In 2013, Barack Obama hosted Ruth Bader Ginsburg for lunch in his private dining room, hoping to gingerly raise the possibility of her retirement while he still occupied the White House and Democrats still controlled the Senate.

She got the message. She also ignored it. Ginsburg didn’t suffer much of a reputational hit for her defiance, at least not at the time. The woman who’d been barred from one of the reading rooms at Harvard Law when she was a student, the woman who’d been denied a clerkship with Felix Frankfurter partly because she was a mother—of course she wasn’t going to daintily hang up her jabot just because the boys were telling her to. For years, she’d stood outside the doors of their institutions with an ice pick, chip-chip-chipping her way in. She’d bested three types of cancer. She did daily sets of planks. And now they were telling her it was time to go? Really?

In hindsight, we know that this decision had catastrophic consequences for the causes to which she devoted her career. RBG—Washington’s least likely crossover star, a super-signifier of all things fabulously feminist and liberal—may, with time, inadvertently live up to the Notorious appended to her name, in spite of her extraordinary accomplishments.

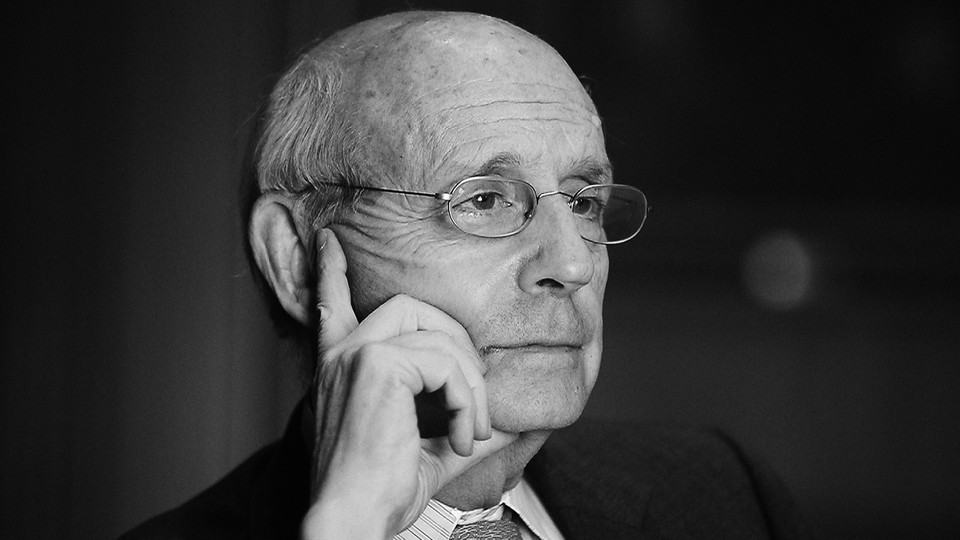

Which brings us to Justice Stephen Breyer.

At 83, he has not announced his retirement. Even though he finds himself in the functional equivalent of that Obama-Ginsburg moment in 2013, with a Democrat in the White House and Democrats in control of the Senate. Even though Joe Biden’s approval rating is at 41 percent. Even though Democrats just lost the governor’s mansion in one blue state (Virginia) and barely held on to it in another (New Jersey). Even though congressional Democrats are currently careening toward a 2022 midterm wipeout, with Republicans testing better on generic ballots than they have in 40 years.

Two years ago, Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a dean at the Yale School of Management and the author of The Hero’s Farewell, memorably told me that when CEOs manage to retire in a timely fashion, it’s frequently because they have a negative role model in mind, an uneasy memory of some muckety-muck who grossly overstayed his or her welcome.

So why on earth hasn’t Ruth Bader Ginsburg served as a cautionary tale?

Only Breyer can say, of course. For all we know, she has served such a role, and he simply hasn’t yet announced his plans to retire by the end of June, when the Court typically goes into recess. (My money is on this option, actually—that he’ll say something in January.) But part of me, I’ll confess, understands why retirement has recently become such a vexed subject for Supreme Court justices. It places the onus on them.

The Supreme Court offers a rarity in American employment life: a sinecure. The average American now lives to be roughly 78, and plenty of fabled justices have lived and served far beyond that (including Thurgood Marshall, Louis Brandeis, and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.). Why, if you’re still healthy, would you voluntarily step away from a job you’re still enjoying? To do so violates not just your own intuition, but your own self-concept—one that’s quite justifiably predicated on the notion of your own competence. “My senior colleague, Justice John Paul Stevens, he stepped down when he was 90,” Ginsburg told CNN in 2018, “so I think I have about at least five more years.”

When we repeatedly admonish older public officials to retire, we’re erasing their individuality and turning them into actuarial statistics, which no matter how you look at it is rather ugly—no one likes to be told that their mortality is becoming a problem. In the most practical sense, we’re asking them to void their calendar, to replace something with nothing at all.

I keep thinking about the fact that Ginsburg was a widow when she was being pressured to retire. Marty, the love of her life, had died in 2010, and here she was, being asked to wake up each morning and not go to work. How many older people consider their work life essential to their well-being? (There’s no shortage of data about this, at least for those who have been involuntarily put out to pasture. Their mental health unambiguously takes a dive.)

