The Democrats’ Last Best Shot to Kill the Filibuster

An antiquated rule keeps standing in the way of Joe Biden’s agenda.

From multiple directions, the crisis over the filibuster is peaking for Democrats.

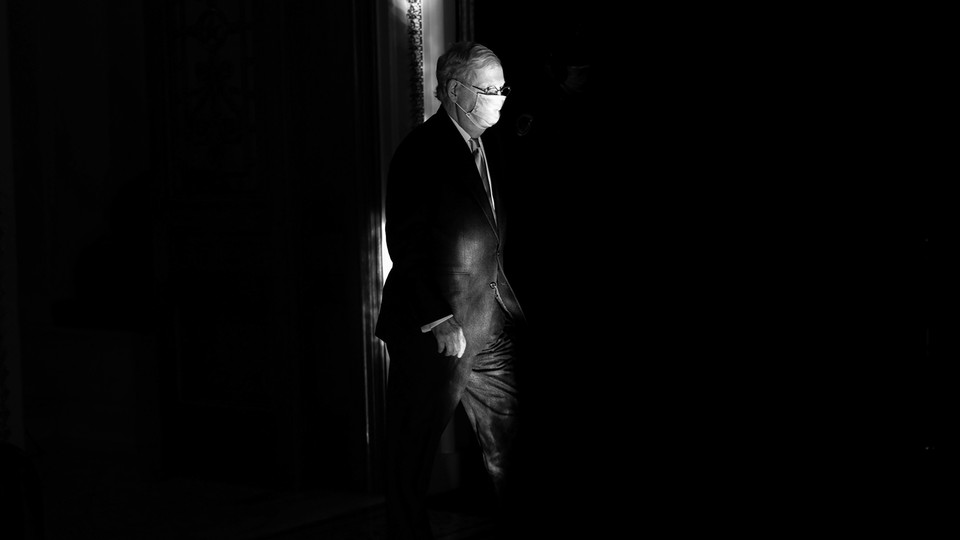

In just the past week, the casualty count of Democratic priorities doomed by the filibuster has mounted; both police and immigration reform now appear to be blocked in the Senate, and legislation codifying abortion rights faces equally dim prospects. Simultaneously, the party has tied itself in knots attempting to squeeze its economic agenda into a single, sprawling “reconciliation” bill, because that process offers the only protection against a GOP filibuster. Meanwhile, legislation establishing a new federal floor for voting rights, the party’s top priority after the reconciliation bill, remains stalled in the Senate under threat of another GOP filibuster. And then, this week, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell raised the temperature even higher by leading a Republican filibuster that has blocked Democratic efforts to raise the nation’s debt ceiling.

“On voting rights, budget and reconciliation, potential economic calamity [over the debt ceiling]—this is a very clarifying few weeks,” says Eli Zupnick, a spokesperson for Fix Our Senate, a liberal group advocating for ending the filibuster. “Our hope is this will culminate in Democrats finally realizing they cannot keep preserving this weapon that McConnell can use to derail their agenda and hurt President Biden’s ability to govern.”

Reform advocates don’t expect Democrats to resolve the latest standoff by exempting the debt ceiling from the filibuster—most bet that the party will eventually turn to the special budget-reconciliation process to pass the increase. But they do hope the Republican willingness to court default and financial chaos by filibustering the debt-ceiling increase will pressure Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona to reconsider their blanket defense of the rule.

“The debt ceiling is an exacerbating dynamic putting salt in the wound in a way that might expedite filibuster reform on other fronts, like voting rights,” says Adam Green, a co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, a liberal advocacy group. Like other filibuster opponents, he says the stalemate over the debt ceiling should send yet “one more signal to Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema that these [Republicans] are not rational or good-faith actors.”

McConnell’s latest maneuver on the debt ceiling may have inadvertently made the strongest case yet for changing the filibuster.

As he’s done before on Supreme Court confirmations, McConnell recently conjured a self-serving new “rule.” The Senate Republican leader declared that the majority party alone should bear the burden of passing the politically fraught debt-ceiling legislation. As he explained it to Punchbowl News, “The country must never default. The debt ceiling will need to be raised. But who does that depends on who the American people elect.”

By itself, that was not a remarkable assertion. Senate Democrats also provided almost no votes to raise the debt ceiling while Republicans controlled the White House and both legislative chambers during the middle years of George W. Bush’s presidency.

