The Neighborhood Fighting Not to Be Forgotten

One hundred years after the Tulsa Race Massacre, community members still can’t get the federal government to recognize Greenwood’s significance.

When Brenda Nails-Alford received the letter informing her that her ancestors were survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, she had to reread it five times. The massacre was a two-day onslaught of racial violence that is believed to have killed hundreds of people and laid waste to the prosperous Black neighborhood of Greenwood—which included a business district known as “Black Wall Street”—in Tulsa, Nails-Alford’s hometown. She had never heard of it.

In 2003, a legal team sued the city of Tulsa, the Tulsa Police Department, and the state of Oklahoma on behalf of more than 300 of the massacre’s survivors and survivors’ descendants. After their letter reached Nails-Alford, she drove to Greenwood and walked up and down the streets, just like she had as a kid. Her memories suddenly felt haunted.

The Tulsa massacre has been revisited on the HBO shows Watchmen and Lovecraft Country in recent years. And this month, which marks the centennial, is likely to see a deluge of media attention and symbolic gestures at remembering what was lost. But Nails-Alford, now in her early 60s and a career-services coordinator at the Tulsa Technology Center, doesn’t want her family’s legacy to be tied to these passing remembrances. She wants Greenwood’s pain—and its triumph—to be protected permanently.

There’s a tangible way to do that: by adding Greenwood to the National Register of Historic Places, the federal government’s official list of sites and structures deemed worthy of preserving for their historical significance. Little of the Greenwood that existed in 1921 is left standing; a place on the National Register would commemorate the rebuilding of the community after the massacre, and help residents and visitors remember what happened. It could also spur cultural and economic development: Being listed on the National Register is a prerequisite for garnering historic tax credits on the state and federal levels.

Nails-Alford has been trying for a few years to get her family’s land recognized. She has studied the requirements. She’s sent letters and emails and made phone calls, she told me. She’s sought the help of a historic-preservation expert, combed through records to trace the origins of her home, and asked city and state officials if “special consideration” could be granted. But the answer has consistently been no.

Nails-Alford’s efforts sit at the center of a larger problem: Decades of racial violence and gentrification have transformed Black neighborhoods across the country. But in many cases, these areas have been transformed so completely that the record of that struggle has been erased—and that makes it harder to preserve what’s still standing. In Greenwood, the physical proof necessary to qualify for the National Register was largely destroyed in the massacre and the decades of urban renewal that followed. Without that recognition, the neighborhood’s history is at risk of being distorted, or lost entirely.

Brenda Nails-Alford’s family came from Texas to Oklahoma—then Indian Territory—by way of covered wagon, part of a wave of Black settlers seeking new opportunities in the West. Black towns and communities—more than 50 in total—were popping up all over the state, and many were thriving. Greenwood was one of them: By 1921, the neighborhood had a population of 10,000, its own schools and hospital, and a bustling main street with movie theaters, restaurants, and a library. Most of Tulsa was white, but in Greenwood, Black residents found a place where most people looked like them; where the restaurateurs would serve them through the front door, not the kitchen; and where the money they spent circulated plenty of times before reaching the hand of a white Tulsan. Nails-Alford’s grandfather and his brother were running a successful chain of shoe and record stores in Greenwood, along with a limousine and taxi service and an event space.

The morning of May 30 of that year, a Black 19-year-old named Dick Rowland stepped into an elevator in downtown Tulsa with Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white elevator operator. At some point during the ride, Page screamed loudly enough to prompt a clerk to report the incident as an attempted assault. Though the exact details of what happened in that elevator aren’t known, what happened afterward was certainly influenced by stereotypes of what Black men do to white women: Rowland was arrested the next morning. Later that day, The Tulsa Tribune carried the headline “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator.”

By the time word reached Greenwood that Rowland was being held at the county courthouse, approximately 25 armed Black men, many of whom were veterans of the First World War, made their way there to protect him from being lynched. The sheriff turned them away, but later that night a group of about 75 Black men returned to the courthouse, where a white mob had swelled dramatically—estimates of its size range from roughly 1,000 to 2,000 people. As the Black men were getting ready to head back to their part of town, a Black man was accosted by a white man who was trying to take his gun away. As the argument peaked, a shot was fired and all hell broke loose.

Within hours, fires lit up Greenwood. Nails-Alford’s grandparents, Vasinora and James, along with her great-uncle Henry, fled for shelter in a park six miles northeast while their store was subsumed by the flames. Vasinora was pregnant, and their oldest child, Nails-Alford’s aunt, was 2 years old. Within less than 24 hours, the community lay in ruins.

All told, as many as 300 people died, nearly 10,000 were left homeless, and more than 1,000 homes and businesses were razed. It’s likely that many of those who died during and after the massacre were buried on top of other bodies, without a tombstone or any other marker to commemorate their lives. One and a half million dollars in property—more than $20 million in current dollars—was burned in less than a day.

