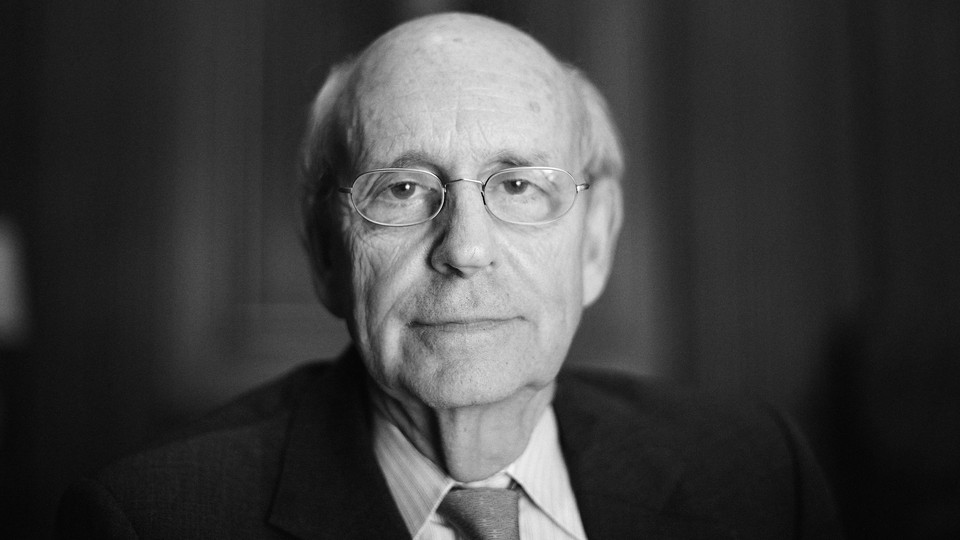

The Court Loses Its Chief Pragmatist

With the upcoming retirement of Justice Stephen Breyer, the country moves into a more ideologically divided future.

Last spring, during an online civics class I teach at the National Constitution Center for high-school students, I asked Justice Stephen Breyer about the values of compromise, consensus, and intellectual humility that he has championed throughout his career, as a Senate staffer for Ted Kennedy, an appellate judge, and a Supreme Court justice.

“I saw Senator Kennedy do this all the time,” replied Breyer, who announced his retirement from the Supreme Court today. “He was a Democrat—Republicans disagreed with him strongly—but if you need that Republican support, you say, ‘What do you think? My friend, what do you think?’ Get them talking. Once they start talking, eventually they’ll say something you agree with.”

Breyer’s optimistic conclusion—“you can do pretty well by trying to get people together in a thousand different ways”—was criticized by some Democratic partisans, who also called him naive for opposing court packing, a position he asserted in a recent speech at Harvard Law School. In his Harvard lecture, since published as a book, Breyer argued that viewing judges as nothing more than “politicians in robes” would threaten the Court’s nonpartisan legitimacy. “Breyer needs to grapple with the possibility that Democrats increasingly perceive the Court as a partisan institution because it has become a partisan institution,” one critic wrote.

Breyer’s constitutional vision as a justice—his commitment to temperance, flexibility, compromise, and restraint—had mixed success at the Supreme Court in the term that ended last June. Although it issued some polarized decisions along 6–3 partisan lines, most notably in a case limiting the Voting Rights Act, the Court also issued relatively narrow and nearly unanimous decisions, several written by Breyer himself, in cases that upheld the Affordable Care Act, protected the free-speech rights of students, and defended the religious-liberty rights of Catholic social-service agencies.

This term, however, in its pitched battles over abortion, gun rights, vaccine mandates, and now affirmative action, the Court has risked dividing 6–3 in precisely the way that Breyer tried to avoid. The ability of John Roberts’s Court to maintain its nonpartisan standing in future terms will depend on whether it continues to embrace the pragmatic moderation that Breyer practiced during his 27 years on the Supreme Court or whether it puts ideological purity above institutional legitimacy.

Hours after President Bill Clinton nominated him to the Court on May 17, 1994, Breyer made his commitment to constitutional pragmatism clear. “The Constitution and the law must … work as a practical reality,” Breyer said in the Rose Garden. “And I will certainly try to make law work for people, because that is its defining purpose in a government of the people.” Breyer stated the values that informed his approach to the Constitution with similar clarity in an essay for The Atlantic in 2007: “The future of the American constitutional idea … is the future of a shared set of ideals. This implies a shared commitment to practices necessary to make any democracy work: conversation, participation, flexibility, and compromise.”

In his 1994 confirmation hearings, Breyer attributed his sense of optimism about the possibilities of democratic government to his father, who worked as a lawyer and administrator for the San Francisco public-school system for 40 years. “He was a very kind, very astute, and very considerate man,” Breyer said. “He and San Francisco helped me develop something I would call a trust in, almost a love for, the possibilities of a democracy.”

