The Liberals Who Can’t Quit Lockdown

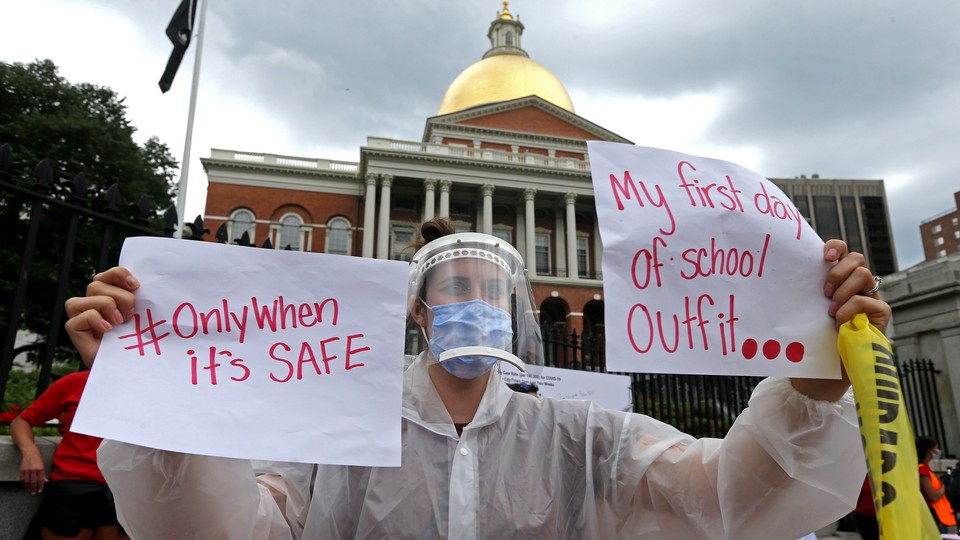

Progressive communities have been home to some of the fiercest battles over COVID-19 policies, and some liberal policy makers have left scientific evidence behind.

Lurking among the jubilant Americans venturing back out to bars and planning their summer-wedding travel is a different group: liberals who aren’t quite ready to let go of pandemic restrictions. For this subset, diligence against COVID-19 remains an expression of political identity—even when that means overestimating the disease’s risks or setting limits far more strict than what public-health guidelines permit. In surveys, Democrats express more worry about the pandemic than Republicans do. People who describe themselves as “very liberal” are distinctly anxious. This spring, after the vaccine rollout had started, a third of very liberal people were “very concerned” about becoming seriously ill from COVID-19, compared with a quarter of both liberals and moderates, according to a study conducted by the University of North Carolina political scientist Marc Hetherington. And 43 percent of very liberal respondents believed that getting the coronavirus would have a “very bad” effect on their life, compared with a third of liberals and moderates.

Last year, when the pandemic was raging and scientists and public-health officials were still trying to understand how the virus spread, extreme care was warranted. People all over the country made enormous sacrifices—rescheduling weddings, missing funerals, canceling graduations, avoiding the family members they love—to protect others. Some conservatives refused to wear masks or stay home, because of skepticism about the severity of the disease or a refusal to give up their freedoms. But this is a different story, about progressives who stressed the scientific evidence, and then veered away from it.

For many progressives, extreme vigilance was in part about opposing Donald Trump. Some of this reaction was born of deeply felt frustration with how he handled the pandemic. It could also be knee-jerk. “If he said, ‘Keep schools open,’ then, well, we’re going to do everything in our power to keep schools closed,” Monica Gandhi, a professor of medicine at UC San Francisco, told me. Gandhi describes herself as “left of left,” but has alienated some of her ideological peers because she has advocated for policies such as reopening schools and establishing a clear timeline for the end of mask mandates. “We went the other way, in an extreme way, against Trump’s politicization,” Gandhi said. Geography and personality may have also contributed to progressives’ caution: Some of the most liberal parts of the country are places where the pandemic hit especially hard, and Hetherington found that the very liberal participants in his survey tended to be the most neurotic.