Tulsa’s then mayor, T. D. Evans, created a reconstruction committee composed of the city’s political and business leaders. Rather than rebuilding the Black community that had flourished there, they worked to make room for a train station and an expanded railroad. Evans recommended that the “negro settlement be placed farther to the north and east.” And a week after the massacre, the city commission passed Fire Ordinance No. 2156, declaring that buildings could be rebuilt only if they met highly precise and costly specifications—two stories, made of concrete, brick, or steel—which would leave more land open for wealthy, white developers but would effectively limit most Black people from rebuilding homes. The ordinance was struck down in August, but no reparations were offered to finance rebuilding, and the damage was enormous. Most of that following winter, Black families were still warming themselves by the fires they made amid the rubble that once scaffolded homes.

Still, Greenwood residents rebuilt. Just four years later, in 1925, Greenwood hosted the National Conference of the National Negro Business League. According to Hannibal Johnson, the author of several books on Black Wall Street, “There [were] well over 200 documented black owned and operated businesses in the community. It was a thriving time in the Greenwood district in the 1940s.”

After half a century of growth, destruction, and restoration, Greenwood was knocked down again—this time by public policy. From the 1950s through the early 1970s, urban renewal granted cities federal funding to plow blighted areas—supposedly to clear a path for public-housing projects or other new buildings, though these projects displaced hundreds of thousands of people, predominantly people of color in low-income neighborhoods.

Nails-Alford can remember watching, as a child, fellow Greenwood residents protest as Black life in the neighborhood was gutted. Black businesses, schools, and family homes were destroyed and replaced with a highway that choked off the Greenwood community from the rest of the city but made it easier for mainly white families in the suburbs to commute to and from downtown Tulsa. Black residents made up 76 percent of the population loss in Greenwood and the surrounding areas by 1979.

It’s hard now to even imagine the community in which Nails-Alford grew up. She talked fondly about attending the Charles S. Johnson Elementary School, which was demolished in the mid-20th century and replaced with a satellite campus for Oklahoma State University. Her childhood home, which had been in the family since the early 1920s, was leveled in the urban-renewal era and replaced with a slightly refurbished house that had been built in 1940 and brought in from another part of the city. “A little paint was thrown on it,” she told me. “And that was called ‘renewal.’”

That newer house also sealed off the chances Nails-Alford had of getting her land listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

After Nails-Alford learned about the massacre in 2003, she started uncovering her family history. Her parents and grandparents had never talked about it, she said. She believes that their silence came from fear that discussing it could somehow conjure its recurrence—that those memories could be a trip wire to ignite racial terror once again. But Nails-Alford, as she put it, feels the need to “hold that history.” By 2018, she had dug up old deeds and titles; she’d heard about the National Register, and she thought she had what she needed to list her family’s land. She reached out to the Oklahoma Historical Society, but the process was cut short when they told her the property didn’t qualify: Although the land had been theirs for almost a century, if their original house was no longer there, it didn’t count—the lot itself wasn’t enough. Nails-Alford’s land was far from the only Black property that was ineligible.

In 1966, Congress passed the National Historic Preservation Act to preserve historic and archaeological sites. That act empowered the National Park Service to approve sites nominated by state historical-preservation offices, according to two main requirements. The site must be “significant,” meaning that it contributes to larger history. And its historical elements must be robust in “integrity,” meaning that the structure or site can ably convey its own historic significance. Integrity has seven components—location, setting, design, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association—each of which needs to be demonstrated and judged by the National Park Service. “Historic-preservation consultants” are often brought in to survey sites, take photos, and compile applications—and a single missing component can ruin a successful nomination.

The process is cumbersome, but the potential benefits can be significant. The National Park Service also offers a 20 percent tax credit for the rehabilitation and upkeep of historic buildings. In fiscal year 2018 alone, the NPS approved 1,013 of these projects, worth a total of $6.9 billion. Those tax credits can be a huge economic boost for communities that succeed in landing on the National Register. In fact, the NPS estimates that from 1978 to 2018, investment in historic-rehabilitation projects created approximately 2.7 million jobs and more than $176 billion in GDP. In Oklahoma, the prospects for economic gain are even greater: The state has its own historic tax credits too, which double the benefit for developers working with areas designated as historic.

But the recognition process consistently favors the whiter, wealthier neighborhoods, which are more likely to have been left intact. Brent Leggs, the executive director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, told me that of the approximately 100,000 entries listed on the National Register, only about 10 percent were chosen because they reflect “underrepresented social and ethnic communities.” And only about 2 percent were chosen because they reflect Black identity. Other places around the country that might reflect Black life in America—such as slave quarters, historic meeting places for Black families, and schools that once served Black children—have not usually garnered the attention of the preservation community. And when they have, their significance and physical integrity has often become compromised by years of degradation and development. “Preserved places,” according to Leggs, are usually associated with “a privileged few … mainly white plantation owners, white presidents, white businessmen and industrialists.”

