A Film About the Impossible Job of Valuating Lives

Worth, a Netflix movie about the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, reminds us that tragedies can’t be neatly quantified.

What is the value of a human life? This is the question with which the lawyer Kenneth Feinberg (played by Michael Keaton) opens the new Netflix film Worth, stressing to his students that he’s not posing it as a philosophical query. He is a high-powered mediator who assesses damages in cases involving unexpected, large-scale death—such as lawsuits involving Agent Orange or, in the case of this film, the September 11 attacks. Feinberg’s job is to calculate the monetary value of lives lost—to turn names into dollars and cents—in a chilling role befitting our capitalist society.

As Worth begins, Feinberg leads his law students through a mock case in which someone dies in a farming accident and his family sues for damages. Abstract numbers are bandied about until the class agrees that $2.7 million sounds right; Feinberg’s lesson is that putting a price tag on a soul can be that easy, and that arbitrary. Sara Colangelo’s film, an adaptation of the real-life Feinberg’s memoir, is about the attorney being handed the same challenge on a staggering level: running the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, which paid out damages to thousands of families still recovering from the attacks.

Colangelo’s movie, written by Max Borenstein, was released yesterday, just a week before the 20th anniversary of 9/11. That timing wasn’t always planned—Worth debuted at the Sundance Film Festival back in January 2020. But it means the movie functions as a timely tribute of sorts: a consideration of how bureaucracy can be both a calming force and an infuriating obstacle following incomprehensible trauma. In Worth, Feinberg is appointed to ease families’ suffering. At the same time, he’s expected to be a bulwark against those same families’ demands. Eventually, he has to understand that a business-as-usual approach simply can’t contain a tragedy of this size.

The September 11th Victim Compensation Fund was created not merely out of a sense of duty, but also out of fear within the government that people would bring legal action against airlines for huge damages, crippling a major industry at a tenuous moment. In Worth, Feinberg’s job is to sell thousands of grieving families on financial settlements in return for their declining to sue, and he’s given broad power to decide who gets what from a multibillion-dollar fund. Keaton plays Feinberg as an avuncular, no-nonsense presence, convinced that he can hammer a system of fairness out of calamity, even though the 9/11 victims encompassed a wide range of ages, salaries, and occupations.

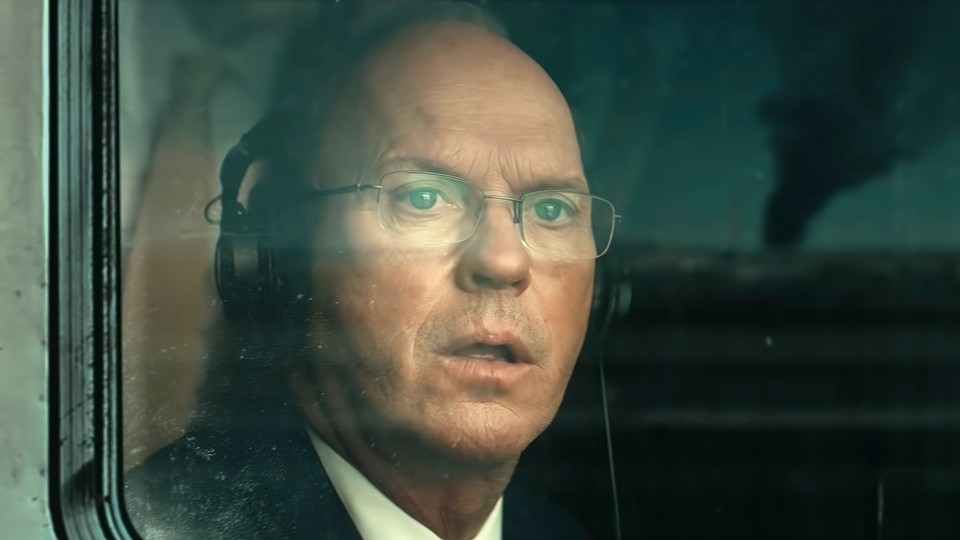

Colangelo sets almost the entire first half of Worth in offices and boardrooms—the more anonymous, the better. The only glimpse audiences see of the attacks themselves is in the reflection of Feinberg’s commuter-train window, as he and other passengers stare at a pillar of smoke off in the distance; everything else is filtered through news broadcasts, audio recordings, and other media. The antiseptic distance is intentional. Though Worth’s Feinberg is not emotionless, he’s also erecting familiar force fields, trying to divorce his feelings from the strange task of devising mathematical formulas to estimate what the dead might have been able to earn had their lives not been cut short.

Keaton is in a phase of his career where he excels at playing pillars of credibility—white-collar guys with a blue-collar evenhandedness. His work as Feinberg is reminiscent of his terrific performance as the dogged newsman Robby Robinson in Spotlight, or as former Attorney General Ramsey Clark in The Trial of the Chicago 7. He never raises his voice, never patronizes anyone, and rarely even flashes the toothy grin that made him a movie star back in the days of Batman and Beetlejuice. His performance crucially retains the audience’s sympathies even as Feinberg is a figure of frustration to everyone around him, upsetting both co-workers and victims’ families who care about compassion, not just compensation.

Charles Wolf (Stanley Tucci), a dogged advocate whose wife died in the attacks, eventually becomes the voice of reason for Feinberg, helping him understand that he has to step out of the boardroom and meet people face-to-face. Tucci and Keaton had similarly powerful chemistry in Spotlight (another gripping film largely staged in dingy offices), and the arc of their relationship in Worth, from adversaries to allies, undergirds a movie that might have otherwise felt like a series of endless meetings. A separate plot about the grieving wife of a firefighter (Laura Benanti) is too overwrought for the film’s muted tone, since she seems like a fictionalized stand-in for a whole group of people, whereas Worth’s key message is about coming to understand each individual loss.

Colangelo communicates the magnitude of the devastation not through visceral imagery and flashbacks, but through simple remembrance, with family members telling specific stories of the people they lost so Feinberg can understand that they’re more than numbers to be plugged into an algorithm. Watching the bureaucracy shift from a source of frustration to comfort gives the film its arresting tension. Nearly two decades after 9/11, Feinberg’s realization is also the audience’s reminder: The event was a shock to the United States that even billions of government dollars couldn’t reverse, and only by looking closely and empathetically at its human cost can we really understand what was lost.