America’s New Vision of Astronauts

Once, American astronauts were white men with buzz cuts. Now they’re billionaires and a few lucky normal people.

The mission had gone smoothly from start to finish. “Thanks for flying SpaceX,” an engineer said as the spaceship splashed back down to Earth, prompting laughs in the mission-control room. SpaceX’s passengers, Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken, were experienced spacefarers, trained and employed by NASA, but they were the first people the private company had launched into orbit. The line was heavy with relief—we did it; we brought these astronauts home—and hope, the feeling of a long-distant goal coming into view. This could be the first of many flights, not just for astronauts, but for regular folks too.

Less than a year later, SpaceX is already planning to jump into that next era of spaceflight.

Elon Musk announced yesterday that the company will send four non-astronauts into orbit around Earth for a few days, perhaps as soon as the end of this year. The mission, the first all-civilian trip of its kind, will be led by Jared Isaacman, a founder and the CEO of Shift4 Payments, a payment-processing company.

Isaacman has chartered a SpaceX rocket and a Crew Dragon capsule for himself and three other passengers, and will serve as mission commander. He is a 37-year-old tech billionaire and a licensed pilot who knows how to fly fighter jets, but he has never been to space. Neither have the other passengers.

One passenger, whom Isaacman has already picked, is a health-care worker who works with children with cancer, and she’s a cancer survivor herself. Another will be randomly selected this month in a raffle meant to raise millions of dollars for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. The final passenger will be chosen in an online competition organized by Isaacman’s company.

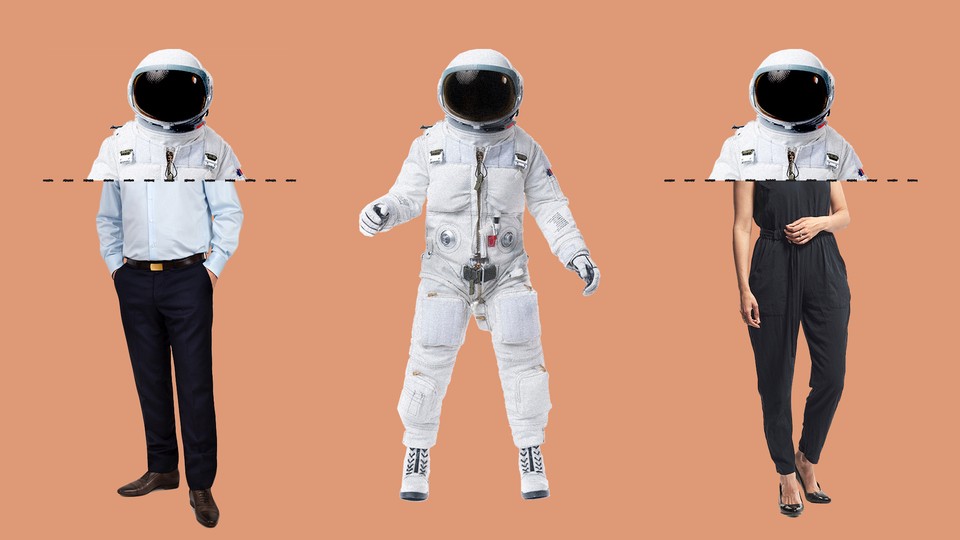

When they step onto SpaceX’s craft, they will become a crew unlike any other in history. The question of who can be an astronaut has never been more open-ended. Half a century ago, the people who decided who went to space worked at NASA and other space agencies. Now they’re people rich enough to see the beauty of Earth against the darkness of space for themselves, and rich enough to decide who should come with them.

So unprecedented is this situation that when a reporter asked Musk at a recent press conference about how SpaceX plans to handle liability insurance for this kind of adventure, Musk wasn’t sure. “I think this may be [an] ‘at their own risk’ type of thing,” he said. “I don’t know.”

Astronauts have always been selected to represent a certain vision of America. In the beginning, they all worked for NASA. They had flown combat missions in wars. They were white men with buzz cuts. In the early 1960s, a Black Air Force pilot was in the running to become a NASA astronaut, but his training was marred by racism, and the agency didn’t select him, never providing an explanation why. Around the same time, John Glenn, the first American to orbit Earth, said in a congressional hearing about gender discrimination in NASA’s astronaut program: “The men go off and fight the wars and fly the airplanes and come back and help design and build and test them. The fact that women are not in this field is a fact of our social order.” Twenty-four people have flown to the moon, and all were white men.