The catch is that while McConnell contended that the majority party alone must raise the debt ceiling as its “sole responsibility,” he also insisted that the minority party should maintain a veto on whether it does so through the Senate filibuster. On Monday, he was as good as his word, leading a GOP filibuster of the Democratic legislation to increase the ceiling and to provide the funding to keep the federal government open past this week. That represented a new escalation of the partisan wars: Although Senate Democrats generally didn’t vote to raise the debt ceiling under Bush, they didn’t filibuster to block the GOP majority from doing so.

McConnell’s “Heads I win, tails you lose” formulation on the debt-ceiling issue captures the structural change in Congress’s operation that has rendered the filibuster even more pernicious and illogical than it was in earlier generations.

His assertion that the majority party alone should raise the debt ceiling actually demonstrates how Capitol Hill works in the modern era: Congress now functions essentially as a quasi-parliamentary institution, and it has an enormous level of party-line voting and very little cooperation across partisan lines. But McConnell’s contention that the minority party should retain a veto through the 60-vote threshold underscores how the filibuster has created a parliamentary system without majority rule. That’s a contradiction in terms.

The point of a parliamentary system is that the majority rules. It assumes that legislators from the parties not in power will oppose the governing party’s program but allows the ruling party to advance its agenda anyway through a simple majority vote. The United States, as McConnell’s threat shows, upholds the first part of that equation, but not the second. Because of the parliamentary level of party discipline that now exists, presidents can’t realistically expect much support from the opposition party on their major priorities; but because of the filibuster, they can’t pass those priorities without support from the other party (except for isolated exceptions such as judicial and executive-branch appointments and the budget-related measures that are eligible for the reconciliation process, or the rare case when either party controls at least 60 Senate seats).

“It’s absolutely crazy to say that on the one hand, it’s the majority’s responsibility to govern, and on the other hand, the majority shouldn’t be able to govern without our participation,” says Lee Drutman, a senior fellow in the political-reform program at New America, a center-left think tank. “It’s either got to be one or the other. But I guess, on Tuesday, it’s the majority party’s responsibility to govern, and then on Wednesday, it’s the majority party’s responsibility to make sure they have consent of the minority party.”

Combining the filibuster with a parliamentary-type system of party discipline “is totally wacko by any modern standards of democracy,” Drutman told me. “Look around the world. No other country has a 60-vote threshold for ordinary legislation, nor have there been at least for a century, if not longer. If it was such a good idea, why are we the only democracy in the world that has it?”

By blocking the debt-ceiling legislation—which would trigger a catastrophic U.S. default on its debt—McConnell and Senate Republicans are, in effect, holding a gun not only to the head of Democrats but also to the global economy. But Democrats could end the madness at any time. All 50 Senate Democrats, joined by Vice President Kamala Harris, could neutralize McConnell’s threat by voting to end the filibuster, or even just to exempt from it legislation raising the debt ceiling. But strikingly, amid all the keening about the cataclysms that default could trigger, neither Senate Democrats nor the White House have even floated that possibility, a measure of their pessimism about moving Manchin and Sinema to that position. Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer on Tuesday instead asked Republicans to voluntarily withdraw their filibuster and allow Democrats to raise the debt ceiling by majority vote—a request McConnell immediately, and predictably, rejected.

Even before Washington potentially tumbles into a government shutdown, a default on the federal debt, or both, the filibuster has imposed a rising toll on the Democratic agenda. Police reform hit the wall last week when negotiations between Republican and Democratic senators collapsed, dooming any chance to reach 60 votes. Immigration reform was derailed when the Senate parliamentarian ruled it ineligible for inclusion in the reconciliation legislation. Bills creating a universal-background-check system for gun sales and establishing nationwide protections against discrimination for the LGBTQ community, after earlier passing the House, have both disappeared from view, also without prospect of attracting the 10 Republicans required to break a filibuster. The legislation to establish a new nationwide floor for voting rights remains in limbo, leaving Manchin to ostensibly seek Republican support for a compromise measure that Democrats renegotiated around principles he put forward. But his best potential GOP targets, Senators Lisa Murkowski and Susan Collins, have already dismissed the new proposal, quickly extinguishing his chances of attracting the 10 votes he would need to break a filibuster. Republicans are even less likely to support the sweeping Protecting Our Democracy Act that House Democrats introduced with great fanfare last week to respond to the many ways in which former President Donald Trump abused his authority over the executive branch.

