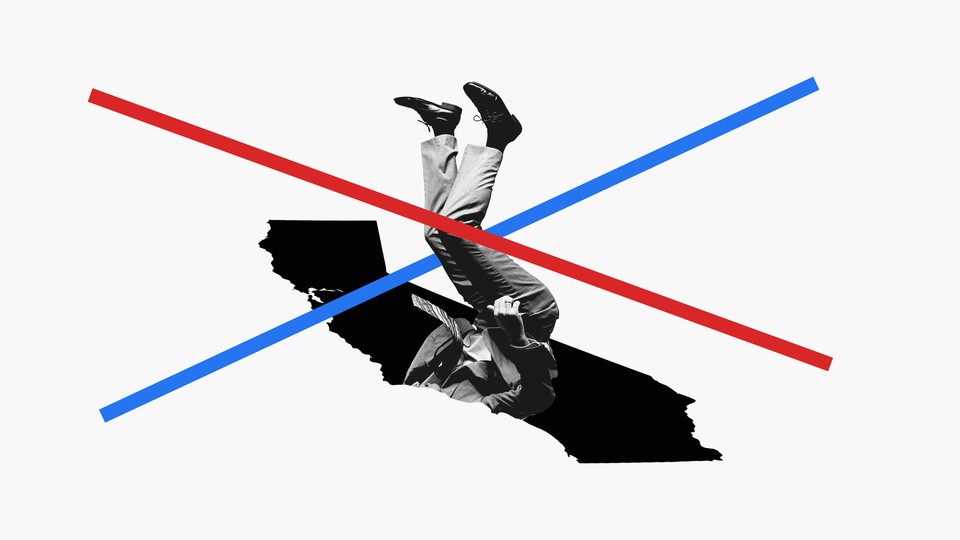

The Trouble With the Gavin Newsom Recall

The California law that gives voters the power to remove a sitting governor doesn’t make sense in an era of unrelenting partisan conflict.

The recall election coming later this year for California Governor Gavin Newsom doesn’t appear likely to end with his removal from office. Although Newsom’s opponents have gathered enough signatures to require a vote—and conditions in the state could still change—polls show that public support for the effort is far below what Newsom’s critics will need to force his removal.

Nevertheless, the drive may trigger another form of recall: It may finally prompt California to examine whether the 110-year-old state law that governs recalls still makes sense in our modern era of unrelenting partisan conflict.

The law was instituted during the Progressive era as a tool to tame special interests, but the effort against Newsom suggests that it’s become a weapon of harassment and manipulation by Republicans. The GOP constitutes a minority in the state, where Democrats hold all major statewide offices and supermajorities in both legislative chambers, and where Joe Biden buried Donald Trump by more than 5 million votes last year. Once California’s secretary of state gives final certification to the collected signatures, Newsom will become the second of the state’s past three Democratic governors to face a recall that reached the ballot: Governor Gray Davis was ousted in a 2003 recall election and replaced by Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger. How unusual is that confluence? Across all the states, recalls against only three other governors in American history have qualified for the ballot.

This pattern has some California Democrats now talking openly about making fundamental changes to the recall law—an idea rarely discussed since Governor Hiram Johnson, a Progressive icon, pushed it through the legislature in 1911. “This thing is going to be defeated by Newsom pretty handily,” says the Democratic strategist Garry South, who was the chief adviser to Davis in his two gubernatorial races, in 1998 and 2002. “And when this is all over, the legislature has to take a serious look at revamping the processes and procedures for qualifying a recall against the governor of California.”

California’s law establishes a two-step process for removing and replacing an executive-branch official. Once proponents collect enough signatures, the state schedules an election that asks voters two questions. First, they are asked to vote up or down on whether to recall the targeted official, in this case Newsom. Then, on the same ballot, they are asked to choose from a list of candidates who have filed to replace the official. (The incumbent’s name can’t be listed as an option.) If a majority votes no on the recall, that’s the end of it; the incumbent remains in office. But if a majority supports the recall, the incumbent is replaced by the alternative candidate who receives the highest vote total, even if that’s less than a majority (which is possible, given how large the candidate field often is).

Those rules create one of the first glaring anomalies in the California system: An incumbent could be removed and replaced even though a higher share of Californians vote to keep him in office than vote to support any single alternative. (For example, an incumbent could receive support from 49.9 percent of voters, but be ousted and replaced by someone who received a much smaller share of the vote.)

