Diplomacy Alone Can’t Save Democracy

Domestic actors, not global summits, drive democratization.

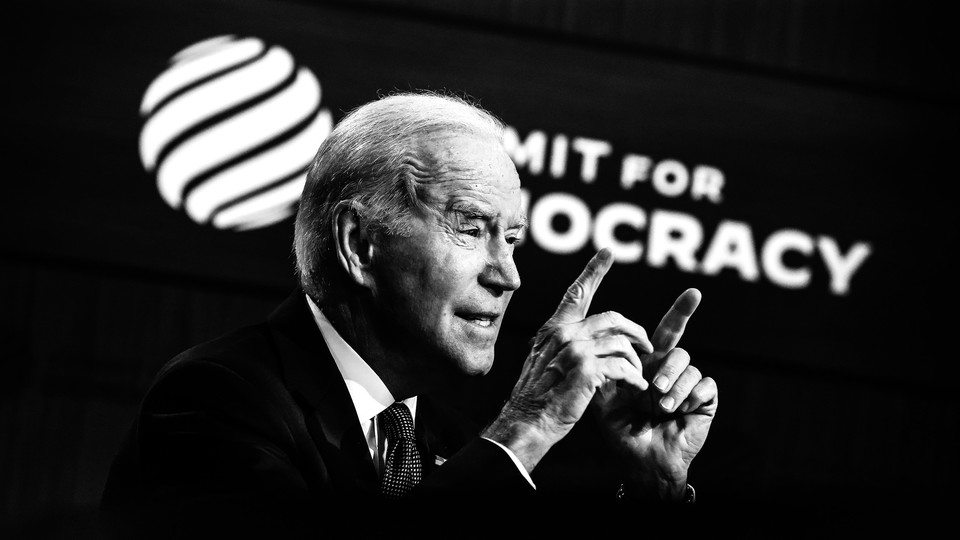

As Joe Biden convened his virtual Summit for Democracy this week, he warned that democratic erosion represents “the defining challenge of our time.” He isn’t wrong. Democracy is under siege, and this year has been marked by contested elections, coups, and autocratic brazenness. This was the fifth consecutive year in which the number of countries moving in the direction of authoritarianism outpaced those moving toward democracy. Among the backsliders are some of the world’s largest democracies, including Brazil, India, and the Philippines. The bad guys are winning. And given Donald Trump’s persistent refusal to acknowledge his 2020 loss, even the United States’ own democracy is at risk.

As a candidate, Biden pledged to make renewing democracy a cornerstone of his foreign policy, in part by bringing together leaders and representatives from the world’s democracies to address authoritarianism, fight corruption, and promote human rights. By the end of the summit, which wraps up today, participating governments are expected to make commitments to shore up democracy at home and abroad. The status of those pledges is set to be reviewed at a follow-up gathering next year.

Reversing democracy’s global decline is a tall order for what is effectively a think-tank exercise. The summit faces some glaring obstacles, including the questionable sincerity of its more illiberal participants and America’s weakened credibility on the topic at hand. Perhaps the most fundamental challenge is the question of whether diplomacy can meaningfully achieve what Biden has set out to do.

Of the more than 100 countries invited to participate in the summit, the majority represent strong democracies. But the guest list also features many leaders who are responsible for driving the democratic backsliding that prompted the summit in the first place, including India’s Narendra Modi, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, and the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte. Together, they’re in charge of some of the countries that have seen the steepest democratic decline. Indeed, more than a quarter of the countries on the summit’s roster were deemed only “partly free” in the democracy watchdog Freedom House’s latest “Freedom in the World” report. Three invitees (Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Iraq) are not considered free at all.

In deciding which countries would be included in the summit, the Biden administration sought to ensure that “a diverse slate of democracies” was represented, a State Department spokesperson told me. A more cynical reading of the guest list would be that the U.S. invited a number of countries too important to snub but where democracy is on the decline, such as India and Poland.

