America’s Real ‘Wokeness’ Divide

A new poll finds little difference between people with and without college degrees on questions about “wokeness.”

Overeducated people are ruining political discourse by embracing “woke” language. If you pay attention to modern fights about language and social justice, you’ve probably heard some version of this complaint. The Democratic patriarch James Carville has bemoaned the idea of “people in faculty lounges in fancy colleges” coming up with “a word like ‘Latinx’ that no one else uses.” John McWhorter, the linguist, Atlantic contributor, and author of Woke Racism, has asserted that “everybody is afraid of being called a racist on Twitter by articulate, over-educated people.” The Economist recently defined wokeness as “a loose constellation of ideas that is changing the way that mostly white, educated, left-leaning Americans view the world.” The thinking, or at least the impression, is that normal people who care about bread-and-butter economic issues go to college and pop out not caring about bread or butter, but instead worrying about gender pronouns and cultural appropriation. According to these sorts of arguments, people who never go to college stay reasonable, normal, or—depending on how you look at it—asleep.

But according to a recent Atlantic/Leger survey, no gap exists between people with college degrees and those without them on some of the hot topics most commonly associated with “wokeness.” Instead, neither group endorses the supposedly “woke” positions particularly strongly. Though the term originated in the Black community, woke now lacks a standard definition, and is sometimes used as a catchall label for a group of only loosely related ideas. People often use the term to describe neologisms that are more popular among progressives, such as pregnant people, as well as policy choices advocated for by some on the left, such as defunding the police. In our poll, we also included reverse-coded statements, meant to capture whether someone was the opposite of “woke,” by asking about common right-wing shibboleths such as political correctness, “cancel culture,” and critical race theory.

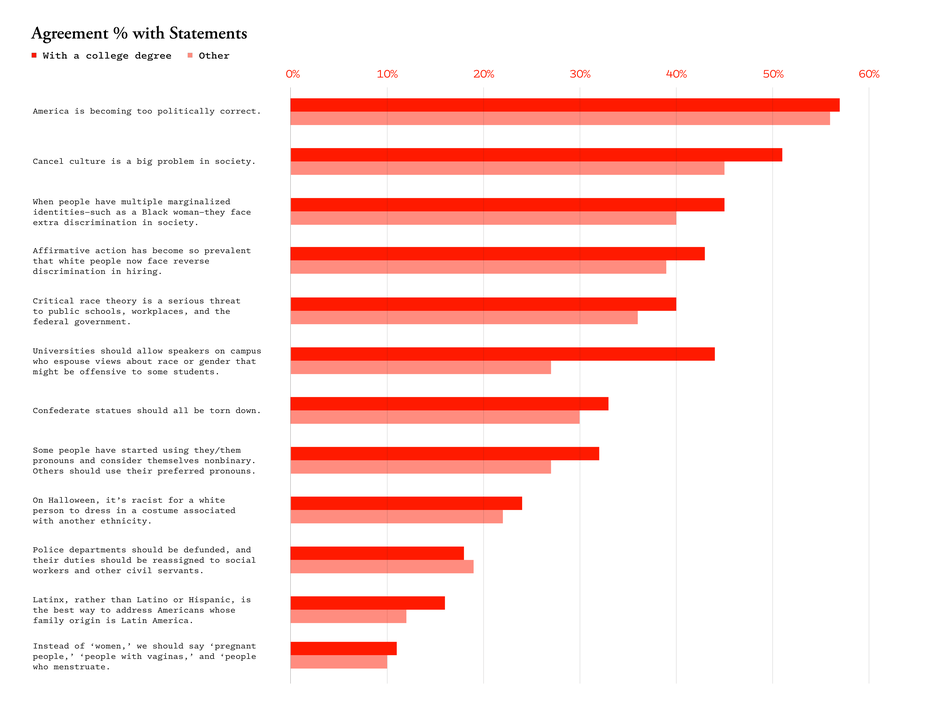

For the poll, Leger surveyed a representative sample of 1,002 American adults from October 22 to October 24. We asked for respondents’ agreements with various statements, shown in the chart below, that are often invoked by conservatives and moderates as being associated with people who are “woke.” The results showed that there was no significant difference between people with college degrees and those without them on the question of whether America is becoming too politically correct (slight majorities of both groups agreed somewhat or strongly). The same was true for believing “cancel culture is a big problem in society”—51 percent of degree holders agreed, as did 45 percent of those without degrees.

