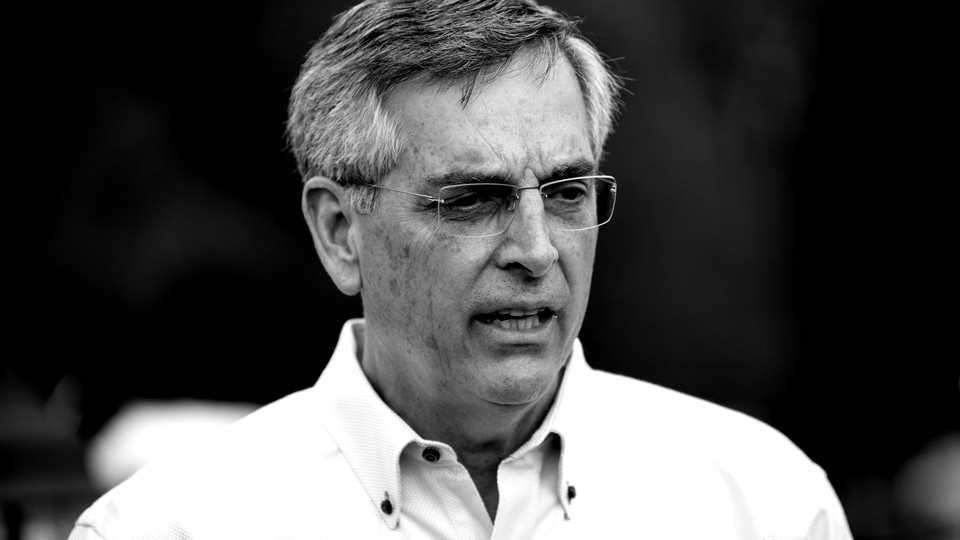

Brad Raffensperger Gets His Revenge

Brian Kemp beat a Trump-endorsed candidate last night in the state’s primary. Another Republican incumbent’s win was more surprising.

Last night’s primary in Georgia was a big, fat disappointment for former President Donald Trump: Governor Brian Kemp beat his Trump-endorsed opponent. And in a much more surprising turn of events, Brad Raffensperger, the Georgia secretary of state who refused to play along with Trump’s election-fraud fantasy, won his race too.

Raffensperger defeated Representative Jody Hice—a four-term congressman and a loud supporter of Trump’s election fever dream—by 20 points. Almost no one would have predicted this kind of comeback last year, when all of Trumpworld had trained their ire on Raffensperger. Combined with Kemp’s primary triumph, Raffensperger’s win could suggest that Trump’s influence in Georgia—and voters’ desire to relitigate the 2020 election—is waning. “Raffensperger’s election is a great barometer for the intensity of that issue with Republican voters today,” Brian Robinson, a Georgia Republican political consultant, told me. “It just shows that a lot of the air is out of the balloon. The intensity has dissipated.”

A quick refresher: On January 2, 2021—almost two months after the election had been called for Joe Biden—Trump called Raffensperger. The phone call, which Carl Bernstein later dubbed “worse than Watergate,” was an hour-long persuasion campaign. Trump flattered Raffensperger; he threatened him; he asked him to please, please just “find 11,780 votes” that would make up Trump’s margin of defeat in Georgia. Remarkably, Raffensperger, a fellow Republican and one of Trump’s earliest supporters, stood firm. Georgia’s election results were correct, he told the president, and the process had been totally aboveboard. “Well, Mr. President,” Raffensperger said, “the challenge that you have is, the data you have is wrong.”

We know about this call because someone recorded it and shared it with the press. The conversation earned Raffensperger praise from Democrats and many Republicans, but also unbridled outrage from Trump’s allies. Last year, those allies made Raffensperger enemy No. 1. Hice, a 60-year-old pastor and four-term Republican representative, was one of four candidates who jumped into the secretary-of-state race. In his campaign announcement, Hice accused Raffensperger of creating “cracks in the integrity of our election,” immediately, earning him Trump’s endorsement. Hice had proved himself to be a “staunch ally of the America First agenda,” Trump said in a statement. And Hice really had: He was one of 147 members of Congress to object to the counting of the 2020 Electoral College votes; he also shared (and deleted) an Instagram post ahead of the January 6 Capitol riot saying, “This is our 1776 moment.” In the past two years, Hice has not backed down on his election-fraud claims, even as multiple state audits led by Republican officials have failed to turn up any proof of widespread fraud. “This last election should not have been certified without proper investigation,” Hice reiterated this month in a debate. “The allegations were tremendous. They were all over the place, and they still are.”