Only months after Nails-Alford heard that her family’s land didn’t qualify for inclusion on the National Register, she learned that since the early 1980s a collection of Greenwood residents, property owners, and community organizations had been trying to get the entire neighborhood listed as a historic district. About a decade earlier, the group had met with Amanda DeCort, then the city of Tulsa’s historic-preservation planner. DeCort had an enviable track record of getting districts listed—particularly wealthier, whiter districts. Her work had been an engine of economic growth for the city. After talking with this group, she became fully committed to their cause.

But districts are particularly difficult to get listed on the National Register. The entire district must hold the level of significance and integrity that a single site might. Between its burning, its rebuilding, and its renewing—especially the highway through the middle of the community—Greenwood doesn’t maintain the contiguity that it once did. As an NPS official put it, Greenwood “has seen waves of redevelopment and change over time.”

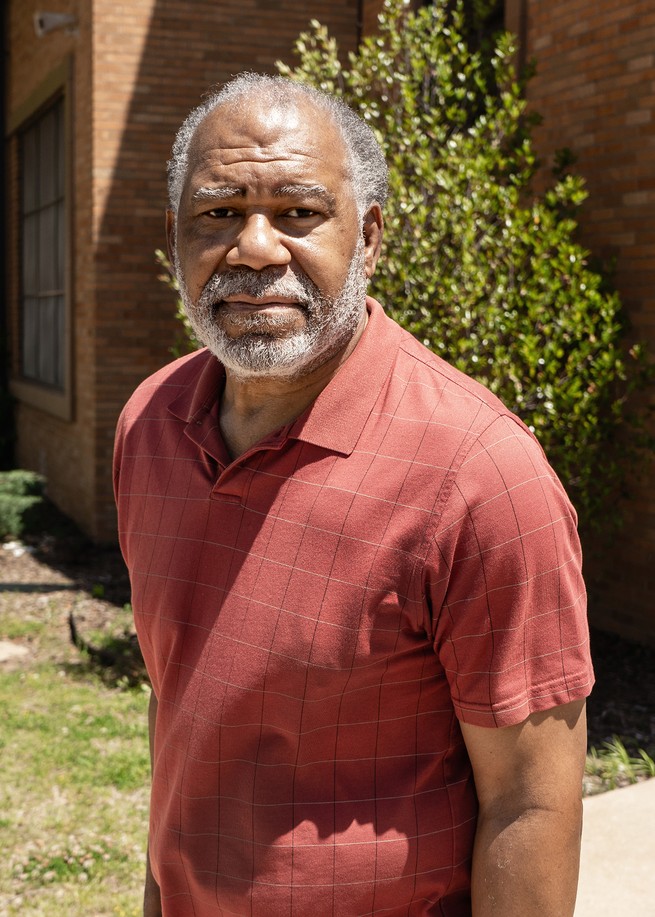

A state historic-preservation officer suggested that the group try to list Greenwood as a battlefield. But that proposal has continued to dismay community advocates—including Reuben Gant, the former head of the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce, who has worked for decades to develop a successful nomination for Greenwood. They do not want their community known only for a battle, placed in the “category of Gettysburg,” Gant told me. They want Greenwood remembered for all the ways in which it was successful, triumphant in spite of segregation, and devastated by massacre and renewal, but resilient most of all. After three unsuccessful nominations, the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce has proposed getting the small strip of the 100 blocks of Greenwood Avenue listed as a historical site. It could be a step in the right direction. But for people like Gant, it’s just a game of settling—and, as he said, it “is not historically accurate.”

For now, Greenwood’s remaining Black residents are watching the whiter parts of the city reap the benefits that come with National Register recognition: Thanks in large part to DeCort—and the districts lucky enough to become “historic”—$230 million was invested in rehabilitation projects in Tulsa through the tax-credit program from 2001 to 2015. These tax-credit projects led to almost $74.5 million in direct salary and wages.

Those credits could finance the upkeep of historical sections of Greenwood. So for Tulsa’s Black community, the lack of recognition has also stunted opportunities for continued remembrance. Fallon Aidoo, a professor of historic preservation at the University of New Orleans, told me that the whole process of seeking recognition on the National Register, only to be told that your community’s history has been too thoroughly destroyed to earn it, “reenacts violence over and over again” on the very people whom the state neglected to help in the first place.

These days, Nails-Alford can only rely on the fading memories she has from adolescence: a jewelry store, a drugstore, the hair salon down the street. And after three years of trying to get her family home listed, she can only allocate so much time to getting her stories memorialized. “Our community lost, through no fault of its own, twice,” she told me. Committed as she might be, she is exhausted.

On the 100th anniversary of the massacre, on May 31, we’ll hear about the dead who didn’t get proper burials, for whom Tulsans and archaeologists are still searching. We’ll watch documentaries and fictionalized accounts of what happened. But even as the massacre has entered public consciousness in a way it never has before, the day-to-day lives of Black Tulsans are still shaped by the ghosts of history and the knowledge that wrongs have not been righted. In that sense, Tulsa is unremarkable. Like much of America, it is starting to acknowledge its past. But it hasn’t begun to repair it.