There was also no difference on questions pertaining to support for defunding the police; a preference for saying “pregnant people” instead of “pregnant women” or “Latinx” rather than “Latino or Hispanic”; for using gender-neutral “they/them” pronouns upon a person’s request; or agreeing that it’s racist to wear a Halloween costume associated with a different race or ethnicity. Less than 30 percent of respondents agreed with any of those, and it didn’t matter whether they had a college degree or not—at most, the college-educated were more likely to endorse these views by a few percentage points.

The only question on which the poll indicated a significant difference by education level was whether universities should allow speakers on campus who espouse views about race or gender that might be offensive to some students. But in that case, people who had a college degree were more likely to agree that the speakers should be allowed—44 percent, compared with 27 percent among those without a degree. When the results were cross-tabulated by race and education level, two more differences emerged: College-educated white respondents were slightly more likely than white respondents without a degree to say that Confederate statues should be torn down (31 percent compared with 24 percent), and that people who have multiple marginalized identities face extra discrimination in society (43 percent for white college graduates, compared with 35 percent for white nongraduates.)

To some researchers and Democratic pollsters, these results underscore how the college-noncollege divide in politics has been overstated. “Education polarization—this notion that that is the most important or most determinative variable that drives political behavior—is not true,” says Anat Shenker-Osorio, the head of the progressive firm ASO Communications. “It is handy to pretend that is the most useful variable, because it enables an argument wherein the way the Democratic Party has lost its way is by over-indexing to purportedly woker-than-thou white people on the coast who have lots of formal education.”

The results also serve as a reminder of the typical college experience—not just now, but historically. Of the 36 percent of Americans over 25 who have at least a bachelor’s degree, the majority did not attend an elite or even very selective school. The University of Central Florida has more undergraduates than the entire Ivy League. A lot of American 45-year-olds attended a state school, run a small business, and watch Fox News. Those people are college graduates too.

What’s more, our “noncollege” group includes people who are still in college—that is, it includes the supposed social-justice warriors who are canceling their own professors. About 6 percent of American adults are currently undergraduates. Indeed, the biggest differences in attitudes toward these questions appear to break along age lines: People over 50 were significantly more likely than those ages 18 to 29 to agree that “America is becoming too politically correct”; that “critical race theory is a serious threat to public schools, workplaces, and the federal government”; or that “affirmative action has become so prevalent that white people now face reverse discrimination in hiring.” Fully 68 percent of people over 65 said America is too politically correct. Meanwhile, the greatest support for the tearing down of Confederate statues, for the use of gender-neutral pronouns, for defunding the police, and for saying “Latinx” or “pregnant people” was among respondents under 40—yet these views still represented a minority of overall respondents. “The more ‘woke’ attitudes, respecting pronouns—those are really things being driven by a younger generation,” says Natalie Jackson, the director of research at the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI).

It’s also possible that young people who aren’t yet in college, or who will never go to college, are becoming more progressive. “Students were showing up to campus with these ideas,” says Greg Lukianoff, the president of the free-speech group Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, who has also contributed to The Atlantic. He points both to what he sees as more “ideological” programming in K–12 schools and the rise of platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. “Social media also played a big role in that social-justice-style argumentation really took off, because it’s pretty ideal for short-form ‘mic drop’–style argumentation.”

Whether young people will age out of their liberalism—as some liberals do—is unclear. But language is constantly evolving, and once terms such as pregnant people become the norm among younger generations, they tend to persist. Referring to women as “Ms.,” rather than by the marital-status markers Miss and Mrs., was controversial until it became widely accepted.