It’s fitting, therefore, that one of Breyer’s most significant majority opinions for the Court emphasized the central connection between public schools and education for citizenship in American democracy. In an 8–1 decision earlier this month protecting the right of a public-high-school student to curse on Snapchat after she failed to make the cheerleading squad, Breyer wrote: “America’s public schools are the nurseries of democracy.” The memorable phrase evoked two of his heroes: Justice Louis Brandeis, who called the states “laboratories of democracy,” and Alexis de Tocqueville, who called the institution of the American jury a “gratuitous public school, ever open in which every juror learns his rights.” It also reflected Breyer’s view, expressed in his 2005 book, Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution, that judges should interpret the Constitution to promote its “democratic objective” of encouraging “participatory self-government.”

In addition to promoting democratic participation, Breyer believed that judges should interpret the Constitution to earn the public’s confidence, so that Americans would follow their decisions even when they disagreed with them. In his 2010 book, Making Our Democracy Work, he offered two principles, drawn from experience and history, that the Supreme Court should adopt to maintain its legitimacy. The first was that the Court should reject a jurisprudence of rigid original understanding, instead viewing “the Constitution as containing unwavering values that must be applied flexibly to ever-changing circumstances.” The second was that the Court should “take account of the role of other governmental institutions and the relationships among them.” This means that judges should think not only about the impact of their decisions on the other institutions of government, but also about the way the public will perceive the legitimacy of the courts themselves.

This nuanced approach often led Breyer to champion judicial restraint: According to a 2005 study of William Rehnquist’s Court, Breyer was the justice least likely to strike down federal laws on constitutional grounds. His restraint was based on his belief that other, more democratic government institutions—including local school boards, state legislatures, and executive agencies—should be free to debate and interpret the Constitution on their own.

When the students in my NCC class asked Breyer to list his favorite opinions he had written on the Supreme Court, he offered two dissents. One of them, in 2007’s Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District, emphasized that “the Constitution does not authorize judges to dictate solutions” to problems like how to desegregate Seattle public schools. Instead, Breyer wrote in his 76-page dissent, “the Constitution creates a democratic political system through which the people themselves must together find answers.” In Breyer’s view, judicial restraint encourages rather than thwarts democratic self-government.

But Breyer was not inflexibly devoted to judicial restraint. The other favorite opinion he listed was his 41-page dissent in Glossip v. Gross, a 2015 death-penalty case in which Breyer argued that “almost 40 years of studies, surveys and experience strongly indicate” that the death penalty cannot be administered in a way consistent with the Constitution. Breyer’s opinion identified three fundamental constitutional defects of the death penalty—“(1) serious unreliability, (2) arbitrariness in application, and (3) unconscionably long delays that undermine the death penalty’s penological purpose.” His dissent emphasized empirical evidence and real-world consequences, rather than a rigid adherence to either judicial restraint or the original understanding of the Constitution. It ended with appendices showing the numbers of death sentences and executions from 1977 to 2014, year-by-year percentages of the U.S. population living in states that had recently conducted an execution, and maps showing the U.S. counties that administer the death penalty.

Originalists argue that constitutional pragmatism is unprincipled because it is willing to consider the practical consequences of decisions in the real world, rather than following text and history no matter where they lead. But Breyer argues that because a justice’s political philosophy inevitably influences his or her constitutional philosophy, it’s best to be transparent about the fact that all judges balance competing values, which are guided by their background and worldview.

“Suppose you think deeply that free enterprise is the secret of success in this country. Or suppose you deeply think that at least some moves toward socialism are surely justified and will help,” he told the NCC students. “Is that a political view, or is that a philosophical view? Is that political philosophy, or is that real politics? Well, I think those things are often hard to separate out. And I can’t say that things like that never influence a decision.” Breyer told my students to remember Benjamin Franklin’s caution that a republic can be sustained only by the confidence of the people over time. “Franklin said, ‘Hey, this is a document here. And it’s not just democracy. It’s not just human liberties. It’s not just organizing the government. It’s also something that’s going to work, and it’s going to work for a long time,’” Breyer emphasized. “And you think about that when you have certain difficult constitutional cases, and you try to choose something that moves in the direction of something that will work for a long time, among other things. Now that’s a rough description of what I mean by pragmatism.”