Though the differences between progressives and moderates have dominated the struggle over Biden’s economic agenda consuming Washington this week, the filibuster has heightened the pressures there as well. One reason the negotiations have been so difficult is that Democrats are trying to shoehorn so many consequential policies into a single reconciliation bill—for universal pre-K, free community college, green energy, a major expansion of Medicare—because that special process provides their one chance to shelter these priorities from Republican filibusters. As Dan Pfeiffer, the White House communications director for President Barack Obama, wrote last week, “Any of these on their own would be hard. Doing them all at once is nearly impossible. But this is the only option because Senate Democrats won’t fix the filibuster, and Republicans will not lift a finger to help.”

The filibuster isn’t the sole cause of the Democrats’ difficulties in this grueling period. They are pursuing big policy changes on slender legislative majorities. It’s not certain that some of the initiatives the House has passed (certainly regarding abortion rights and raising the minimum wage, maybe police reform) could attract 50 Senate votes even if the filibuster was eliminated. And raising enough tax revenue to create (or expand) as many government programs as Democrats are seeking to would be tough under any circumstances.

But the Senate filibuster looms as the biggest obstacle to the broadest range of Democratic priorities. Even if the party ultimately coalesces behind a robust reconciliation bill, failing to confront the filibuster guarantees that it will head into the 2022 midterm elections without the legislative progress Biden promised on issues as central to core Democratic constituencies as immigration, police reform, voting rights, gun control, raising the minimum wage, and safeguarding abortion and LGBTQ rights. That prospect is drawing stark warnings from groups that helped mobilize the massive turnout in 2020 that gave Democrats unified control of Washington in the first place.

In 2022 and 2024, “is it going to be our job to go out and to explain to people, ‘Hey, we know you turned out in 2020 in the midst of a global pandemic … You put your health on the line … You overcame all sorts of voter-suppression tactics, and now let me tell you why none of those things actually happened that you thought you were promised: It’s this thing called the filibuster,’” Rashad Robinson, the president of the racial-equity advocacy group Color of Change, told me on a panel at The Atlantic Festival on Tuesday. “Democrats are making a huge miscalculation if they think that folks are going to continue to put rocks on their backs and climb uphill to battle all the suppression attempts if the Democrats are not willing to do the work to undo … Jim Crow rules that time and time again have been used to stall progress.”

Filibuster critics have made some progress this year. Adam Green believes that all other Democratic senators beyond Manchin and Sinema would now accept at least some changes to the rule. “Many of the [senators] who just two years ago would have been seen as far-fetched allies are now outwardly saying we need to reform the filibuster,” he told me. Whereas up to a dozen might have resisted change before this year, he said, opposition “is down to the final two.”

Manchin and Sinema might, in fact, be among the final Democratic senators ever who oppose ending the filibuster: A recent HuffPost survey of 2022 party Senate candidates found near-total support for undoing it, and even moderates such as Representative Conor Lamb of Pennsylvania (who’s seeking the party’s Senate nomination there) expressed opposition. And although Biden has been, at best, unenthusiastic about the change, it’s difficult to imagine anyone winning a future Democratic presidential nomination without explicitly committing to ending or retrenching the filibuster.

Yet all of that will be cold comfort to Democratic activists if party leaders can’t persuade Manchin and Sinema to renounce the filibuster in this Congress—if only to create a carve-out from it for the federal voting-rights legislation. Democrats now have unified control of government but remain stymied on many issues by their refusal to confront the disaster of the filibuster. By the time a new generation of Democrats summons the will and consensus to reconsider the rule, the party could lose its control of government. Either scenario leaves them unable to pass the party priorities. Once that window shuts, it might not reopen for some time. If Democrats lose either the House or the Senate in 2022, it could take many years before they again control both chambers and the White House—especially if they fail to pass voting-rights legislation counteracting the laws and congressional gerrymanders that red states are passing to tilt the electoral playing field toward the GOP.

Given the parliamentary dynamics of the modern Congress on vivid display this fall, a Senate vote to weaken or eliminate the filibuster seems almost inevitable in the next few years: It’s an anachronism in a system defined by greater cohesion within the parties and more conflict between them. The real question may be whether Democrats dismantle it themselves now, or watch as Republicans do it the next time they hold unified control of Congress and the White House.