My Mother Was Wrong

The feminists who fought for Roe wanted to believe that their victory was forever. Now their granddaughters are poised to have fewer rights than they did.

Sign up for Molly’s newsletter, Wait, What?, here.

We may have made a lot of mistakes, but at least we gave you Roe. I can’t even count the number of times my mother said some version of this to me. It was her way of explaining an earlier generation’s approach to feminism, and what she would say to me when she was trying to make sense of her own legacy. Maybe it wasn’t a normal thing for a mother to say to a daughter, but my mother isn’t a normal mother. She is Erica Jong, a second-wave feminist, a famous novelist, and a woman who throughout her career constantly grappled with what she and her cohort had accomplished and what they hadn’t.

They hadn’t managed to pass the Equal Rights Amendment. They had failed on fair pay. The too-long list of things that had once seemed possible would continue to sting for decades. During the Reagan and Bush eras, my mother felt complete despair at the way conservatism rebounded politically and culturally. She’d say she was a member of the whiplash generation, “raised to be Doris Day, yearning in our 20s to be Gloria Steinem, then doomed to raise our midlife daughters in the age of Nancy Reagan and Princess Di,” as she put it in her memoir, Fear of Fifty.

Keep in mind that my mother, like some other second-wave feminists, had huge blind spots because she had grown up wealthy and white in a blue city in a blue state. Sometimes she’d get really drunk at dinner and grumble about all the things feminists couldn’t get done for their daughters (meaning me), but she would always comfort herself with the reality that they had gotten one major thing right. My mother and all the women who fought alongside her gave my generation Roe v. Wade. They gave us the bodily autonomy we should have already had. They gave us the opportunity to choose what happens in our own uterus. It was an essential gift, and an irreversible one. Or so we thought.

Americans now see that we won’t always have the rights Roe enshrines. Indeed—according to a draft Supreme Court opinion that leaked last night, originally published by Politico—we may not have Roe for very much longer at all.

I always believed that the three justices appointed by Donald Trump would move to overturn Roe, but seeing it actually unfold, reading the words of the draft decision, provoked a generational kind of shock: “We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled.” Each line is like something out of my mother’s generation’s worst nightmare. Forty-nine years after the greatest feminist victory of the 20th century, Samuel Alito writes: “Roe was egregiously wrong from the start. Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences. And far from bringing about a national settlement of the abortion issue, Roe and Casey have enflamed debate and deepened division.” It’s worth pointing out here that in 1973, five years before I was born, when women had far fewer rights—when they couldn’t even get a credit card without the permission of their husband or father—Roe was decided 7–2, with five Republican-appointed justices in support. The world has become profoundly more pro-choice than it was in 1973; even Catholic countries like Ireland have legalized abortion. Yet here in America, the clock is spinning backwards with stunning and terrifying speed.

It’s not that my mother’s generation hasn’t feared this outcome before. Six days after the 1989 swearing-in of president George H. W. Bush, my mother wrote in The New York Times, “Now that the Supreme Court has agreed to hear an attack on Roe v. Wade, it is painfully apparent that two decades of feminist achievement can be swept away with one wave of a judicial or Presidential hand. Women and men who thought all this was settled long ago, who naively assumed that women’s bodies would never again be political battle grounds, have had to wake up and take notice.” Sixteen years later, in October 2005, Bush’s son would appoint the man who would write the draft opinion that proves how naive we have been.

“The inescapable conclusion is that a right to abortion is not deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions,” Alito writes. But that’s not really true. Forty-nine years encompasses a lot of history and tradition. I am 43 years old. I have never lived in an America without Roe. I have never lived in a country where more than half of the population does not have agency over their own body. It appears that I will live in that world starting in June, and so will 167 million other women.

So what now? The internet is a sea of enraged comments. Online activism can be powerful—but it is not enough. A CNN poll from January shows that only about 30 percent of Americans want Roe overturned. The large majority of Americans don’t want this. And now is the time for them to exercise a right we still have—the right to peacefully protest.

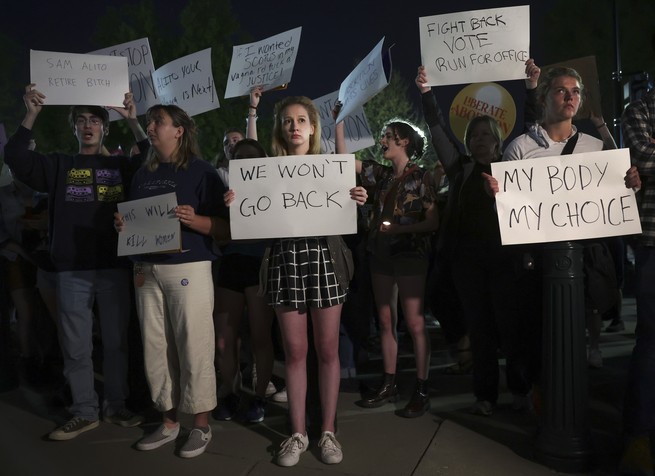

Those who support Roe’s protections must show lawmakers and justices that they are about to do something very unpopular. Last night, peaceful protesters gathered in front of the Supreme Court to chant, “Hey hey, ho ho, Sam Alito’s got to go.” By 11 p.m., hundreds of people had assembled. But hundreds of people can’t do this alone. This leaked document should become a rallying cry. The opinion is still a draft. We don’t know with certainty where all the justices will land. Democrats still control Congress, and the presidency. There are still things they could do. Congress can legislate; President Joe Biden can use his executive powers.

My mother is 80 now. She doesn’t write much anymore. But the term whiplash generation feels more apt than ever. She is about to watch her granddaughter grow up in a world without the rights she secured for herself, and for her daughter. Today, we have a glimpse of history not yet written. A seismic change in America is coming, and it is coming quickly. But it isn’t too late. Not yet.

Listen to the writers Molly Jong-Fast, Mary Ziegler, and David French on Radio Atlantic: