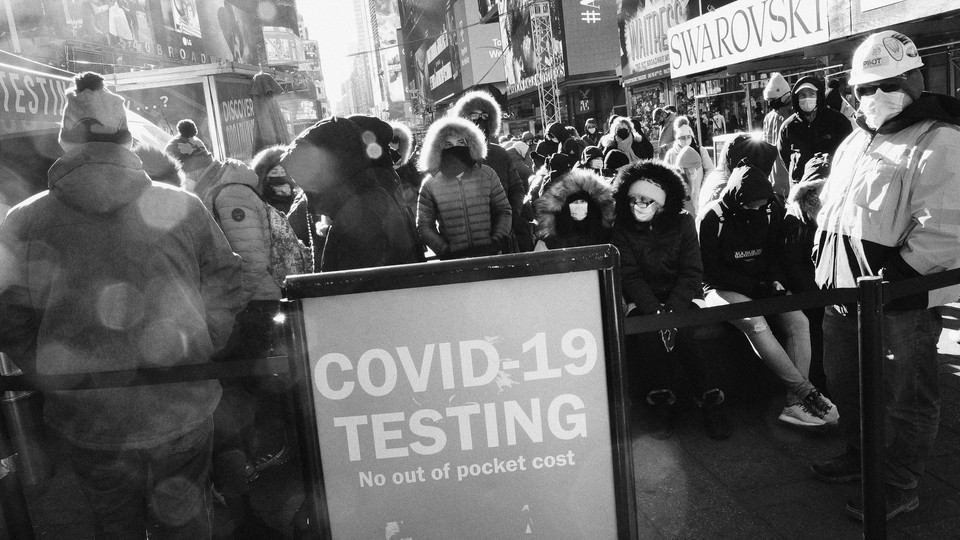

As the Omicron variant sprints to dominance across the United States, the country’s ability to track the resulting infections is about to evaporate. There are multiple reasons for this. The first is that the United States can’t do enough tests. Where cases are rising quickly, demand has already outstripped testing capacity, leaving people standing in long lines, many in bad weather. CDC rules specify that the only way a COVID-19 infection gets counted as a confirmed case is if it’s identified via PCR test or genomic sequencing. Booked-up testing sites and clogged test-processing labs—and the necessary shift toward rapid antigen tests, which can’t officially confirm a case even when their results are reported to public-health authorities—mean that many infections simply won’t get counted.

But even where tests are being performed and processed, Americans are about to lose their ability to see the results, thanks to the way holidays interact with COVID testing and data reporting. On and around major holidays, thousands of people whose labor makes testing and data-reporting pipelines function go home. As a result, testing slows, and reporting through the various levels of public-health agencies tanks, along with the last-mile work of getting the data into public view. This effect produces the illusion that cases are dropping, or are dropping faster than they are—and tragically, this false decline in the numbers comes just as the risk of transmission increases, because holidays also involve a rise in large get-togethers with friends and family.

Later, when people return to work and crunch through testing and data backlogs, the data will recover (though only to a limited degree; lots of people who couldn’t get a test because of shortages and holiday slowdowns simply won’t ever get one). The sudden arrival of the backlogged data will in turn produce a deceptively sharp spike that looks like an even more sudden increase in cases. With two major holidays in a row, the artificial drops and spikes produced by reporting delays can run together, creating a long period of confused data. Last year the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic found that after the twin disruptions of Christmas and New Year’s Day, holiday data distortions extended for weeks into the new year.

Abundant at-home rapid tests could have helped with the testing crisis, at least for people trying to determine whether the cold they have is COVID and they should stay home from a family gathering. But getting a rapid test is now nearly impossible in many areas. This is because the U.S. government has never taken testing seriously enough to produce and distribute sufficient tests to handle the pandemic waves that keep coming. Moreover, the Biden administration’s promised 500 million at-home tests won’t arrive in time for the holidays, and the intended volume is far too low to address the country’s testing demand.

The result of these cascading testing and data problems is that just as Omicron transmission really takes off in the United States, the large-scale movement of the pandemic is becoming impossible to discern, while at the scale of the individual, millions of people will be unable to know whether they have COVID. Case numbers will be artificially reduced, along with testing counts. And, at the same time, many people will be unable to get the rapid tests required to tell whether they’re likely to be infectious. Just about the only numbers that might be reliable throughout the holiday disruptions and testing collapse are those in the hospital-utilization data set from the Department of Health and Human Services, which powers visual tools such as The New York Times’ extensive county-level hospitalization maps and trend charts. Of course, hospitalization numbers tend to trail case numbers because people take time to become seriously ill. Far from being an early-warning system, rising hospitalization numbers are a record of things—lives, outbreaks, and attempts at public-health interventions—that have already gone badly wrong.

As the country heads into its second pandemic winter in the teeth of a ferociously quick variant, the safest assumption is that Omicron is going to do here what it’s been doing elsewhere. Infections are going to spike, whether U.S. institutions can track them or not. Lots of people are going to get sick. And until the holidays and the testing crunch are behind us, no one will know what’s really happened.

In this information vacuum, some of us will tend toward caution and others toward risk. By the time Americans find out the results of our collective actions, the country will have weeks of new cases—an unknown proportion of which will turn into hospitalizations and deaths—baked in. In the meantime, the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker Weekly Review has wished us all a safe and happy holiday and gone on break until January 7, 2022.