An even bigger anomaly is the threshold a recall effort needs to meet in order to qualify for the ballot. Nineteen states permit voters to recall a governor, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Among those states, California requires “the lowest [signature] total to recall any state governor in the country,” says Joshua Spivak, an expert on the recall process and a senior fellow at the Hugh L. Carey Institute for Government Reform at Wagner College, in New York. A recall can qualify for the ballot in California by collecting signatures equivalent to 12 percent of the votes cast in the previous gubernatorial election. Most states set a significantly higher bar, typically 25 percent.

In 2018, just under 12.5 million Californians voted in the gubernatorial election, in which Newsom swamped Republican John Cox by almost exactly 3 million votes. That meant recall proponents had to collect slightly fewer than 1.5 million signatures. In absolute terms, that’s a lot of signatures to obtain. Newsom critics launched four recall attempts before this, and all failed to meet that requirement. Even the current recall, launched by conservatives infuriated by Newsom’s COVID-19 shutdowns last spring, appeared to hit a wall in the fall. Then two important things happened on November 6: First, James Arguelles, a state superior-court judge appointed by Schwarzenegger, gave the proponents an unprecedented four-month extension to gather signatures, citing the difficulties created by the coronavirus. And on the same day, Newsom chose to attend a now-infamous birthday party for a lobbyist at a swanky restaurant in Napa Valley—a choice that became a flash point for voter frustration. Newsom’s attendance while much of California remained shut down “became a pop-culture caricature of what everyone hates about politicians,” says the Republican consultant Rob Stutzman, who served as Schwarzenegger’s communications director during the Davis recall and when Schwarzenegger was governor. “It had everything: It had elitism, it had hypocrisy, it had a whiff of pay-to-play.”

With the extra time and the spark Newsom lit with his restaurant blunder, money poured in from Republican donors, and the signature drive was revived. Funds were now available to hire professional canvassers and send direct mail to voters to collect signatures. The 1.5 million signatures required represents a small fraction of the reliable GOP vote in the nation’s largest state. Cox won just 38 percent of the total vote in his 2018 bid against Newsom, but that amounted to more than 4.7 million votes. Trump, while winning just 34 percent of California’s total vote last year, attracted more than 6 million.

All evidence suggests that those same Republican voters are primarily powering the recall effort now. A recent Los Angeles Times analysis found the greatest support for the effort in the state’s residual red regions: the rural northeastern and Central Valley counties “with low coronavirus case counts and where voters heavily favored former President Trump.”

Another revealing measure of support for the effort is how many recall signatures each county produced per vote cast in the 2020 presidential election: The 19 counties that ranked highest on that measure all voted for Trump last year. Meanwhile, most of the state’s major urban and suburban population centers—including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Santa Clara, and Alameda Counties—ranked at the very bottom of that list (with the signatures gathered there equaling 6 percent or less of their total 2020 turnout). In a statewide poll released this week by UC Berkeley and the L.A. Times, 85 percent of Republicans said they support recalling Newsom, compared with 33 percent of independents and only 8 percent of Democrats. That puts overall support for Newsom’s removal at 36 percent—midway between the meager GOP votes for Cox in 2018 and Trump in 2020.

All of this raises a key question: whether the recall is measuring a genuine eruption of grassroots discontent against Newsom or merely recording the fact that many of the Republican voters who never wanted him to be governor still don’t. At times last year, the former explanation seemed somewhat plausible, with the virus imposing terrible economic and health losses on the state. But the latter looks much more convincing now, as the state’s infection and hospitalization rates have plummeted, the economy is reopening, vaccination totals are rising, and the state’s budget is recovering. Dan Schnur, a former Republican operative who now teaches at UC Berkeley and the University of Southern California, agrees that the recall effort at this point is mostly measuring conservative alienation in a state that has shifted emphatically toward Democrats since the 1990s. “There are a lot of voters who are unhappy with the way Newsom has handled the pandemic, but not nearly enough to remove him from office,” Schnur told me. Indeed, in the new UC Berkeley/L.A. Times poll, only 35 percent of voters gave Newsom poor marks for his handling of the pandemic—roughly the same minority that backs the recall.

It’s useful to compare Newsom’s circumstances with that of another Democrat, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. In a state that is much more closely divided between the parties, Whitmer faced an even more ferocious right-wing backlash against her COVID-19 restrictions last year. (That backlash included a protest by armed activists who descended on the state capitol and a plot to kidnap and possibly murder her.) Critics have filed nine separate petitions to recall her from office. But because Michigan requires twice as many signatures as California for a recall to reach the ballot—25 percent versus 12 percent—none of those efforts is likely to qualify.