The spring of 2021 is different from the spring of 2020, though. Scientists know a lot more about how COVID-19 spreads—and how it doesn’t. Public-health advice is shifting. But some progressives have not updated their behavior based on the new information. And in their eagerness to protect themselves and others, they may be underestimating other costs. Being extra careful about COVID-19 is (mostly) harmless when it’s limited to wiping down your groceries with Lysol wipes and wearing a mask in places where you’re unlikely to spread the coronavirus, such as on a hiking trail. But vigilance can have unintended consequences when it imposes on other people’s lives. Even as scientific knowledge of COVID-19 has increased, some progressives have continued to embrace policies and behaviors that aren’t supported by evidence, such as banning access to playgrounds, closing beaches, and refusing to reopen schools for in-person learning.

“Those who are vaccinated on the left seem to think overcaution now is the way to go, which is making people on the right question the effectiveness of the vaccines,” Gandhi told me. Public figures and policy makers who try to dictate others’ behavior without any scientific justification for doing so erode trust in public health and make people less willing to take useful precautions. The marginal gains of staying shut down might not justify the potential backlash.

Even as the very effective COVID-19 vaccines have become widely accessible, many progressives continue to listen to voices preaching caution over relaxation. Anthony Fauci recently said he wouldn’t travel or eat at restaurants even though he’s fully vaccinated, despite CDC guidance that these activities can be safe for vaccinated people who take precautions. California Governor Gavin Newsom refused in April to guarantee that the state’s schools would fully reopen in the fall, even though studies have demonstrated for months that modified in-person instruction is safe. Leaders in Brookline, Massachusetts, decided this week to keep a local outdoor mask mandate in place, even though the CDC recently relaxed its guidance for outdoor mask use. And scolding is still a popular pastime. “At least in San Francisco, a lot of people are glaring at each other if they don’t wear masks outside,” Gandhi said, even though the risk of outdoor transmission is very low.

Scientists, academics, and writers who have argued that some very low-risk activities are worth doing as vaccination rates rise—even if the risk of exposure is not zero—have faced intense backlash. After Emily Oster, an economist at Brown University, argued in The Atlantic in March that families should plan to take their kids on trips and see friends and relatives this summer, a reader sent an email to her supervisors at the university suggesting that Oster be promoted to a leadership role in the field of “genocide encouragement.” “Far too many people are not dying in our current global pandemic, and far too many children are not yet infected,” the reader wrote. “With the upcoming consequences of global warming about to be felt by a wholly unprepared worldwide community, I believe the time is right to get young scholars ready to follow in Dr. Oster’s footsteps and ensure the most comfortable place to be is white [and] upper-middle-class.” (“That email was something,” Oster told me.)

Sure, some mean people spend their time chiding others online. But for many, remaining guarded even as the country opens back up is an earnest expression of civic values. “I keep coming back to the same thing with the pandemic,” Alex Goldstein, a progressive PR consultant who was a senior adviser to Representative Ayanna Pressley’s 2018 campaign, told me. “Either you believe that you have a responsibility to take action to protect a person you don’t know or you believe you have no responsibility to anybody who isn’t in your immediate family.”

Goldstein and his wife decided early on in the pandemic that they were going to take restrictions extremely seriously and adopt the most cautious interpretation of when it was safe to do anything. He’s been shaving his own head since the summer (with “bad consequences,” he said). Although rugby teams have been back on the fields in Boston, where he lives, his team still won’t participate, for fear of spreading germs when players pile on top of one another in a scrum. He spends his mornings and evenings sifting through stories of people who have recently died from the coronavirus for Faces of COVID, a Twitter feed he started to memorialize deaths during the pandemic. “My fear is that we will not learn the lessons of the pandemic, because we will try to blow through the finish line as fast as we can and leave it in the rearview mirror,” he said.

Progressive politics focuses on fighting against everyday disasters, such as climate change and poverty, struggles that may shape how some people see the pandemic. “If you’re deeply concerned that the real disaster that’s happening here is that the social contract has been broken and the vulnerable in society are once again being kicked while they’re down, then you’re going to be hypersensitive to every detail, to every headline, to every infection rate,” Scott Knowles, a professor at the South Korean university KAIST who studies the history of disasters, told me. Some progressives believe that the pandemic has created an opening for ambitious policy proposals. “Among progressive political leaders around here, there’s a lot of talk around: We’re not going back to normal, because normal wasn’t good enough,” Goldstein said.