Irrespective of which countries are involved in the summit or how highly they rank on the democratic scale, preventing and reversing global democratic erosion will not be easy for diplomacy to tackle on its own. Democratization is a process that usually takes place within countries, not among them. Some of the gravest threats to democracy are internal: distrust, polarization, voter suppression, and partisan institutions. Diplomatic pressure can encourage and promote more democratic practices, but it is not what drives democracy forward.

Domestic actors and movements play the biggest role in defending—or destroying—democracy. And for good reason: The foundations of healthy democracies, including voting access and civil liberties, are largely domestic matters. Poor access to public services, rising inequality, and declining material prosperity can also lead to democratic decline, experts have warned. “Direct players,” including the political establishment, civil society, the press, and the private sector, are most responsible for protecting democracy, according to the Brookings Institution’s Democracy Playbook, a set of 10 recommendations the think tank updated this week ahead of the summit. Foreign governments’ and international institutions’ role in promoting democracy is largely limited to supporting civil society and, where applicable, making financial aid and trade contingent on democratic outcomes. Although diplomacy can complement domestic efforts, it’s not a sufficient replacement for “a powerful and genuinely domestic movement to hold public figures and institutions accountable to democratic rules and principles,” the Brookings report notes.

Diplomacy is “a critical ingredient in the mix of tools that can have a beneficial effect,” Norman Eisen, the former U.S. ambassador to the Czech Republic and a co-author of the Brookings report, told me. But ultimately, “the fight against illiberalism, the battle for democracy, has to be led and won by the people and the political leaders of a nation.”

In some ways, Biden’s summit takes this reality into account. By encouraging participating countries to propose their own targets, and by involving activists, journalists, and other members of civil society in the discussion, he is effectively encouraging countries to bear the brunt of the work themselves. This allows leaders to tailor their pledges to their own country’s needs, but also prevents the U.S. from being seen as dictating how other democracies should act—something that would unlikely be appreciated coming from a country with its own backsliding problem. The United States’ questionable authority on this subject isn’t lost on the Biden administration, which is approaching the summit from a “position of humility,” a senior administration official told reporters on Tuesday. Within the past year alone, 19 U.S. states have enacted laws making it more difficult for Americans to vote. The fight to install partisan loyalists in key election posts ahead of future elections is already being waged across the country.

“We have this archaic Electoral College; we’ve got this system that’s increasingly gerrymandered so that members of Congress can basically choose their own voters instead of the other way around; we have a system that empowers a minority party to act like a majority party, and that is being more deeply entrenched,” Matt Duss, Senator Bernie Sanders’s foreign-policy adviser, told me. “If we’re talking about protecting and preserving democracy, there’s a very real question of what have we actually been doing here at home to protect our own?”

Another challenge for the summit is the overarching narrative that the democracy crisis is inherently geopolitical and rooted in a contest between the world’s democracies and authoritarian states, rather than an internal conflict within democracies themselves. By fixating on the former, and the threats posed by maligned external actors, democracies risk overlooking more insidious threats that reside within, in the form of growing polarization, inequality, and distrust in the idea that democracy can deliver for people’s needs.

“The threats to democracy are much less from the autocracies than the ability of democracies to make our systems work,” Bruce Jentleson, a public-policy and political-science professor at Duke University and a former foreign-policy adviser to the Obama and Clinton administrations, told me, noting that although external threats such as disinformation campaigns are real, “the receptivity to that is because our systems aren’t working.” While Russia and China would no doubt cheer future efforts to subvert U.S. democracy, they can’t cause any more damage than Americans have already proved willing to cause themselves.

Laying the groundwork to save democracy is a lofty goal for any summit, much less an online one spanning two days. But whether Biden’s will be remembered as a net positive will ultimately hinge on whether it can yield tangible commitments. The best proof of concept would be for the U.S. to return to next year’s follow-up having taken the necessary steps to strengthen American democracy and prevent the constitutional crisis of 2020 from repeating itself. But this summit isn’t likely to galvanize U.S. lawmakers to take this matter seriously any more than it is to compel leaders elsewhere to act. Democratization begins at home.