Over the years, this vision of astronauts has shifted. The first Black American and the first American woman flew on the space shuttle in 1983. Space-shuttle assignments eventually moved beyond historic firsts and toward diverse crews. NASA stopped referring to space travel as “manned,” favoring the more inclusive “crewed” or “human.” Last month, NASA announced which of its astronauts will train specifically for a future moon mission; of the 18, half are women.

Private citizens have flown to space before, but they have always gone on government-owned spacecraft, and with trained astronauts at their side. They were simply rich enough to afford it, paying about $20 million for the voyage. Two American politicians flew on the shuttle in the 1980s, but they had something else going for them: Both men sat on the congressional committees in charge of NASA’s budget.

Last week, it was announced that three people had paid $55 million each for SpaceX to fly them to the International Space Station for an eight-day visit, accompanied by a former astronaut. Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’s space company, reportedly plans to charge $200,000 to $300,000 for trips to the edge of space, where passengers can experience a few minutes of weightlessness. Virgin Galactic, Richard Branson’s company, will charge $250,000 for flights on its fleet of rocket-powered planes. (Virgin Galactic has already flown a few of its employees high into the atmosphere and into weightlessness, and while they didn’t reach orbit, the Federal Aviation Administration, which regulates space launches, considers them commercial astronauts.)

Isaacman won’t say how much he’s paying to charter his historic mission, but you can certainly bet it’s a lot. The billionaire has introduced another factor into the criteria for being an astronaut—luck. There are still some basic restrictions, such as passing a medical screening and meeting height requirements for the cramped Dragon capsule. (“If you can go on a roller-coaster ride, like an intense roller-coaster ride, you should be fine for flying on Dragon,” Musk said.) Isaacman’s company plans to run a commercial during this weekend’s Super Bowl to advertise the mission, a PR move NASA has never tried. In the case of one of Isaacman’s passengers, the decision makers will be “a panel of independent judges” choosing who did the best job in an online competition involving something called the “Shift4Shop eCommerce platform.”

The financial prerequisites for spaceflight threaten to again narrow the population of people who get to go to space—the three passengers who paid $55 million for their SpaceX rides are all white men—but Isaacman said that he’s aware the composition of his crew will send a message about who space is for. “This absolutely will be diverse,” Isaacman said of his mission’s crew.

Isaacman and the other passengers will receive formal training from SpaceX, including emergency simulations. The Dragon capsule operates with more autonomy than perhaps any other crewed spacecraft in history; when Hurley and Behnken launched from Cape Canaveral last year, SpaceX flight software piloted them to the ISS. The astronauts took over manual control and maneuvered the capsule for a bit, to see how it handled, but the Dragon didn’t need their assistance to gently dock to the station.

SpaceX has so far flown six professional astronauts, and more are scheduled to launch this spring. By the time Isaacson and his crew launch, the SpaceX astronaut program will be quite flight-tested and astronaut-approved. It will even be—and this is a remarkable thing to say about space travel—a little customizable. More than once on the recent call with reporters, Musk deferred to Isaacman on questions about mission specifics such as the duration of the journey. “The mission parameters are up to Jared,” Musk said, before addressing the soon-to-be mission commander: “If you decide later you want to do a different mission, you totally can.”

The rest of the press conference was similarly casual, even lighthearted. When Isaacman said that he would prepare the crew for Dragon’s cramped quarters by making them spend time together in a mountainside tent, Musk joked that “everyone’s got to eat a giant bean burrito.” One reporter asked whether SpaceX would bend some space-travel rules and allow passengers to bring champagne. This mood should not give anyone a false impression about human spaceflight. SpaceX might be ready to launch people into space on a regular basis, but that doesn’t mean the work is routine. It’s still dangerous.

SpaceX knows this; over the years, employees have received briefings about the aftermath of the two space-shuttle disasters, which together killed 14 astronauts, and the launchpad fire during the Apollo program that killed three. “We hold the lives of people in our hands,” Benji Reed, the senior director for human-spaceflight programs at SpaceX, told me last year. “We take it very, very seriously.” The big reveal of Isaacman’s mission coincided with the 17th anniversary of the Columbia disaster. In the past, astronauts have matched the risk of spaceflight with a sense of mission, as representatives of nations. Any personal excitement about leaving the planet was buoyed by a feeling of duty. When Isaacman and the rest of his crew strap in, they will be taking similar risks, but for new reasons.