Though college graduates tend to be more reliable liberals than Americans without a degree, some past surveys have similarly found small, if any, differences between those who graduated from college and those who didn’t on various measures of social-justice affinity. In a 2017 PRRI poll, white, college-educated Americans expressed less concern about the lack of equal opportunity in America than those without a college degree (56 percent versus 63 percent, respectively). And about two-thirds of white men both with and without a college degree told NPR in 2018 that the country was becoming too politically correct.

Rather than education, several Democratic strategists told me, the real political divides among white voters are whether they live in rural or urban areas, and whether they consider themselves evangelical Christians. And, perhaps expectedly, even bigger cleavages emerged in our poll when participants were asked whom they voted for in the last presidential election: On every question, Donald Trump voters overwhelmingly disagreed with social-justice views. Nearly 70 percent of them thought “cancel culture is a big problem in society,” compared with 31 percent of Joe Biden voters. Just 21 percent of Trump voters think “people with multiple marginalized identities face extra discrimination in society”—a question meant to gauge people’s endorsement of intersectionality—compared with 63 percent of Biden voters.

Many of the progressive ideas were more popular among people of color than among white people. Only 37 percent of nonwhite respondents thought America was too politically correct, for instance, compared with 62 percent of white respondents. Among people of color, 45 percent agreed that Confederate statues should be torn down, but just 27 percent of white people did. However, equal numbers of white and nonwhite respondents endorsed gender-neutral pronouns (29 percent). Other polls have found that a majority of Black Americans support defunding the police, and that white people are more likely than Black people to think it’s important for police to be armed and well funded.

The poll showed that, overall, not very many people support the emerging language around identity. Only 10 percent of respondents agreed that we should say “pregnant people,” and just 14 percent think people should say “Latinx.” This suggests that not many people have embraced this style of speaking, but also that the “threat of wokeness” might be overstated, given that relatively few people appear to actually be “woke.”

Several people I interviewed said this poll’s structure and phrasing might be dragging down the popularity of some of these statements. For example, the poll did not explain why someone might say “pregnant people” instead of “pregnant women”—it’s to acknowledge that transgender men and nonbinary people can also get pregnant. With the added context, the phrase might have registered as more popular. And because we asked so many questions on the same theme, respondents might have been subject to priming effects—getting worked up about political correctness and reacting more strongly to all the statements than they otherwise would have. Significant numbers of people answered “No opinion” or “I don’t know enough about this to respond” to some of the questions, including the ones about Latinx, they/them pronouns, campus speakers, and critical race theory. That suggests a bit of “general confusion on what some of these things mean, and why we would do any of it,” says Jackson, of PRRI.

Still, other polls have also found that a slight majority of all Americans feel that people are now too easily offended by what others say. Ideas such as reducing police funding don’t poll well among all Americans, either. To anyone who is jarred by results like these after spending a day on Twitter, the explanation is partly just that “Twitter is very, very much not real life,” Jackson says. Only about 20 percent of Americans use Twitter, and 80 percent of all tweets come from just 10 percent of tweeters. Twitter users are also younger and more liberal than U.S. adults overall—so much so that the Washington Post columnist Perry Bacon Jr. recently called Twitter “the media platform for the most progressive Democrats.” That helps explain why a concept like “defund the police” can catch on there but sputter offline.

No one should base policy, strategy, or their behavior on just one poll. Simply because an idea doesn’t poll well doesn’t mean it should be scrapped: One role of policy is to protect minorities from the opinions of majorities. Americans can be convinced to change their views: Marriage equality and Black Lives Matter are two recent examples of liberal ideas that started out unpopular but eventually achieved widespread support. And though some of the phrases we asked about are associated with liberal activists, few, if any, Democratic candidates have actually run on a “Defund the police” or “Bring on the critical race theory” platform.

Though the flashiest elements of “wokeness” might not seem very popular, the good news is that Americans are embracing racial justice more and more. “Americans’ broader views of race, racism, immigration, and other topics have become more liberal,” John Sides, a political scientist at Vanderbilt University, told me via email. “Relative to ten years ago, more Americans think that immigration is good. More Americans think that racial inequality stems from structural factors like discrimination, not from Black Americans’ lack of effort.” That suggests many Americans generally endorse the idea of racial equality, even if they don’t always like the language used to describe it.