The Serendipity of ‘Let’s Go, Brandon’

The anti-Biden meme is meaner than your grandfather’s shoot or heck. It also offers a fascinating view of how language changes.

I know how I am supposed to feel about “Let’s go, Brandon”: Mocking the president this way is uncivil, a sign of the collapse of once-routine public courtesy, etc., etc. How I really feel about it, though, is that it’s fascinatingly serendipitous, seriously funny, and intriguingly fecund. From that one meme, others are being born.

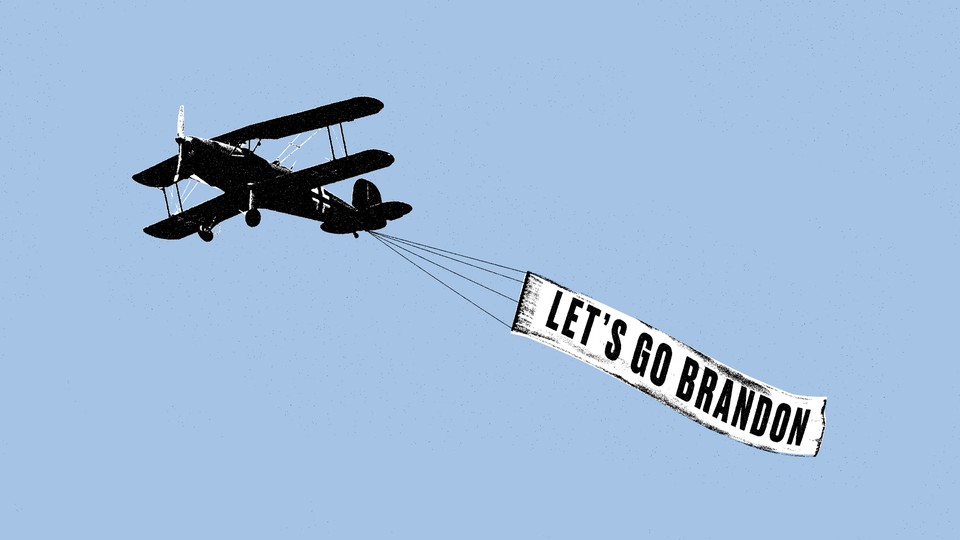

Last month, an NBC reporter interviewing the victorious NASCAR driver Brandon Brown heard fans in the stands chanting “Fuck Joe Biden” in lustily contemptuous unison. The reporter insisted to viewers that the fans were in fact chanting “Let’s go, Brandon.” This improvisation made no sense. Brown had won, so why would anyone cheer him on by saying “Let’s go!” after he’d just accomplished quite a bit of going? Since then, Biden’s detractors have adopted “Let’s go, Brandon” as a kind of in-group salute—a coded way of saying, well, the other thing. The meme has found its way onto T-shirts, masks, signs at other sporting events, the House floor, and (reportedly) airplane intercoms, and was parodied this weekend in an online video from Saturday Night Live.

Interestingly, despite its very American origins, the catchphrase is rather South African. Stay with me: In traditional societies there, such as in Zulu and Xhosa communities, a woman marrying into a family shows respect by refraining from using any words that sound like her husband’s or in-laws’ names and subbing in other words. Imagine if someone married William Green, the son of Robert Green, and instead of saying, “She will not eat green yogurt,” had to say, “She refuses to eat grass-colored yo-mix”—because will and green are her husband’s names and the second half of yogurt sounds like the end of Robert. The practice is called hlonipha, and “Let’s go, Brandon” is a coy substitution of the same kind.

However, the anti-Biden euphemism is of a meaner tone. This is not your grandfather’s darn, heck, shoot, or fudge. Those are polite terms, expressed without the teeth-baring ardor of the words they stand in for, imaginable as things that characters played by Edie McClurg might say in ’80s movies such as Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. “Let’s go, Brandon” springs from the mangier, madder place of euphemisms such as snafu—which during World War II everyone in the American military knew was an acronym for “situation normal, all fucked up”—or right-wingers’ dismissal of conservatives who do not toe the party line as cuckservatives, rooted in the word cuckold.

Those who dislike seeing President Biden’s name used disparagingly should welcome the latest development: People on the left are declaring “Thank you, Brandon” in praise of the administration’s accomplishments thus far. We are witnessing the birth of a diagonal reference to Biden that signals a defense of him from the slurs of the right. Brandon could well take its place as one of those bemusingly opaque code names such as Yeezy for Kanye West or Boz for Charles Dickens—or as one of those pseudonyms that some members of Congress direct their staff to use for them when talking about work in social settings. (A friend of mine who worked on Capitol Hill in the late 1980s referred to her boss as “Bubo,” lest eavesdroppers in public spaces pick up insider gossip about congressional business.)

We might simply embrace that sentiments will differ about this Brandon person in exactly the same way as they do about, well, Biden. Calling him Brandon when dissing him could be seen as a kind of American hlonipha. And yet, in elite circles, one senses a bifurcation: Brandon is warm and wise when preceded by Thank you but an unacceptable epithet coming from Republicans.

Few of the commentators who decried the supposed vitriol and vulgarity of “Let’s go, Brandon” appear to mind Democrats’ attempt to repurpose the race-car driver’s name. The tacit idea would seem to be that when the left throws shade, it counts as speaking truth to power and is thus okay. Until the late ’80s, some people on the left used politically correct unironically to suggest, without saying so, that right-wing views are inherently and incontestably wrong. The designation of conservatives outside Democratic enclaves as “deplorables” didn’t come from the right, either.

Overall, “Let’s go, Brandon” is simply fascinating. A time traveler from 2019 would have been mystified at the bewigged people going as Karen this Halloween (I saw two) as well as those in mustaches going as Ted Lasso (of which I also saw two). In the same way, think how utterly opaque “Let’s go, Brandon” would be to a time traveler from just Labor Day. The meme is a wild, woolly kink in the intersection of language, politics, wit, and creativity, and is a prime example of why language change is a spectator sport.