The Original Kings of Esports

Black players pioneered what we now call esports. The industry hasn’t paid them back.

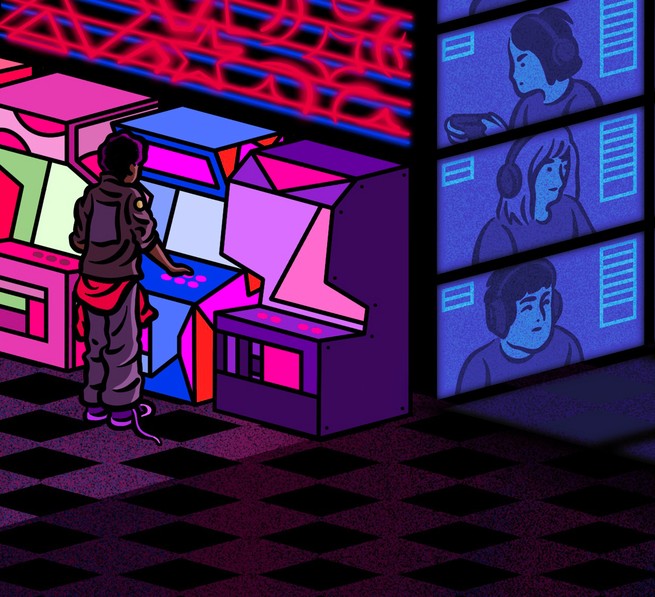

Jason Cole didn’t own a computer, but he was fairly certain that he was the best Street Fighter player in California. It was the early 1990s, and Cole often found himself with a pocketful of quarters at the Golfland arcade in San Jose. Standing in front of a crusty Street Fighter II cabinet, he would take on an endless stream of competitors, from clueless middle schoolers to yuppies on their lunch break, and beat them all. Most who encountered Cole quickly found themselves 25 cents poorer. He was just too good.

This was long before esports morphed into the industry it is today. Cole wasn’t competing for million-dollar prize pools or hefty sponsorships, or international fame. All he wanted—all he could reasonably hope for—was dominion over his local arcade.

So you can understand why Cole took it personally when a cadre of Street Fighter players from the other end of the state—Los Angeles, in particular—started doubting his talent. On ancient web forums, they claimed that Cole’s game would never hold up in SoCal, that his gambits could be easily countered by any player worth their salt. Because Cole had no internet access, he relied on a network of friends who relayed the message-board slander. It was confirmation that his legend had grown far beyond the Bay Area and, more important, that he still had something to prove.

“I had to hear it from the homies—my boys had to tell me what was going on,” Cole remembers now. “The L.A. guys would start coming up here, or we’d go down there. You just wanted to try your style against other people.”

This was the genesis of what we now refer to as the fighting-game community, or FGC, which remains one of the oldest fixtures in competitive gaming: one-against-one battles in games such as Mortal Kombat, Marvel vs. Capcom, and Cole’s speciality, Street Fighter. These games were much more technical than your Marios and your Zeldas. They came with intricate button inputs and rewarded precise timing. In the mid-’90s, you could claim to be the best Street Fighter player and have that actually mean something. Fighting-game hot spots popped up around the country. Some of the earliest esports kings were crowned at Chinatown Fair in New York City, Super Just Games outside Chicago, and the Southern Hills Golfland in Orange County. As the scene grew, and the regional smack talk percolated, these fledgling gamers felt the need to settle scores.

And so, in 1996, Cole and 63 other competitors ventured to the Sunnyvale Golfland for Battle by the Bay. It was a true watershed moment for esports, and it originated entirely out of grassroots momentum. The makeup of the contestants reflected the culture nurtured by the arcades. Battle by the Bay was organized by twin brothers named Tom and Tony Cannon, who are Black. Alex Valle, one of the original icons of the scene, was born in Peru. John Choi, Cole’s Bay Area rival at the time, was born in Korea. And Cole himself competed under the name “AfroCole”—a not-at-all-subtle reference to his haircut of choice. Looking back, Battle by the Bay is a snapshot of the brilliant optimism of esports during its earliest days. Whether the people there knew it at the time, a new sport and a new industry were being invented, and by a diverse group, melded together in the meritocracy of punches, blocks, and whirlwind kicks.

“We didn’t care who stepped up to the mic. There was no hate. If you were a female, if you were a little kid, whatever race you were, it didn’t matter,” Cole told me. “It was a beautiful thing.”

The esports industry has long outgrown Sunnyvale. Last year, at the world championship for the multiplayer strategy game League of Legends, 22 teams competed for shares of a prize pool valued at at least $2 million. Esports has welcomed a windfall of corporate financing and licensing. Billionaire dynasts, such as the Cleveland Cavaliers owner Dan Gilbert and New England Patriots CEO Robert Kraft, have invested heavily. Riot Games, the developer and publisher of League of Legends, has negotiated lucrative deals with mainstream brands such as Verizon and Honda. Business Insider reported that the industry is expected to surpass $1.5 billion in revenue by next year. For the first time in history, it pays to be a gamer.

Yet if you browse the rosters of the teams competing in League of Legends’ 2021 North American season, you will find only a single Black player. Overwatch League has had only a few Black players in its ranks since the league’s founding, in 2017. You’ll find similar numbers in the leagues for the multiplayer strategy game Dota 2, the first-person shooter Counter-Strike, and the digital card game Hearthstone. Instead, Black esports pros are most often represented in the world they helped build: the FGC.

