The Self-Help That No One Needs Right Now

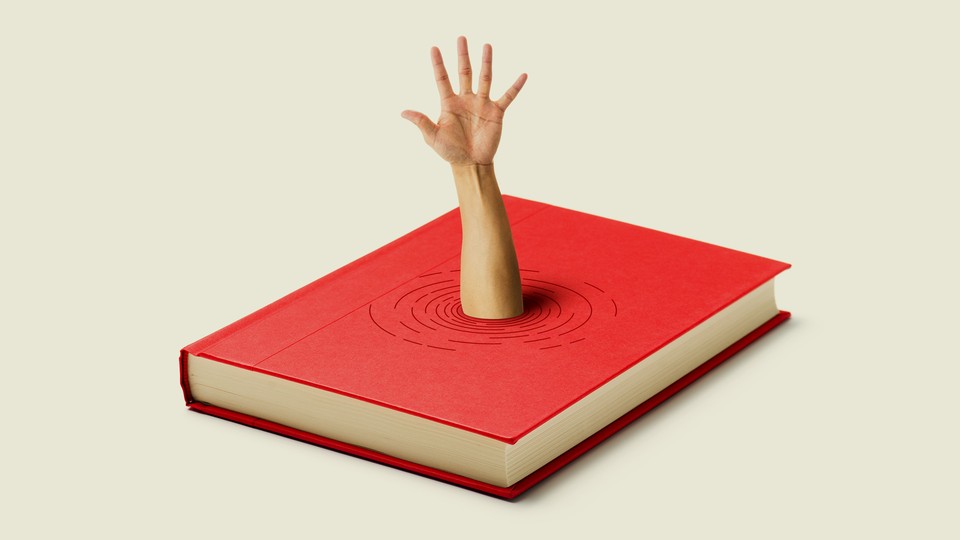

The pandemic has boosted interest in trauma books full of advice that isn’t particularly relevant to what most Americans are going through.

Nothing about The Body Keeps the Score screams “best seller.” Written by the psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk, the book is a graphic account of his decades-long career treating survivors of traumatic experiences such as rape, incest, and war. Page after page, readers are asked to wrestle with van der Kolk’s theory that trauma can sever the connection between the mind, which wants to forget what happened, and the body, which can’t. The book isn’t academic, exactly, but it’s dense and difficult material written with psychology students in mind. Here’s one line: “The elementary self system in the brainstem and limbic system is massively activated when people are faced with the threat of annihilation, which results in an overwhelming sense of fear and terror accompanied by intense physiological arousal.”

And yet, since its debut in 2014, The Body Keeps the Score has spent 150 weeks—nearly three years—and counting at the top of the New York Times best-seller list and has sold almost 2 million copies globally. During the pandemic, it seems more in demand than ever: This year, van der Kolk has appeared as a guest on The Ezra Klein Show, been profiled in The Guardian, and watched his book become a meme. (“Kindly asking my body to stop keeping the score,” goes one viral tweet.)

After all the anxiety and social isolation of pandemic life, and now the lingering uncertainty about what comes next, many people are turning to a growing genre of trauma self-help books for relief. The Body Keeps the Score is now joined on the best-seller list by What Happened to You?, a compilation of letters and dialogue between Oprah Winfrey and the psychiatrist Bruce D. Perry. Barnes & Noble, meanwhile, sells about 1,350 other books under the “Anxiety, Stress & Trauma-Related Disorders” tab, including clinical workbooks and mainstream releases. Sometimes, new installments in the genre seem to position themselves as a cheat code to a better life: Fill out the test at the back of the book; try these exercises; narrativize your life. One blurb I read, on the cover of James S. Gordon’s Transforming Trauma, basically said as much: “This book could give you back your life in unimaginable ways, whether you think of yourself as a trauma victim or not.”

“You can kind of understand why the sales of these books are going up in this stressful, pressurized situation,” Edgar Jones, a historian of medicine and psychiatry at King’s College London, told me. In a moment of personal and collective crisis, the siren song of a self-help book is strong.

There’s just one problem. In spite of their popularity, trauma books may not be all that helpful for the type of suffering that most people are experiencing right now. “The word trauma is very popular these days,” van der Kolk told me. It’s also uselessly vague—a swirl of psychiatric diagnoses, folk wisdom, and popular misconceptions. The pandemic has led to very real suffering, but while these books have one idea of trauma in mind, most readers may have another.

The Greek term for “wound,” trauma was initially used to refer to physical wounds. Although today’s best sellers seem to provide all the answers, psychiatrists began to widely embrace the notion of purely psychological trauma only around World War I. But the disorder has evolved since the days of shell shock. The current diagnosis of PTSD dates back to only 1980, applied to the flashbacks experienced by some soldiers who had served in the Vietnam War.

