The Home Is the Future of Travel

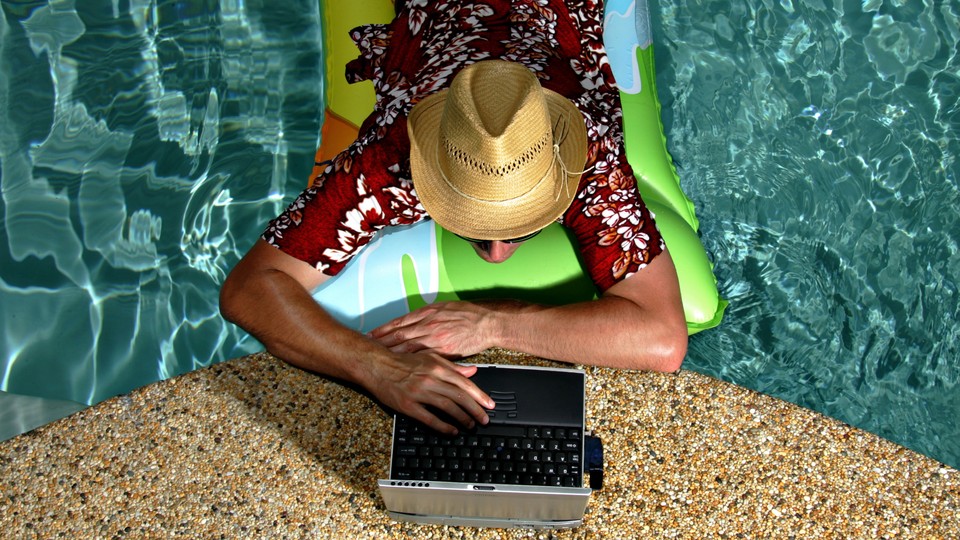

The CEO of Airbnb thinks the lines separating life, work, and vacations will keep getting blurrier.

Work and life are undergoing a “Great Convergence.” The once-solid boundaries between our jobs and our leisure are getting leakier.

Knowledge industries—including media, marketing, and law—have for decades collapsed the distinction between work skills and social skills. The same schmoozy behavior that can win friends and influence people can also win business and influence promotions. Computers, where Excel documents intermingle with shopping tabs, blend work tools and personal tools. And remote work—the ability to do a job not only from home but from anywhere—mashes up our work time and leisure time, erasing the spatial differences between many of our weekdays and weekends.

You can see this convergence most clearly in our houses. As recently as the 1800s, the home was everything—where Americans worked, and slept, and cooked, and ate, and raised children, and worshipped. For most people, there was no commute; there was no office, or factory. And the agrarian economy ruled out vacations for most families. Then, in the past 150 years, the industrialized world drew sharp lines between life, work, and leisure. It was a period of divergence rather than convergence. Home, work, and hotel meant three different places.

But we’re going back to the past. “Travel, life, and work are blurring together again,” Airbnb’s chief executive, Brian Chesky, told me. He said the home-rental company is seeing firsthand a new kind of travel habit becoming mainstream, in which work time is leaking into vacation weekends and vacation weekends are leaking into the workweek. It is the rise of the work-vacation: the workcation. For a long weekend, or a week, or even several months, you can make a temporary home in the mountains or on the beach, without taking any time off.

Naturally, Homes are the future of travel is exactly what you would expect the chief executive of Airbnb to say. But he has the numbers to back up that view. Last week, we spoke about remote work, the future of travel, and Airbnb’s business. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Derek Thompson: You wrote that with the sustained increase in remote work for millions of white-collar workers, “we’re on the verge of a revolution in travel.” What’s your thesis?

Brian Chesky: If Zoom is here to stay, then remote work is here to stay. For tens of millions of people, they’re not as tethered to one location. As a result, there is newfound flexibility for millions of people when it comes to work and travel. Not everyone, to be clear. But millions of people can embrace a more flexible work policy that allows them to move around in new ways.

Thompson: Since the pandemic started, what have been the most dramatic shifts in the way people are using your platform?

Chesky: The most compelling statistic for me is the number of people who are using Airbnb for long-term stays. Twenty percent of our nights booked now are for 28 days or longer. Half of our stays are for a week or longer. These are big increases from before the pandemic, and I think it’s related to the fact that people don’t have to go back to the office.

Another data point we’re seeing is an increase in people traveling with pets, as people are staying longer. Use of the Wi-Fi filter on Airbnb has increased by 55 percent since before the pandemic, so people obviously care more about their Wi-Fi connection, and they want to verify the speed of the internet if they’re doing Zooms.

Another data point is that Mondays and Tuesday are the fastest-growing days of the week for travel. More people are treating ordinary weekends like long holiday weekends. This is also part of the flexibility afforded by remote work.