Walking away is especially challenging for those whose identity is entirely reliant on the institution they serve. Vermont’s Patrick Leahy, 81, may have just announced his plans to retire from the Senate, but Iowa’s Chuck Grassley, 88, is planning on running for his eighth term in 2022, and California’s Dianne Feinstein has filed paperwork to run again in 2024, when she’ll be 91. (Our Senate is now the oldest it’s been in our history. Twenty-three members are in their 70s.)

“If you’re a violinist, you can play in retirement,” Sonnenfeld told me in that same conversation. “But if you’re a conductor, where your identity depends on the group, you can’t really replicate that in retirement.”

So what to do?

Roughly a decade ago, when some of the most senior faculty at Johns Hopkins University were showing a reluctance to retire, the dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, Katherine Newman, had an inspired idea: Why not start a dedicated academy for emeritus faculty, where they could still organize conferences, do research, and enjoy the fellowship of their peers? “Everybody I talked to said it wasn’t the money they were worried about,” she told me. They’d paid for their homes; their kids were launched; they had old-fashioned pensions. “They weren’t interested in teaching or burning up the landscape with more publications,” she continued. “It was their identity they couldn’t let go of, the purpose, the engagement. So the Academy at Hopkins was born to retain those ties.”

This wasn’t some hollow, mollifying gesture, the creation of this academy. Newman put it right next to the president’s house. She gave all the professors a small budget to do research and attend conferences. The academy itself had a budget to organize conferences and bring in visiting scholars. By the time it was up and running, roughly a dozen professors had left their department and joined. “Just because you move on,” said Newman, now the system chancellor of academic programs at the University of Massachusetts, “doesn’t mean you move into the shadows.”

Is this a perfect parallel? No. But it isn’t far off. Judges, like academics, consider their profession a calling. They do the work because they love it and find it meaningful, not for the money. It’s true that judges have power, something that academics do not, except within their own fiefdom. But federal judges also have an option just like the Academy at Johns Hopkins, one that helps them retain their esteem and power: They can hear cases “by designation” on circuit-court panels around the country. (Sandra Day O’Connor has done exactly this, in fact.) It essentially means that they’re guest stars or pinch hitters for a day. Does this arrangement have the same glamour or power as the highest court in the land? No. But is it a way to remain engaged? Yes. And maybe to take one extra lap around the rink, gathering roses.

In an August interview with The New York Times’ Adam Liptak, Breyer suggested that he understood how dire the consequences would be if he retired at the wrong moment, recalling “approvingly” something that the late Justice Antonin Scalia had told him, which is that he didn’t want a successor who’d reverse everything he’d worked so hard to achieve.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that Breyer made a revealing confession during that same interview: “I don’t like making decisions about myself.” It was, at first blush, a strange thing for a justice to say. All they do is make decisions. They are deciders by profession. But about myself was the operative phrase in this case. The responsibility of making a choice about his own professional future was such agony to Breyer that he implied he’d prefer if the decision were made for him—by term limits, specifically. “It would make my life easier,” he admitted.

Of all the reforms that Biden’s bipartisan commission on the Supreme Court is entertaining, it so happens that term limits are the most popular. But for now, the decision to step down remains Breyer’s to make, and every day he doesn’t make it poses a risk to his legacy. The Democratic majority in the Senate isn’t really a majority at all, but a tie. Its power could all unravel in a trice.

If Biden isn’t able to get Breyer’s successor confirmed by the Senate, it’d be a disaster, not just for Democrats, but for American democracy in general, imperiling the very legitimacy of the Court. We might like to believe that the law is the law, untainted by ideology. But instinctively we know that it isn’t: A justice’s interpretation of the Constitution often depends on their politics. Voters cast their ballot for president with that in mind. But this June, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell refused to say whether a Republican Senate would confirm a Biden nominee to the Court in 2023, should the GOP have the good fortune to recapture that chamber, and he said it was “highly unlikely” that a Republican Senate would confirm a Biden nominee to the Court in 2024.

As it is, the Supreme Court hasn’t had a majority of Democratic-appointed justices since before Amy Coney Barrett was born, noted Richard Primus, a professor at the University of Michigan Law School, in a recent email.

“If, over time, judicial decisions are made partly by the nominees of each party, then both parties feel they have a stake in the institution,” he added. “I sit still when the refs make close calls your way because you sit still when they make close calls my way.” But if decisions are made only by one party’s appointees, he wrote, “the other party’s sense that the game is fair is going to take a hit—and even more so if that party has won the popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections and still has no prospect of appointing a Court majority.”

What Primus didn’t say—but of course it was implied—is that Democrats actually lost two of those seven presidential elections, even though they won the popular vote. A 7–2 conservative Court, with two justices owing their seat to a Senate Republican leader hell-bent on obstruction, would be one more step toward minoritarian rule in a country that’s already slouching in that direction. According to a recent analysis in the Times, Republicans could win back the House of Representatives in 2022 based on redistricting changes alone; according to Vox, we now live in a country where the Democratic half of the Senate represents 41,549,808 more people than the Republican half.

This problem has no short-term solution. Harm reduction is about the most we can ask. Breyer can play a modest role in keeping our institutions from disintegrating completely into dust. Asking him to retire may be harsh, even unfair. But if he can summon the will to make this choice, it’ll be one of the most important decisions he’s ever made.