorite ’90s TV show, Feet of Clay (presented as something like a hybrid of The X-Files and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine). Back then, he was also alive. Sol has a disease, vampirism, which, in addition to the obvious effects (he needs transfusions of blood; the sun will kill him), has basically arrested his physical transition—he’d only just started testosterone before joining the undead. When Elsie, the widow of Feet of Clay’s creator, comes to his archive to donate her wife’s papers, the novel becomes a classic supernatural romance: vampire and human fall for each other, hard, and the pair must work out how to be together given their unique circumstances. But it doesn’t dwell on those details. Instead, Dead Collections is a wild trip that follows the metamorphoses both characters undergo after they reveal themselves to each other, demonstrating how a relationship can evolve. It’s wildly funny, sexy, and compelling: I couldn’t put it down. — E.S.

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead

By Olga Tokarczuk

I was initially drawn to Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead because of its mouthful of a title (taken from William Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell”), which almost sounds like a song lyric, if a morbid one. First published in Polish in 2009 and translated in 2018 by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Drive Your Plow is narrated by Janina Duszejko, an elderly woman who lives by Poland’s border with the Czech Republic, as one man after another is murdered in her town. Between translating Blake with her friend and working as a winter caretaker for the summer houses in her remote town, Duszejko investigates the mysterious murders, becoming more and more convinced that the town’s wild animals have committed them as an act of furious revenge against the men who hunt them. Though you can’t help feeling a bit of secondhand embarrassment for her—it’s clear that most of her neighbors see her as a bit of a crackpot, and the police dismiss her outright—her belief is powerful enough that becoming committed to Duszejko’s worldview is easy. — M.C.

If You Want to Feel Wonder About the Universe

When We Cease to Understand the World

By Benjamín Labatut

In Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World, the rapture of scientific genius butts against the horror of war, fascism, and disease. Through five linked sections, the book tells the stories of some of the 20th century’s most important men of science and their pursuit of knowledge. One is Fritz Haber, who saved countless people from starvation by figuring out how to extract nitrogen out of the air, making plant fertilizer abundant, but who also played an instrumental role in the German army’s chemical-warfare program. Another is Karl Schwarzschild, who was the first to find an exact solution to Einstein’s equations of general relativity, introducing the terrifying concept of the black hole. Labatut’s work is a hybrid of fact and fiction, and though those who aren’t well versed in the figures’ biographies and their historical contexts may not realize what’s true and what’s not, I found it almost didn’t matter. I compulsively look up facts while reading, but here, I was content to engross myself in these stories of mad geniuses. Labatut, via a translation by Adrian Nathan West, captures the breathless excitement of discovery so well that I yearned for that sort of heightened experience; then he juxtaposes it against some of the destruction and insanity the work inspired, making me second-guess that desire. — M.C.

Where the Wild Ladies Are

By Aoko Matsuda

Aoko Matsuda’s softly electrifying story collection is full of ghosts, but reading it, I sometimes forgot that fact. In her tales, translated by Polly Barton, spirits coexist with the living, and we don’t always know who’s dead and who isn’t, an authorial choice that subtly emphasizes the humanity of the haunters. Populating these pages are apparitions who wage war, in various ways, on social norms: a nosy aunt, a couple of persistent saleswomen, a mother’s unseen helper. Some of these women seem to take delight in being sweetly annoying; others truth-tell from beyond the grave. “Your hair is the only wild thing you have left,” the aforementioned aunt reminds her niece, scolding her for obsessing over perms and hair removal. The declaration becomes a challenge to the niece, who changes her relationship to her hair—drastically. Matsuda based her vignettes on classic ghost stories, and her characters are ageless, dangerous, and totally untamed. Read this one slowly, to get a tangy whiff of the afterworld as it tangles with daily life. — J.Y.K.

Strangers Drowning: Impossible Idealism, Drastic Choices, and the Urge to Help

By Larissa MacFarquhar

If you happened upon someone drowning in a shallow pond, would you stop to save their life? Your answer, hopefully, is yes. Now what if that stranger was drowning many miles away? What if millions of strangers were drowning—from poverty, disease, war—across the world? Of course, that’s reality, but most of us don’t feel the same urgent responsibility to act on less immediate suffering. Larissa MacFarquhar’s book (whose title refers to a thought experiment raised by the philosopher Peter Singer) profiles individuals who do feel the pain of strangers—acutely, achingly—and dedicate their lives to relieving it. Her subjects include a man who starts a leprosy clinic deep in the jungle; a working-class couple who adopt 20 children; and a pair who survive on a meager budget so that they can donate more than $100,000 each year. But Strangers Drowning isn’t a celebration of these “do-gooders” or a call for readers to emulate them. Instead, MacFarquhar turns the spotlight around, asking why they provoke such discomfort in the rest of us. Years after my first read, I’m still turning over the resulting questions: What exactly do we owe to people we don’t know? And is morality, above all, what makes a good life? — Faith Hill

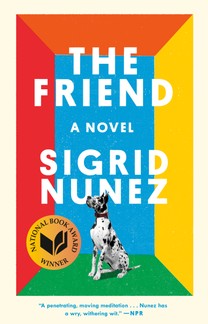

The Friend

By Sigrid Nunez

The central characters in The Friend are, paradoxically, deeply lonely. The nameless narrator has just lost her closest companion to suicide; he was a writer who felt alone in his field, at odds with what he saw as a diminishing appreciation for truth and art. She shared that contention, but now she’s on her own. Then there is his massive, sorrowful Great Dane, who now belongs to her. She doesn’t want the dog at first, but she begins to see that he shares her grief as he lies listlessly facing the wall. To say that this book is about their emerging friendship might make it sound more conventional and cheery than it really is. The actuality is something sadder and stranger, but hopeful still—a meditation on connection, or at least on company. Sigrid Nunez quotes Rainer Maria Rilke describing love as “two solitudes that protect and border and greet each other.” The Friend is a portrait of this kind of bond—one between two individuals, traveling through life essentially solo, who nevertheless recognize each other’s burdens and carry them next to each other. It’s understated, but it’s profound. — F.H.