At the 2019 edition of EVO, the premier fighting-game tournament, which grew out of Battle by the Bay, at least nine Black players across eight different titles scored top-10 finishes. One of those players, Dominique “SonicFox” McLean, came in first and second in two separate games. (McLean was named ESPN’s Player of the Year in 2018.) Black kids never stopped excelling at esports, but they’ve been offered a seat at the table in only a select few leagues.

And by and large, the games that Black players continue to dominate don’t have nearly the same financial support as others. At the 2019 Capcom Cup, a championship for Street Fighter, two Black players—Derek “iDom” Ruffin and Victor “Punk” Woodley—squared off for a $250,000 payout. The International, the world-championship tournament for Dota 2, offered a $34 million prize pool at its 2019 event.

Esports is a young field. It doesn’t carry nearly the same painful, prejudiced history that sullies the legacies of MLB, the NFL, and the NBA. In fact, most professional gaming leagues are less than a decade old and simply haven’t had the time to accumulate much baggage. That makes the diversity problem paradoxical: How did a familiar racial partition afflict the spry, modernized esports industry?

To answer that question, Jason Cole reminded me that he didn’t grow up with a computer.

“You’re a product of a situation. The reason fighting games were so diverse was because it was so accessible. You walk down to your local 7-Eleven, your local mall, anywhere that has an arcade cabinet set up. It was always accessible for every minority,” he said. “You see the lack of representation in all these PC esports games now, and that’s because a lot of these cats didn’t grow up with that kind of technology.”

Cole was touching on one of the most important distinctions in esports. The competitive games with an overwhelming lack of Black players all tend to fall in the same category. They are team-based, with about five players per side. Some are released exclusively for PCs, and competitors tend to connect to all of their matches online. This setup is naturally prohibitive to kids without a dedicated computer or sturdy Wi-Fi. A game like League of Legends can run on a computer as lightweight as a Chromebook, but making that work might require a convoluted process (like, say, switching the operating system to Linux). Those prohibitions affect a wide swath of the population. According to data from the New American Economy, nearly 40 percent of Black households lack personal broadband-internet access, compared with 26 percent of white households. Meanwhile, all Street Fighter asks for is a few quarters or a Playstation and a pair of controllers.

“One group had the accessibility to really practice and grind on their computers,” Cole said. “And we had the accessibility to really practice and grind in the arcade.”

Ryan Hart is a 42-year-old fighting-game legend who holds the Guinness World Record for the most international fighting-video-game competition wins. Hart is Black, and was homeless for a period during his teenage years. Fighting games, and the sanctuary of the arcade, gave him a community. “It’s like going to a bar or a pub,” Hart told me. “Arcades are public houses.” He brought up Counter-Strike: An average match requires 10 total players, and therefore organizing a contest would require 10 individual computers. Hart contrasted that with the simplicity of fighting games, which can be played with an “old TV from the garage and a console.”

“You’re good to go. You could run a tournament with 64 or 128 competitors with that arrangement,” he continued. “It might take a long time, but you’re good. You didn’t need a streaming setup, or headphones, or anything. You just ran the audio out of the speakers and everyone got hype around the screen. It was completely different. Even those little things played a part in inviting people into fighting games.”

Everyone I spoke with for this story talked about these socioeconomic barriers when asked to diagnose esports’ diversity problem. It’s tempting to think of segregation as the direct result of individual actors, but the truth is as banal and as intractable as what kind of computer someone has at home. Not even esports—an industry built from the ground up, over the past three decades—can escape the centrifugal force of structural inequality. Racism can determine where people live and what jobs they have. Why wouldn’t it also arbitrate what video games they’re allowed to play?

That’s not to diminish the direct, confrontational racism that Black gamers in predominantly white spaces have experienced in their careers. In 2016, Terrence Miller, then a professional Hearthstone player, placed second in an international tournament in Austin, Texas. The audience on the live-streaming platform Twitch bombarded the chat box with racially coded emoticons and outright slurs whenever he appeared on-screen.

“When I played Yu-Gi-Oh [a competitive card game similar to Hearthstone], I was mostly playing around Brooklyn and New York, which is pretty accepting of all races. There’s all kinds in New York, and I never got anything just based on my race,” Miller told me shortly after his victory five years ago. “But in Hearthstone, the people at the top aren’t as diverse, and that’s why there’s so much attention on it. So I’ve gotten attention that’s not just because of my play; it’s because of my race. And I’d prefer that it wasn’t that way.”

Miller also noted that some Hearthstone tournaments are invitationals, meaning that, unlike with qualifier events, organizers can potentially invite whomever they want—but they largely haven’t taken the opportunity to broaden the playing field, which still skews heavily male and non-Black. No matter how good of a player you might be, you’re still up against the institution.

There is some hope that the next generation of esports pros will be more diverse, as access to computers becomes more common around the world. At the same time, stories like Ryan Hart’s and Jason Cole’s, about a bunch of kids crowding around an arcade cabinet until twilight, are fading further into the distance. The competitive community was small back then; live-streaming networks like Twitch didn’t exist. Esports is an industry obsessed with newness, and one that’s often more interested in reinventing the wheel than revisiting the past. All that survives are a few message-board posts and some veterans still willing to talk about their glory days. The history of the early days of fighting games—and many of the Black and brown faces that helped frame it—has been effectively forgotten.

I asked Hart about this toward the end of our conversation. He doesn’t mind if players coming up today don’t know about the decades-long traditions of competitive gaming. In fact, Hart believes that in many ways fighting games exist in their own lineage—separate from League of Legends, Counter-Strike, and the esports industry in general. The only thing that annoys Hart is when players dismiss the past entirely.

“When people try to negate history to make themselves more relevant, or their talking point more relevant, that gets on my nerves,” he said. “We can learn a lot from history.”