Perfume Genius Sings the Body Electric

The notion of surrender is at the heart of Mike Hadreas’s carnal and sensual new album, Ugly Season.

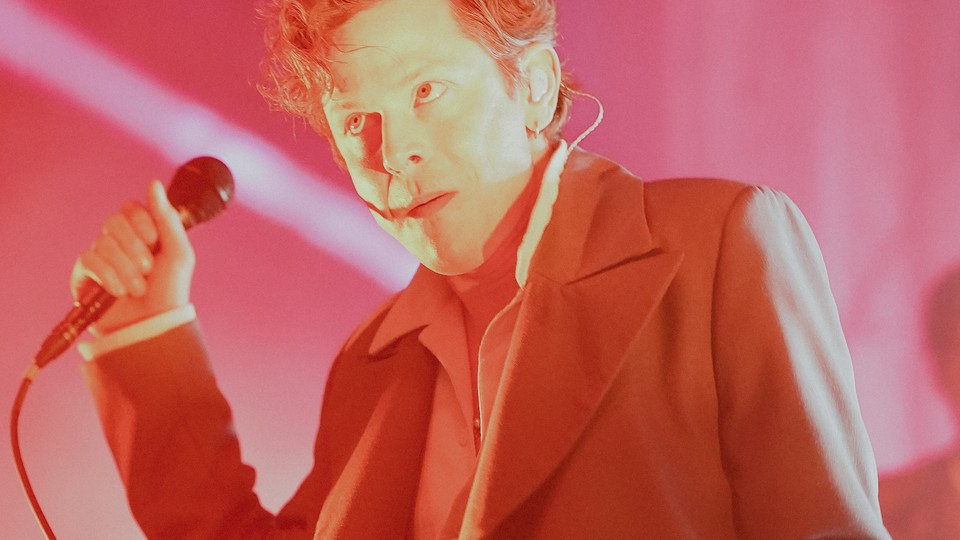

On a warm, late-March night in Washington, D.C., just a few blocks from where Walt Whitman once visited Union soldiers and wooed his beloved Irish horse-car conductor, Mike Hadreas took the mic for a sold-out show. As Perfume Genius, his stage name, he quickly settled into the lilting groove of “Your Body Changes Everything,” from his acclaimed 2020 album, Set My Heart on Fire Immediately. He pitched his voice low and strutted across the stage, charging the room with a current of sexual energy that, to quote a poem by Whitman, “is curiously in the joints of his hips and wrists, / It is in his walk, the carriage of his neck, the flex of his waist and knees.”

Throughout the concert at the historic 9:30 Club, Hadreas shape-shifted, yielding himself to the music’s demands. On “Jason,” a ballad of seduction, he turned vulnerable, whispering the lyrics in a falsetto. Reclining in a chair, he lengthened his lithe frame and opened his legs, an offering to the invisible man standing before him—the one who, in the song, remains clothed while undressing the narrator.

At 40, Hadreas is six albums into a career that has mapped the gay body as a territory of emotional and sensual revelation. His songs have been about finding holiness through passion (“Slip Away”), summoning strength in the face of homophobia (“Just Like Love”), coping with illness and depression (“Describe ”), and reckoning with aging (Set My Heart’s haunting opener, “Whole Life”). In a Zoom interview six weeks after the show, he told me he has found deeper layers in these themes to explore. “For a long time I’ve been obsessed with the idea of transcendence, or, like, leaving the body,” he said. But Hadreas revealed that training to dance—a new artistic endeavor for him—taught him that being more present in the body granted him access to higher spiritual realms in his music. This knowledge is embedded in the bones of his latest album, Ugly Season, which was released today.

Soaked in sweat and decadence, Ugly Season marks a watershed for Perfume Genius, one nearly as momentous for his career as the release of Too Bright in 2014. That record saw him shift from the spare, confessional songs of his first two albums to the lush, sublime, and more rocking realm of chamber-pop. On Ugly Season, Hadreas’s musical references remain diverse; the album pulses with classical flourishes, Middle Eastern tones and instrumentation, West African polyrhythms, pop synthesizers, and his own trademark baroque sensibilities. “More maximal,” he told me. But on some songs, many of pop’s structural conventions are gone. The lyrics are more abstract. Two tracks are completely instrumental, relying instead on a felt narrative humming with chaos and longing. It’s a brave album, sensual and carnal—a sonic feast.

Ugly Season was adapted from a soundtrack to “The Sun Still Burns Here,” an immersive dance performance that paired Hadreas with the choreographer Kate Wallich and her company, The YC. As one of the dancers, Hadreas performed during residencies in Seattle, Minneapolis, New York, and Boston in 2019 and early 2020. Training for the performances, he said, taught him a sweeter, more delicate way to move. “I had to develop a relationship with my body and other people’s bodies in a real way, and not just this sort of improvised, thrashy, bitchy way that I’m used to doing it,” he told me.