Hice’s continued assertions of fraud in spite of all evidence are a familiar refrain in American politics these days; a song that any Republican candidate eager for Trump’s endorsement must learn by heart. Hice is just one of dozens of Republicans singing it as they run for election-oversight positions across the country. Two-thirds of all races for governor and secretary of state, along with half of all attorney-general races, involve a candidate who has publicly questioned the integrity of the 2020 election, Joanna Lydgate, the CEO of the nonpartisan States United Action, told me. Georgia is one of nine states where election deniers are running for all three of these pivotal roles. “The positions work together,” Lydgate said. “Having an election denier in any one of these positions can undermine efforts from the others.”

Raffensperger tried to strike a careful balance during his campaign. He kept to a conservative message and attempted to court the Trump base, while still refusing to go along with the stolen-election lie. He also endorsed a state voting law that instituted new regulations for mail voting and limits on the use of ballot drop boxes, among other changes. “Despite getting praise from many political corners, and many adversaries, he never started dancing to the sound of their applause,” Robinson said. In the weeks after the Trump-Raffensperger call, the secretary’s reelection chances seemed dim. But in the past several months, Raffensperger and Hice have been polling within a narrow margin of each other, with the most recent poll showing a one-point difference between them. Raffensperger had broad support: He polled better than Hice among moderate Republicans, Democrats, and independents, Andra Gillespie, a political-science professor at Emory University, told me. “Just because Trump was mad didn’t mean his endorsed candidate was going to become the far-and-away leader of the pack,” she said. “That hasn’t materialized at all.”

The Georgia results add to a growing body of evidence that Trump’s power as a kingmaker—or at least, his power to carry out a political vendetta—has weakened. Kemp angered Trump in 2020—apparently by not working hard enough to flip the election—so Trump endorsed Kemp’s opponent, fellow Republican and election-fraud-Kool-Aid-drinker Senator David Perdue. Last night, Kemp won every single county reporting in Georgia. Two other Trump-endorsed gubernatorial candidates have lost in state primaries so far this cycle in Idaho and Nebraska, and Raffensperger’s primary win adds one more notch to Trump’s losing tally.

Trump’s endorsement still gave a boost to a few of his down-ballot picks. And these results don’t necessarily mean that his fans love him any less; it might simply be that they are tired of looking backward. Georgia Republican voters interviewed this month told The Washington Post that there was probably election fraud in 2020, “yet they are exhausted by [Trump’s] singular obsession with it and are ready to move on.” Others warn against reading too much into this. Hice ran a bad campaign, Jay Williams, a Georgia GOP consultant, told me. He wasn’t running ads, and he wasn’t holding daily campaign events. “The media want to simplify everything, and it doesn’t really work that way,” Williams said. Not everything can be explained by Trump.

Raffensperger will still face a challenge in the November general election, when he’ll have to win over a broad coalition of Georgians to defeat the Democratic nominee for the post. Right now, many pivotal races in Georgia could go either way; Kemp’s forthcoming face-off against the Democratic nominee Stacey Abrams is considered a toss-up. But both history and economic conditions are on Republicans’ side this year. Come autumn, if the winds are blowing right, Raffensperger and other GOP nominees up and down the Georgia ballot will be swept into office.

Election conspiracists lost last night in Georgia, and it’s possible that the salience of the entire stolen-election narrative has declined in the state. But that isn’t the case nationwide. Election deniers all over the country are running successful primary campaigns. During the last presidential election, a handful of elected officials, including Raffensperger, chose to hold the democratic process above their own political preferences. Next time around, a different handful of people—in Arizona and Michigan and a number of other states—might choose differently.