If You Want a Deep Dive

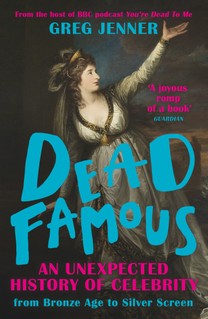

Dead Famous: An Unexpected History of Celebrity From Bronze Age to Silver Screen

By Greg Jenner

Americans tend to talk about celebrities using the language of the cosmos: as stars that orient us as we gaze at them from the ground. Dead Famous is an exuberant exploration of that tendency. Considering celebrity as a force that endures even as it evolves, the historian Greg Jenner offers a host of reminders that TMZ is part of a long tradition. The 18th-century preacher Henry Sacheverell was a firebrand who was also, more simply, a brand. Rapturous audiences fainted at the sight of the 19th-century child star Master Betty. A century later, trying to manufacture his own form of Bettymania, the producer Florenz Ziegfeld spread the story that his partner, the singer Anna Held, bathed in milk in the manner of Cleopatra—and, to put the rumor on the record, enlisted a dairy farmer to sue him for “unpaid bills.” Jenner expands these vignettes, weaving academic theory and rich analysis into his tales of stardom’s past. The result is not a comprehensive history—Dead Famous focuses largely on the U.K. and the U.S.—but a wonderfully illuminating one: a study of what can happen when humans are, as Chaucer put it, “stellified.” — M.G.

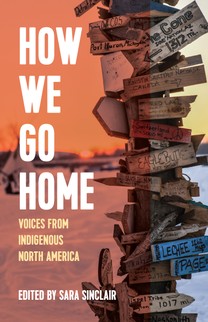

How We Go Home: Voices From Indigenous North America

Edited by Sara Sinclair

At first glance, this collection of 12 oral histories from Indigenous people across North America, supplemented by pages of footnotes offering context, resembles a textbook. But the book’s Cree-Ojibwe editor, Sara Sinclair, uses that scholarly context to demonstrate how injustice and indifference toward Native people for generations led to profoundly similar accounts of tragedy and resilience. Her subjects vary in background, but taken together, they illuminate the shared and acute “soul sickness,” as one put it, of being pushed to reject their identities for the sake of so-called progress at the behest of faceless institutions. For example, the Santa Clara Pueblo activist Marian Naranjo describes how the U.S. government’s installation of the Los Alamos National Laboratory in the 1940s caused damage to sacred sites that she’s still working to reverse. How We Go Home is a rewarding, if tough, read; each narrator details harrowing traumas, and I often needed time to process a finished story before starting the next. But then again, many of the voices made clear that they weren’t sharing their experiences for mere sympathy. “I don’t dwell on how I was harmed,” Geraldine Manson, a Snuneymuxw First Nation elder in residence at Vancouver Island University, told Sinclair, “but I reflect on it.” The collection, compiled for the nonprofit organization Voice of Witness, offers an opportunity to do the same. — S.L.

Black Cool: One Thousand Streams of Blackness

Edited by Rebecca Walker

Rebecca Walker’s slim anthology gives itself a formidable task: pinning down the elusive definitions of “Black Cool,” an aesthetic and a philosophy that echoes across the African diaspora. The essays assembled by Walker feature contributions from a range of artists and thinkers, including bell hooks, Hank Willis Thomas, and Margo Jefferson, and study Black artifacts such as blues music, Air Jordans, and the studio portraits of Malick Sidibé. The book’s tone shifts as fluidly as its focus does, and many of the writers lace their cultural diagnoses with personal anecdotes and vice versa. Originally released in 2012, the 10th-anniversary reissue provides not just scrutiny into the titular phenomenon but also a kind of time capsule from the recent past. A decade out, some of these essays may reflect somewhat dated preoccupations (the recurrent finger-wagging at baggy jeans feels, ironically for this title, downright corny); but other threads, like Dawoud Bey’s ode to swagger or Michaela angela Davis’s fiery defense of Black-style genius, seem timeless. After all, as Davis puts it, “Black cool is an intelligence of the soul”—and soul is forever. — N.A.

Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood

By Mark Harris

The Oscar race for Best Picture in 1968 brought together an unusual collection of films: Bonnie and Clyde, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night, The Graduate, and Doctor Dolittle. Grouped together, these films represented a hinge moment in American film history, from the old to the new, from artifice to authenticity, from hiding from issues like race and sexuality to beginning to confront them head-on. You had both Bonnie and Clyde, one of the most stylistically cutting-edge, provocative, and violent films that Hollywood had ever produced, and Doctor Dolittle, a bloated movie musical and a holdover from the studio system’s heyday. Mark Harris takes that Oscar race as his starting point for a surprisingly rollicking narrative about these five movies. He follows them from inception to reception, and covers the convergence of old stars, such as Rex Harrison and Spencer Tracy, and new ones, such as Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman. The book also speaks to a shift in American culture, the moment when messy narratives of alienation and rage began to make their way into and shatter the illusions of the technicolor world projected on the screen. — G.B.

Illustrations by Robert Beatty