With its emphasis on rigor and repetition, the training opened an emotional wellspring for Hadreas. The smallest acts—rolling around, activating his wrists—often caused him to tear up and even weep. Even three years later, it was clear the experience had left a mark. When we spoke, he searched for the right words. “In order for feelings to come up, you have to let them, and I don’t think I let them up very often,” he said. When writing and recording, he could engage with his emotions on his own terms, creating a world in which he retained control and a sense of safety. But dancing was different, he realized: “I didn’t feel like the boss as much anymore. Things were just coming up without me intending or wanting them to.”

This notion of surrender is at the heart of Ugly Season—submitting to a sexual, mystical hunger, and reckoning with the euphoria and disorder that can follow. Hadreas’s faithful listeners will recognize these as familiar themes of his oeuvre. Yet he doubles down on them in this record, embedding them more in the music itself, which broods, crashes, throbs, and caresses while spinning a tale of passion and renewal, a search for enlightenment and divinity through the body—and the bodies of others.

The album opens with “Just a Room,” a dirge that ushers the listener into an aural purgatory. As with other Perfume Genius albums, the opening track is important; the rest of Ugly Season rebels against its sensations of confinement and isolation. “Find me,” Hadreas pleads on “Herem,” the second track, his voice gossamer-like against the wavering, Arabian quarter tones of a harmonium and flute. “Lay your palm upon my heart / Unmake my name.”

When asked about this longing that recurs in his work, he paused. “I feel like I’m always sort of desperate for something. And that’s what I like to hear—I want to hear that yearning … because it’s not resolved very often for me … I feel like I’m always just sort of reaching”—he stretched out his arms—and “I think that’s a big part of, for me, what being queer was.” For him, desire is “weirdly, kind of solitary,” a feeling he has been grappling with for years. “A lot of my thoughts about desire and connection were private … They were fantasy. They were not realized. And in a way, I came to kind of like that—or at least be … conditioned to it.”

Hadreas speaks with tenderness, and it’s easy to see how this quality is the lifeblood of his music. It helps set him apart from more mainstream artists such as Lil Nas X and Adam Lambert, who tend to emphasize a queer confidence that is itself captivating and vital. Defiance is also a primal part of Hadreas’s artistic DNA. But songs such as Too Bright’s “Queen” and Ugly Season’s title track, in which he moans about being “Slick with rot / Thick as Vaseline / Knee-deep and filthy,” represent for him a “redirection of energy,” a hat trick that transforms his internal voices of shame into “the source of [his] power.” The queer body becomes an instrument of learning that contains multitudes.

Hadreas’s work is full of dualities, competing emotions and expressions. On the new “Pop Song,” Hadreas and the producer Blake Mills create an anthem of erotic transcendence against a quivering synthesizer that pays homage to Marianne Faithfull’s classic “The Ballad of Lucy Jordan.” Hadreas sketches a dissonant scene of communal sacrifice: “Our body is stretched / And holding one breath / Sharpen the palm / And sever the flesh.” The music turns darker, before shifting back to sweet, while Hadreas, in a deeper voice, duets with his own falsetto.

As we talked, the conversation turned to identity—the album’s, and his own. Ugly Season, he observed, feels “more so queer than like a gay man album. I’ve made some gay-man albums, and this feels less like that.” This comes, in part, from the record’s origins. The dance project was created with queer artists, and Hadreas said the intimate, intense collaboration prompted him to reassess how he thought about his sexuality. He was carried back years before—to the moment he identified as gay. That label “was the most of a map that I’ve ever got … The older I get, the more I realize some of it doesn’t really work for me.” On a certain level, Hadreas finds the term gay inadequate now, imprecise, and yet his own history has forged in him a fierce attachment to it. “I don’t want to give that up, because I fought for it. But it doesn’t super resonate with me either.” He said he admires the language young people have developed to navigate such complexities, and concluded that “it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot more.”

As the queer body is being policed across the country—with proposed “Don’t Say ‘Gay’” bills, legislation targeting transgender youth, rampant violence against Black trans women—Hadreas sees what he does as activism of a different sort. “Maybe it’s because I’m more confident now. I look at everybody more when we’re playing, but just seeing … all these people in a room together, and feeling like [we’re on] a little bit of a break from how fucking horrible everything is—and like a queer break, a gay break … That’s a powerful thing.”

Onstage at the 9:30 Club for his encore, “Queen,” he swathed himself in reams of ivory tulle. Gay, queer, and straight people of all ages raised their glasses, shouted their approval. They seemed to see something of themselves in him—in his searching, his gentleness, his defiance. Hadreas writhed in his cocoon, and when he unraveled himself at last, he emerged a new creation, his body radiating its own electric hymn.