Because constitutional pragmatism is hard to sum up on a bumper sticker, and because it requires balancing competing values that sometimes clash, Breyer’s greatest influence may have been behind the scenes at the Supreme Court. He tried throughout his tenure to encourage compromise between the conservative and liberal wings of the Court, forging an alliance of centrists anchored first by Sandra Day O’Connor and then by Chief Justice John Roberts. The fact that Roberts shared Breyer’s commitment to preserving the Court’s institutional legitimacy by avoiding 5–4 splits along partisan lines gave Breyer and his similarly pragmatic colleague Elena Kagan an important role after O’Connor’s retirement shifted the balance of the Court to the right. Perhaps their most notable success was the first Affordable Care Act case, in which, according to the journalist Joan Biskupic, Breyer and Kagan “were willing to meet [Roberts] partway.” After Roberts changed his initial vote, which had been to strike down the individual mandate of the ACA, Breyer and Kagan changed their initial votes, which had been to uphold the requirement that states would lose federal funding unless they extended Medicaid coverage to people near the poverty line. Although conservative and liberal critics viewed this horse-trading as unprincipled, Roberts, Breyer, and Kagan recognized that unless citizens perceived the Supreme Court as above partisan politics, they would refuse to accept decisions with which they disagreed, threatening the rule of law that is the keystone of American democracy. “It’s taken a long time to earn legitimacy in the sense that people will follow [judges’ interpretation of] the laws,” Breyer told the NCC students. “The rule of law is: Follow it, otherwise you won’t have a rule of law.”

From the beginning of their tenure, Roberts and Breyer recognized that their ability to forge bipartisan compromises depended on the willingness of their colleagues to share their commitment to pragmatic compromise and institutional legitimacy. That’s why it seemed significant last term that the newest justices, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, joined them in upholding the ACA for the third time, over the dissents of Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch.

After the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Breyer became the senior liberal associate justice, which gave him the power to assign majority opinions when the chief justice was in dissent. Breyer used his authority to reach out to Barrett, assigning her the majority opinion in a Fourth Amendment case regulating the ability of police to search computer databases, over the dissents of Roberts, Alito, and Clarence Thomas. When I asked Breyer what he had learned during his long tenure, he replied, “I’ve learned that I have less power to persuade people than I thought I might.” The high unanimity rate and unusual ideological alliances last term are a tribute to the ultimate persuasiveness of his nonpartisan vision. But, as Breyer recognized, any consensus seems very fragile as the Court takes on the most polarizing issues, such as abortion, gun rights, and affirmative action, where the justices are less open to persuasion.

Breyer said over the years that justices, including himself, are less likely to compromise in highly charged cases about which they have strong, preexisting views. Describing the “loneliness and a kind of anxiety” that come with judicial independence, he told my NCC students, “It’s complicated by the fact [that] if you’re dealing with eight other colleagues, you want to reach an opinion, and you better be willing to compromise, and how much compromise? How much? And when? And there is no calculus that gives you an answer to that question. That’s internal.” This term and next, the sorts of compromises that Breyer championed throughout his career appear ever more elusive. Breyer insisted that if the Court abandons the pragmatic centrism that he, along with Justices O’Connor and Roberts, embraced, the Court’s most precious asset—public legitimacy—will suffer.

In deciding whether to overturn Roe v. Wade or other well-established precedents, Breyer suggested that justices should remember that a connection exists between the stability of precedents and the Court’s democratic legitimacy. “Law is, in part, about stability,” he told my NCC students. “Part of what it’s doing is to allow people to plan their lives … And the law might not be perfect, but if you’re changing it all the time, people won’t know what to do. And the more you change it, the more people will ask to have it changed.” At the oral argument in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, in cautioning his colleagues about the danger of overturning Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, Breyer read aloud, with great emphasis, the following sentence from the Court’s decision: “To overrule under fire in the absence of the most compelling reason, to reexamine a watershed decision, would subvert the Court’s legitimacy beyond any serious question.” Once the public concludes that the justices are “just political, you’re just politicians,” Breyer cautioned, “that’s what kills us as an American institution.”

Squandering the public’s trust in the rule of law and the institutions of government is a threat to the union, as the Founders recognized. At the Constitutional Convention, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, the two greatest advocates of a strong union, acted as what the historian Edward J. Larson, in Franklin & Washington: The Founding Partnership, calls “enlightenment pragmatists at heart,” changing their positions on several issues in order to ensure the ratification of a strong and flexible Constitution that would allow Americans to resolve their differences peacefully and democratically. Both believed that the republic would survive only if American citizens and their representatives were able to use their powers of reason to moderate their selfish emotions and partisan passions, so that they could be guided by the classical virtues of temperance, prudence, fortitude, and justice. In other words, individuals have to learn to govern themselves before they can engage in self-government with others. These founding virtues are the ones Breyer has embodied throughout his career, in his jurisprudence, and in his kind, temperate, and decent character. A lifelong teacher and learner, he is a model of the civic virtue that the Founders hoped for.