In one sense, this contrast might not have troubled the Progressive-era leaders who created the recall law in California. “They didn’t want it to be hard to use,” Glen Gendzel, the chair of San Jose State University’s history department, who has studied that era in the state, told me. The recall was part of an extraordinary package of 22 state constitutional amendments—including the initiative and referendum processes—that Hiram Johnson persuaded voters to approve in a single election in October 1911. The unifying thread among those measures was Johnson’s determination to create safeguards against the corrupting power of the Southern Pacific Railroad, the dominant economic and political force in the state at the time. Progressives thought “they only had one chance to enact laws in a great big hurry that would ensure the capability to resist further corruption of California government once the Progressives were out of power,” Gendzel said. “What are you going to do if corrupt politicians return to power and serve the main special interest in the state again, namely the railroad? Well, make it possible for the people to recall them, to pull them out, if they prove unfaithful to the people’s wishes.”

Johnson and his allies tended to see politics in terms of interests, not parties; they sought to unite both Democratic and Republican Progressives against Southern Pacific’s concentrated economic power. Although elected as a Republican, Johnson bolted from the party to run as Theodore Roosevelt’s vice president in his unsuccessful third-party Progressive presidential bid in 1912, and when he returned to California, Johnson passed legislation to transform state elections into nonpartisan contests, Gendzel noted. (Ironically, a referendum sponsored by Republican and Democratic party bosses, using the Progressives’ own direct-democracy tools, overturned that law.) The recall as a deliberately partisan weapon probably would have stunned Johnson.

Like many other features of America’s electoral system, including the Electoral College, the California recall is buckling under the pressure of today’s hyper-partisanship. Johnson envisioned the recall as a tool for a majority of “the people” to protect themselves against a minority of “the interests.” But today it’s a minority of disaffected Republicans who are trying to overturn the majority’s vote. No Republican has won any major statewide office in California since 2006. A recall gives them better odds than a conventional election, partly because of the unusual up-down vote on the incumbent, and partly because turnout for special elections is so unpredictable.

“I don’t think the Progressives could have anticipated a situation like this,” Gendzel said, “where one party is repeatedly repudiated at the polls … and they simply use their financial advantages to force a redo … in which they hope to prevail because the conditions are different.”

Critics of the current law are beginning to discuss several options for changing California’s recall process. Among them are requiring proponents to prove some standard of malfeasance before placing a recall on the ballot (as seven of the 19 states with recall laws now require); allowing the incumbent to run on the replacement ballot; or simply raising the threshold of signatures required to qualify. The conventional wisdom in the state is that persuading voters to surrender any of the authority they currently have under the recall law will be extremely difficult, especially because any major changes would require a constitutional amendment. “I don’t think Newsom should be removed from office, but boy would I not want to run the campaign to make a recall harder to achieve,” Schnur said.

Yet other political observers believe that a failed recall against Newsom could trigger a reconsideration of the law. Political experts in both parties caution that the drive against Newsom could become a much closer call if conditions turn against him before the vote—if there’s a resurgence of the virus, extensive problems with the power grid or wildfires, or a wide-scale disruption to the reopening of schools in the fall, to name some examples. But if conditions remain steady or improve and the recall is resoundingly rejected, it may be possible to persuade both Democratic legislators and voters to back changes. “You have to tighten up these procedures and processes to make sure this is not some frivolous alternative that Republicans are using to gain power in California because they can’t win fair and square at the ballot box,” South told me.

Stutzman says that, after the Newsom experience, even Republicans should support retrenching the recall law. The threat the law poses to incumbents “would manifest itself even more acutely” if and when Republicans next elect a governor in the blue stronghold. “All of a sudden, a nurses’ union or teachers’ union could go out and do this to them,” he said. “Republicans should be in support of reform, because it would ultimately offer them more protection if they ever retake the office.”

California Republicans seem unlikely to heed that counsel. California Democrats, meanwhile, face a dynamic similar to the one confronting the national party in the raging battle over ballot access. Facing clear evidence that GOP governors and legislatures are rewriting voting laws in red states to hurt Democratic prospects, congressional Democrats still haven’t used their power to preempt that offensive with federal voting-rights legislation. California Democrats might be equally guilty of political malpractice if they don’t try to change the recall law while they have the power to do so, with clear indication from the GOP that Republicans will wield it as a weapon every chance they get.