Finally, we’re seeing more people traveling nearby. We’ve seen a large increase in stays within 200 miles or less, which is basically a tank of gas. People are taking more extended staycations.

A home used to be a place for people to just live. But if it’s a place to live, or work, or be on vacation, then people can work from many homes if they want. Our relationship to our homes is changing.

Thompson: The sort of house that I would request for a work-slash-vacation is pretty different from, like, a small beach bungalow. I would want something a little bigger, something that felt a little more like a home and less like a tourist destination. Are you seeing changes in the sort of houses people are requesting?

Chesky: Price per night is going up because people are desiring larger spaces. Group sizes are increasing. One thing that’s happening is that as people seek longer stays to both work and relax, they want more space, more bedrooms, and a more equipped home. For those purposes, a studio apartment in Manhattan doesn’t look as good as a larger house in a smaller city or suburb. People care relatively more about space, not just place.

If you go to Airbnb now, we have a big button that says “I’m flexible” that’s been used 500 million times. This feature helps us point demand where we have supply. People used to choose the destination first. But now, for many, the home is the destination. People seem a bit more agnostic about where and when they’re traveling as long as they can find a big place with space to stay with family and friends.

Thompson: So bigger houses, longer stays, more deliberate Wi-Fi filtering, and more people turning normal weekends into unofficial holiday weekends. I can see how all of this points in a “workcation” direction. But I don’t want to overstate how many of these changes are specifically because of remote work. So much else is in flux. How sure are we that these aren’t just short-term trends caused by all the weirdness of the pandemic?

Chesky: I think remote work is a primary cause, but of course other things are happening. For example, we’ve seen a huge rise in people traveling to small towns and rural communities and national parks. I have many theories for this. When national borders are closed and museums are closed, you don’t go to Paris or other major cities. So people travel locally instead. Another theory is that as the need for business travel has been replaced or diminished, a lot of people who aren’t traveling for business still want to get out of the house. And so they discover or rediscover the town 200 miles away. They travel to stay around homes and friends, rather than checking off global landmarks.

Thompson: The other thing to be careful about when talking about white-collar-work trends is that only a minority of workers can work remotely, and a minority of those workers are still working remotely. So this trend might involve millions of people, but we’re talking about a minority of a minority.

Chesky: Obviously there are many, many jobs that aren’t affected by the rise of remote work. But for people within offices, those who work for tech companies or younger companies will embrace a more flexible policy. Within that group, you see that some companies, like Wall Street banks, are being less flexible, while others, like PricewaterhouseCoopers, Amazon, and Procter & Gamble, have announced permanent semiflexible policies. People without children are less tethered to their home than people with children. It’s easier to go somewhere for two weeks or a month if you don’t have kids. And it’s easier to turn a normal weekend into a three-day blended work-and-travel weekend if you don’t have to worry about their school.

Thompson: Which cities are benefiting from this trend on Airbnb?

Chesky: It’s fair to say that the team of winners is being democratized. There is a redistribution of travel destinations from big cities to smaller cities. The top destinations on Airbnb—the famous, high-density urban destinations like Vegas and Paris—used to be 11 percent of our nights booked in late 2019. Two years later, it’s 6 percent. People will still go to Paris and Vegas, but the genie is out of the bottle. There is a redistribution of travel away from a handful of hot spots toward everywhere.

Thompson: I have a pet theory that computers, knowledge work, and remote work are all producing a “Great Convergence” of work and life. Is this in line with what you’re observing in your business?

Chesky: We’re seeing work retreats and off-sites at Airbnbs, with teams gathering at Airbnbs, whereas before they might have sought out a typical off-site-event space with hotels.

Things tend to converge. The iPhone converged my calculator and the internet and the phone. And the home is becoming similarly multiuse. Travel, work, and living used to be compartmentalized. We traveled in one space; we worked in a different space; we lived in another space. It’s all coming together.

Thompson: I’m generally fascinated by the implications of remote work on cities, the economy, productivity, and technology. The second-order effects here could be extraordinary. Do you have any surprising second-order predictions about the future of work?

Chesky: I have a few predictions.

I think that travel will become a little less seasonal, a little more spread out throughout the year. Today, people travel around summer and the holidays. But one consequence of flexibility is that some people can book an Airbnb or hotel for a long off-season trip, when travel is cheaper. There’s a counterpoint to this, which is that business travel is diminishing. And business travel is somewhat off-season, since it happens throughout the year and is concentrated in the fall, when kids go back to school.

I also think about the larger effects. I’m 40 years old. The 26-year-old me started Airbnb in San Francisco because I had to do it in San Francisco. In 2007, venture capitalists needed you to come to their offices on Sand Hill Road [in Silicon Valley]. Now VCs do their meetings on Zoom. We plan to stay in San Francisco, but if I were starting Airbnb today, it’s possible I might have started it in many other cities.