In practice, though, progressives don’t always agree on what prudent policy looks like. Consider the experience of Somerville, Massachusetts, the kind of community where residents proudly display rainbow yard signs declaring In this house … we believe science is real. In the 2016 Democratic primary, 57 percent of voters there supported Bernie Sanders, and this year the Democratic Socialists of America have a shot at taking over the city council. As towns around Somerville began going back to in-person school in the fall, Mayor Joseph Curtatone and other Somerville leaders delayed a return to in-person learning. A group of moms—including scientists, pediatricians, and doctors treating COVID-19 patients—began to feel frustrated that Somerville schools weren’t welcoming back students. They considered themselves progressive and believed that they understood teachers’ worries about getting sick. But they saw the city’s proposed safety measures as nonsensical and unscientific—a sort of hygiene theater that prioritized the appearance of protection over getting kids back to their classrooms.

With Somerville kids still at home, contractors conducted in-depth assessments of the city’s school buildings, leading to proposals that included extensive HVAC-system overhauls and the installation of UV-sterilization units and even automatic toilet flushers—renovations with a proposed budget of $7.5 million. The mayor told me that supply-chain delays and protracted negotiations with the local teachers’ union slowed the reopening process. “No one wanted to get kids back to school more than me … It’s people needing to feel safe,” he said. “We want to make sure that we’re eliminating any risk of transmission from person to person in schools and carrying that risk over to the community.”

Months slipped by, and evidence mounted that schools could reopen safely. In Somerville, a local leader appeared to describe parents who wanted a faster return to in-person instruction as “fucking white parents” in a virtual public meeting; a community member accused the group of mothers advocating for schools to reopen of being motivated by white supremacy. “I spent four years fighting Trump because he was so anti-science,” Daniele Lantagne, a Somerville mom and engineering professor who works to promote equitable access to clean water and sanitation during disease outbreaks, told me. “I spent the last year fighting people who I normally would agree with … desperately trying to inject science into school reopening, and completely failed.”

In March, Erika Uyterhoeven, the democratic-socialist state representative for Somerville, compared the plight of teachers to that of Amazon workers and meatpackers, and described the return to in-person classes as part of a “push in a neoliberal society to ensure, over and above the well-being of educators, that our kids are getting a competitive education compared to other suburban schools.” (She later asked the socialist blog that ran her comments to remove that quote, because so many parents found her statements offensive.) In Somerville, “everyone wants to be actively anti-racist. Everyone believes Black lives matter. Everyone wants the Green New Deal,” Elizabeth Pinsky, a child psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital, told me. “No one wants to talk about … how to actually get kindergartners onto the carpet of their teachers.” Most elementary and middle schoolers in Somerville finally started back in person this spring, with some of the proposed building renovations in place. Somerville hasn’t yet announced when high schoolers will go back full-time, and Curtatone wouldn’t guarantee that schools will be open for in-person instruction in the fall.

Policy makers’ decisions about how to fight the pandemic are fraught because they have such an impact on people’s lives. But personal decisions during the coronavirus crisis are fraught because they seem symbolic of people’s broader value systems. When vaccinated adults refuse to see friends indoors, they’re working through the trauma of the past year, in which the brokenness of America’s medical system was so evident. When they keep their kids out of playgrounds and urge friends to stay distanced at small outdoor picnics, they are continuing the spirit of the past year, when civic duty has been expressed through lonely asceticism. For many people, this kind of behavior is a form of good citizenship. That’s a hard idea to give up.

And so as the rest of vaccinated America begins its summer of bacchanalia, rescheduling long-awaited dinner parties and medium-size weddings, the most hard-core pandemic progressives are left, Cassandra-like, to preach their peers’ folly. Every weekday, Zachary Loeb publishes four “plague poems” on Twitter—little missives about the headlines and how it feels to live through a pandemic. He is personally progressive: He blogs about topics like Trump’s calamitous presidency and the future of climate change. He also studies disaster history. (“I jokingly tell my students that my reputation in the department is as Mr. Doom, but once I have earned my Ph.D., I will officially be Dr. Doom,” he told me.) His Twitter avatar is the plague doctor: a beaked, top-hat-wearing figure who traveled across European towns treating victims of the bubonic plague. Last February, Loeb started stocking up on cans of beans; last March, he left his office, and has not been back since. This April, as the country inched toward half of the population getting a first dose of a vaccine and daily deaths dipped below 1,000, his poems became melancholy. “When you were young, wise old Aesop tried to warn you about this moment,” he wrote, “wherein the plague is the steady tortoise, and we are the overconfident hare.”