In the decades since, trauma has come to signify a range of injuries so broad that the term verges on meaninglessness. The American Psychological Association, for example, describes trauma as “an emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, rape or natural disaster”—like, but not only. “Like weeds that spread through a space and invasively take over semantic territory from others,” trauma can be used to describe any misfortune, big or small, Nicholas Haslam, a psychology professor at the University of Melbourne, told me. That concept creep is evident on TikTok, where creators use “trauma response” to explain away all kinds of behavior, including doomscrolling and perfectionist tendencies.

In the pandemic, trauma has become a catchall in the U.S. for many varied, and even competing, realities. Some people certainly are experiencing PTSD, especially health-care workers who have dealt with the carnage firsthand. For most people, however, a better description of the past 19 months might be “chronic stressor,” or even “extreme adversity,” experts told me—in other words, a source of immense distress, but not necessarily with severe long-term consequences. The whole of human suffering is a lot of ground for one word to cover, and for trauma best sellers to heal.

Today, a comprehensive shelf of trauma self-help includes the biophysicist Peter Levine’s Waking the Tiger, which argues that a lack of trauma in wild animals can offer insight into how humans might overcome their seemingly unique susceptibility to it; The Deepest Well, by the surgeon general of California, Nadine Burke Harris, who uses personal experience to draw a direct line from childhood stress to a host of physical and social ills; and It Didn’t Start With You, in which the author, Mark Wolynn, makes the controversial claim that trauma can be inherited from distant ancestors.

These books tend to follow a reliable arc, using the stories of trauma survivors to advance a central thesis, and then concluding with a few chapters of actionable advice for individual readers. In The Body Keeps the Score, van der Kolk writes about people he refers to as Sherry, a woman who was neglected in childhood and kidnapped and repeatedly raped for five days in college, and Tom, a heavy drinker whose goal was to become “a living memorial” to his friends who had died in Vietnam. For patients like these, van der Kolk eventually turned to yoga, massage therapy, and an intervention called eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing, or EMDR, which specifically treats the traumatic memories that pull people with PTSD back into the past.

Those experiences are remarkably different from what most Americans have endured in the pandemic. Although almost everyone has struggled with the risk of contracting a deadly virus and the resulting isolation and potential loneliness, a remote worker’s depressive episode, or an unemployed restaurant worker’s inability to pay their bills, has little in common with stories like Tom’s and Sherry’s. They are no less important—no less deserving of attention—but we need better words to describe them, and other remedies to treat them.

Even van der Kolk himself is wary of some of the ways in which trauma is used today. When I asked him whether he thinks The Body Keeps the Score is useful for all the readers turning to it during the pandemic, he objected to the premise of my question: The readers he hears from most, he said, are those who grew up in abusive households, not those who feel traumatized by COVID-19. “When people say the pandemic has been a collective trauma,” van der Kolk said, “I say, absolutely not.”

Still, the trauma books keep selling. Some lessons they contain are universally applicable, if a little trite. In What Happened to You? Oprah and her co-author dedicate a chapter to their spin on the idea of “post-traumatic growth,” a concept popular again in the pandemic, as people search for a silver lining to what they’ve been through. But sometimes, there is no wisdom to glean or personal growth to uncover—what happened happened, and people move forward anyway. Other recommendations, as with van der Kolk’s emphasis on EMDR, are specific to people with more typical symptoms of PTSD. Most people just don’t need those kinds of interventions, says George Bonanno, a clinical-psychology professor at Columbia University and the author of The End of Trauma. In the aftermath of disasters such as 9/11, Bonanno has found remarkable resilience, despite the odds. Yet people “don’t seem to want to let go of the idea that everybody’s traumatized,” he told me.

Surely some people find solace in these books, whatever their reason for reading. And not all trauma books have these pitfalls. In My Grandmother’s Hands, the therapist Resmaa Menakem examines the physical and emotional toll of racism and white supremacy, and his advice charts a different course. When people feel they have experienced a collective trauma, Menakem writes, “our approaches for mending must be collective and communal as well.” When it comes to the challenges Americans now face—as varied as responding to the pandemic and acting on climate change—that’s advice worth taking.

Ultimately, talking about trauma isn’t just a semantic matter. “Having a tight, limited idea of what mental illness looks like is a recipe for stigma; it’s a recipe for not seeking help for oneself [and for] not offering help to others,” Haslam said. The desire to validate other people’s suffering “is a good corrective,” he added. “It just happens to be a pretty blunt object in this concept of trauma.” And that is the major lesson you’ll learn if you can make it to the end of this grueling syllabus: We still have so much to understand about trauma. If we want a shot at addressing the real consequences of the pandemic, we will need not only more research but a new language—one that expresses terrible experiences that aren’t strictly traumatic and leads to solutions that are bigger than any one of us in isolation. Until then, trauma books will just keep flying off the shelves.